What Were the First 10 Items In the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum?

Hint: It started with a purchase from Frederick Stringfellow in 1889.

:focal(361x152:362x153)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/17/fd1730cb-0ac8-4375-8364-48030aabfae4/lilienthal_glider_1.jpg)

Nearly ten million visitors attended Philadelphia’s International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine—more commonly known as the World’s Fair—in 1876. When they eventually made their way through the 60,000 exhibits to the Chinese display, they were treated to teapots and tobacco, fabrics and musical instruments, “hideous masks” and “Chinese kites and balloons in different shapes of strange-looking insects and birds.” At the close of the World’s Fair, 43 of those kites—along with 60 boxcars filled with other items from the exhibition—were donated to the Smithsonian Institution. Much later, 20 of the kites were given to the National Air and Space Museum; they are some of the earliest and oldest items in the collections. (You can read about their conservation, here.)

But they weren’t the first items to enter the collection; in fact, the kites are listed as Accession Lot #223. So what were the first 10? We asked Erik Satrum, supervisory registrar, for help. “The conventional wisdom is that the oldest items in the collection are the Chinese kites from the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition,” he wrote to us in an email. “However, the earliest dedicated aerospace collections listed in the logbooks begin with Lot #1, which was a purchase from Frederick Stringfellow in 1889.”

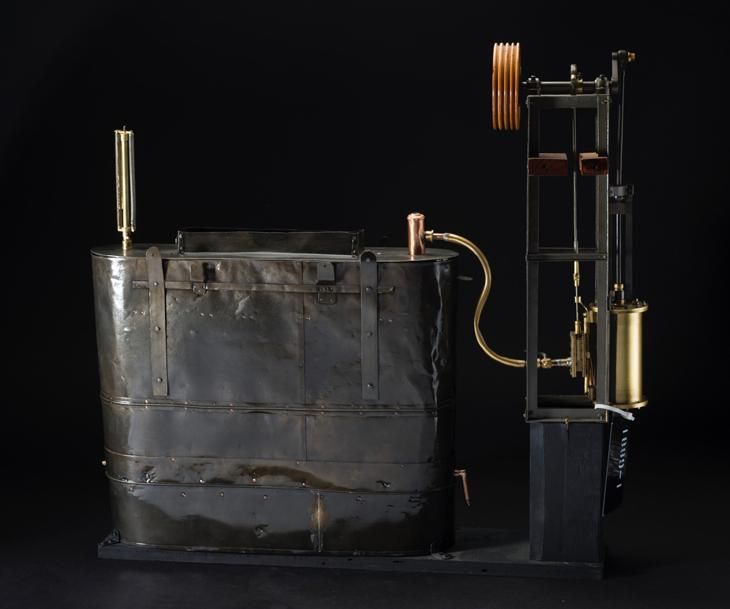

- Included in Lot #1 was the Stringfellow steam engine, shown above; the fuselage of a Stringfellow triplane; and fixed-pitch, two-blade, wood and fabric propellers. While Stringfellow’s inventions failed to perform as he’d hoped, they inspired the public’s imagination for years. His triplane influenced aeronautical designers, including the Wright brothers, to use stacked wings in their aircraft.

- Lot #2 dates from 1890, and includes a toy helicopter acquired from designer Pichancourt in Paris, as well as three mechanical birds given to the Smithsonian by the Government of Nicaragua. A note in the file by curator Paul Garber indicates that by 1929, only a single model was still extant; his belief was that the others were broken during testing by Samuel Langley or otherwise lost.

- Lot #3, dating from 1905, includes Langley Aerodrome No. 5. The Museum’s database notes that on May 6, 1896, No. 5 “made the world’s first successful flight of an unpiloted, engine-driven, heavier-than-air craft of substantial size. It was launched from a spring-actuated catapult mounted on top of a houseboat on the Potomac River near Quantico, Virginia. Two flights were made that afternoon, one of 3,300 feet and a second of 2,300 feet, at a speed of approximately 25 miles per hour.” Two additional artifacts are included in this lot: Langley Aerodrome No. 6, which flew 4,790 feet on November 28, 1896; and the Langley Quarter-scale Aerodrome, below. Langley’s underpowered and unstable full-scale Aerodrome would never be successful, and Langley, who had spent 17 years trying to develop a power-driven airplane, would be crushed by public ridicule. After Langley’s death in 1906, Wilbur Wright wrote to Octave Chanute: “[T]hat the head of the most prominent scientific institution in America believed in the possibility of human flight was one of the influences that led us to undertake the preliminary investigation that preceded our active work. [Langley] recommended to us the books which enabled us to form sane ideas at the outset. It was a helping hand at a critical time and we shall always be grateful…. He deserves more credit [for his work in the field of aeronautics] than he has yet received. I think his treatment by the newspapers and many of his professed friends most shameful.”

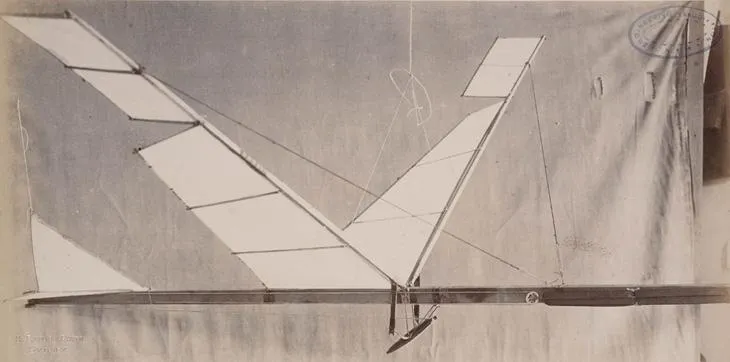

- Lot #4, from 1906, is the Otto Lilienthal glider shown at top. The Wrights would be inspired by the descriptions in Lilienthal’s The Problem of Flying and Practical Experiments in Soaring.

- Lot #5, also from 1906, consisted of a Lawrence Hargrave ornithopter research model dating from 1890. It may have looked similar to the one below. Hargrave’s greatest contribution to aeronautics was the invention of the large box kite, which was essentially a biplane.

- There is no Lot #6; the logbook skips to Lot #7, which includes six items donated by Octave Chanute: An 1895 Chanute model; a Butresof model; three Herring kites, dating 1894, 1896, and 1898; and “parts of flying machine models.” All of these models are listed as “disposed of” in 1913.

- We find the same thing for Lot #8, also donated by Chaunute: An 1897 flying machine model; a cellular kite; and a 12-wing flying machine model from 1894-95. These were also deaccessioned in 1913.

- Lot #9 consists of a Clement V-2 engined used to power Alberto Santos-Dumont’s Airship No. 9 Baladeuse. The engine was acquired in 1908, and is thought to be the smallest motor successfully applied to an airship.

- Lot #10 is a photograph of the Scientific American Flying Machine trophy, dating from 1908. The photograph is not scanned, so we offer you a glimpse at the actual trophy, which is on display in the Museum’s Early Flight Gallery. Why is this trophy important? On July 4, 1908, Glenn Curtiss flew the June Bug across Pleasant Valley for a distance of 5,090 feet, making the first officially recognized, pre-announced, and publicly observed flight in the United States. This effort would establish Curtiss as America’s foremost aviator.

- Lot #11, acquired in 1908, is the Langley-Manly-Balzer Radial 5 engine, the first internal combustion engine specifically designed for an aircraft. It was commissioned by Samuel Langley; the engine, an 1899 air-cooled rotary designed and built by Stephen M. Balzer of New York, was redesigned as a water-cooled radial by Charles M. Manly, Langley’s assistant.

“I would not be surprised if there were a few items in the current collection that pre-date the Chinese kites and the Stringfellow engine,” writes Satrum. For instance, the Museum “is also in possession of several artillery rockets from the 1800s including a Congreve 100-pounder war rocket made by Sir William Congreve in 1815, and a Hale 24-pounder war rocket from 1863 [Lot #1816]. Both were presented to the Museum by the Royal Artillery Institute in 1968, along with a group of five additional Hale rockets, and one 24-pounder Boxer rocket from the mid-1800s that were transferred to the Museum by the Royal Arsenal in 1979 [Lot #6301].”