207 Flights, Hundreds of Holes

The conservation of a record-setting B-26 bomber will preserve every battle scar.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/90/63902e24-d019-4e3e-93c2-9083995105af/16f_am2015_nasm2014-06705_live.jpg)

The Martin B-26 Marauder Flak-Bait survived two years of the most intense aerial combat of World War II, taking every punch German gunners and fighter pilots threw at it. Though bullets and shell fragments riddled the aircraft, ground crews repeatedly put the B-26 back in the air. By V-E Day, Flak-Bait had racked up more missions than any other U.S. aircraft.

The ship returned Stateside in crates, and spent decades scattered through the recesses of the National Air and Space Museum’s storage facility outside Washington, D.C. In 1976, Flak-Bait’s nose and cockpit emerged to become a highlight of the World War II gallery in the Museum on the National Mall. Now, some seven decades after service in World War II, the iconic bomber is being made whole by Museum conservators and restoration experts.

Flak-Bait represents the fleet of 5,157 B-26 medium bombers produced by the Glenn L. Martin Company from 1940 through 1945. Martin designer Peyton Magruder’s powerful, twin-engine design won a 1939 Army Air Corps competition for a fast machine capable of carrying 4,000 pounds of bombs at more than 300 mph over a range of 2,000 miles. With conflicts emerging in Asia and Europe, the Air Corps wanted the new B-26 badly enough that it skipped the prototype stage and ordered 201 Marauders before the first one rolled off the production line.

Jeremy Kinney, the Museum curator responsible for Flak-Bait, says the B-26 pioneered a number of advances later employed widely in U.S. combat aircraft, including self-sealing fuel tanks, a power-operated gun turret, and a low-drag, high-speed wing. “Martin pushed the state of the art in aircraft manufacturing,” says Kinney, “introducing the first all-plastic aircraft nose, heat treatment of aluminum sheets, and a method of projecting part dimensions directly onto photo-sensitive aluminum stock to ensure accurate cuts.”

The first flight was made in November 1940; just three months later the Marauder was on its way to the 22nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field in Virginia. But in the rush to get the aircraft into service, a number of serious problems emerged: Nosegear struts broke under heavy takeoff or landing loads, and leaky hydraulics led to a rash of gear failures. Had the aircraft undergone more extended testing, these might have been dealt with before widespread operations began.

Most worrisome was that the young pilots pouring out of flight schools in 1941 and ’42 were ill-equipped to handle the B-26’s high approach and landing speeds. Unseasoned pilots had surprises: Get slower than 145 mph on final and the Marauder would stall. Lose an engine on takeoff or in a traffic-pattern turn and the bomber would roll and plunge earthward.

By 1943, Martin addressed the B-26’s approach and single-engine handling challenges: The company lengthened the wing from 65 to 71 feet, and stretched the vertical stabilizer’s height by nearly two feet to increase rudder control.

An intensive training program initiated by General Jimmy Doolittle, and implemented largely by his aide, Major Vincent “Squeek” Burnett, raised pilot skills.

In the grim months after Pearl Harbor, though, Marauder crews went to war with what they had. They attempted to hit the Japanese fleet at Midway, and in the southwest Pacific attacked Rabaul from bases in New Guinea. Soon after, the B-26 fought against Rommel’s forces in the North African campaign. In Europe, its initial low-level attacks against German coastal targets proved disastrous. On a May 17, 1943 raid against a power station in Ijmuiden, Holland, lethally accurate anti-aircraft fire and Luftwaffe fighters downed all 10 Marauders that reached the target, killing 34 airmen.

The Marauder fleet’s combat destiny thus hung in the balance when Martin B-26B-25-MA, serial no. 41-31773, rolled off the assembly line at Martin’s Plant 2 in Middle River, Maryland, just northeast of Baltimore, on April 26, 1943.

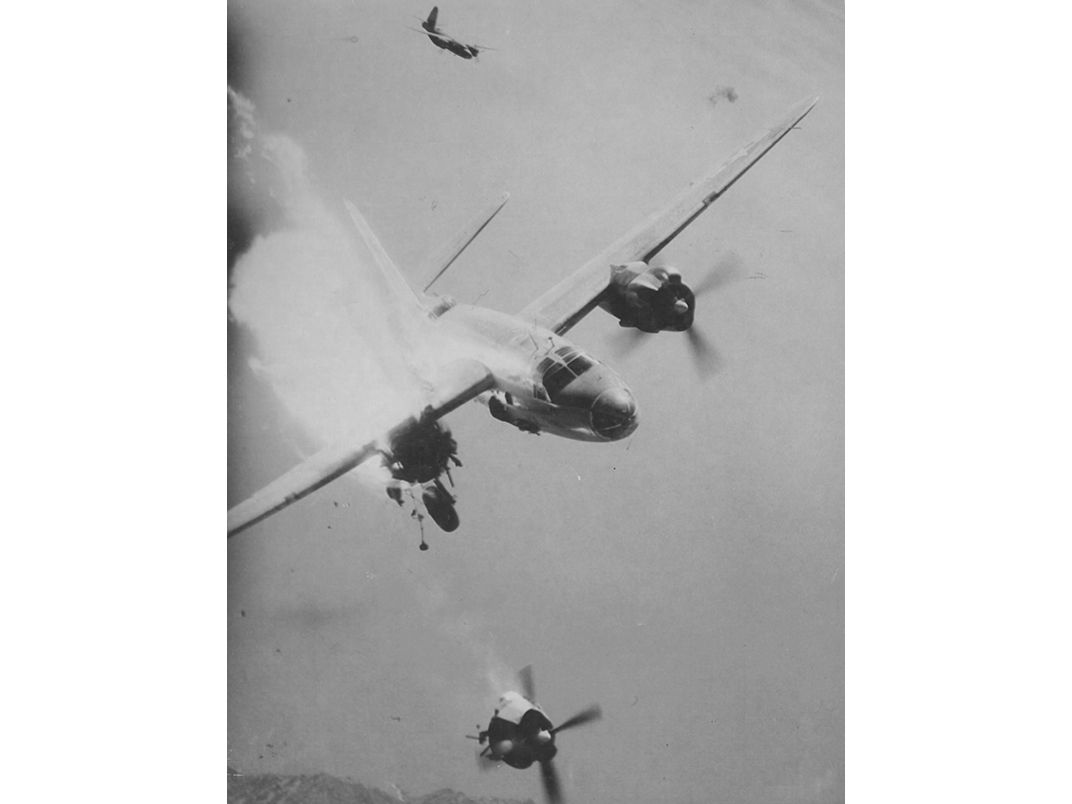

When 773 and its crew arrived in England in late May 1943 to join the 449th Bombardment Squadron of the 322nd Bombardment Group, the shocking losses at Ijmuiden had forced a reevaluation of B-26 tactics. Eighth Air Force commander General Ira C. Eaker ordered the 322nd and other arriving B-26 groups to employ the airplane’s strengths: speed, firepower, and ruggedness. Hereafter, Marauders would deliver their bombs in tight formation and from 8,000 to 12,000 feet, instead of from 100 feet. On July 16, B-26s escorted by Spitfires struck the Luftwaffe airfield at Abbeville, France, and didn’t lose a single airplane.

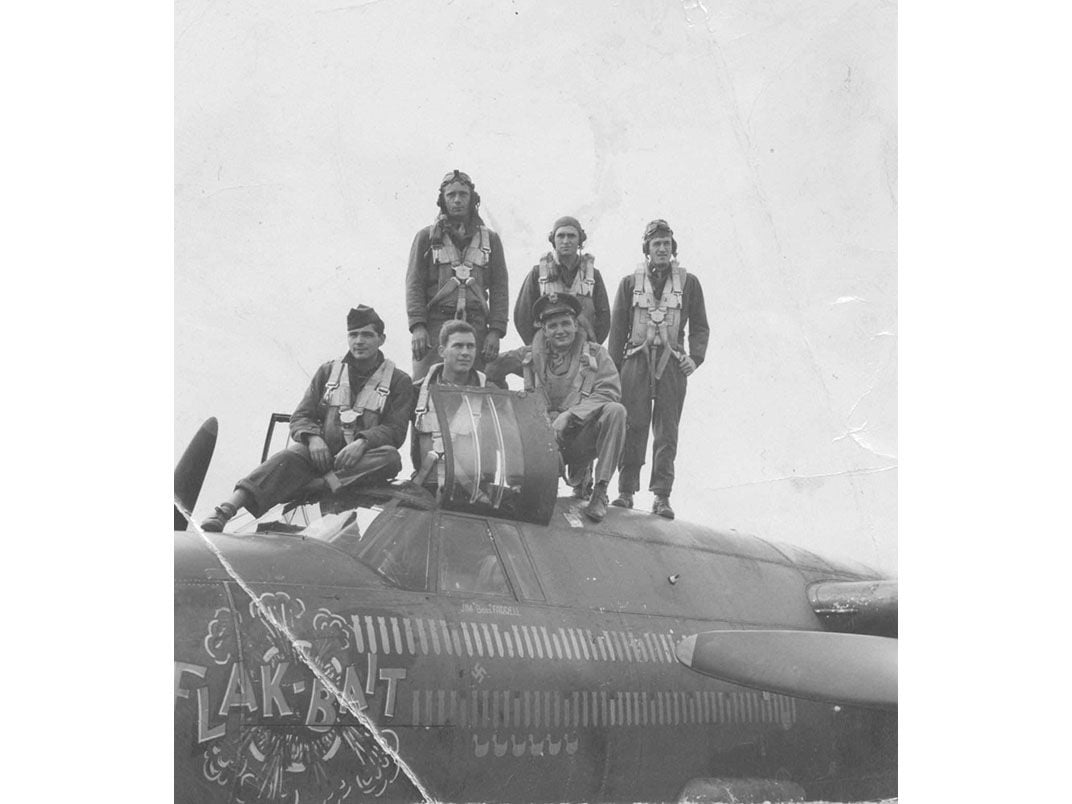

B-26 773 was flown that summer by Lieutenant James J. Farrell and his five-man crew: copilot, bombardier, radio operator/gunner, waist gunner, and tail gunner. Seeking a worthy appellation for their new Marauder, Farrell remembered his brother’s nickname for his dog: Flea Bait. In light of their B-26’s seeming appetite for German anti-aircraft bursts, the men thought Flak-Bait sounded just the right devil-may-care note.

Farrell and his crew flew 70 of Flak-Bait’s first 130 missions, mostly in six-ship formations as part of 54-airplane attacks against airfields, marshalling yards, bridges, highway junctions, supply depots, and coastal guns. On 180-mph bomb runs, the squadron’s lead bombardier would pinpoint the target with his Norden bombsight, the pilot following the Norden-driven pilot director indicator, or PDI, on his instrument panel. When they saw the lead ship’s bombs fall, the entire squadron would release their bombs. Each bomber’s 4,000-pound load, usually 500- or thousand-pounders, would contribute to a tight cluster of hits on and around the target.

That was the theory, but in practice, the Germans threw flak and fighters up to disrupt the Marauders’ aim and exact a deadly toll. The B-26 crews were well within the lethal range of high-velocity 88mm guns, each of which could fire 15 to 20 twenty-pound shells per minute, each shell capable of destroying a bomber. Nearing their target, Flak-Bait’s crews were often forced to penetrate storms of flak bursts.

To avoid the 88s, pilots could take evasive action during all but the last few seconds of the bomb run. Said Flak-Bait’s Farrell in a 1978 interview in Airpower magazine, “We figured it took the flak gunners 17 seconds to target us, and another 13 before the shells started bursting. For that reason, we wouldn’t go 30 seconds without doing something—climbing and turning to the right, descending and turning to the left, etc.”

That helped, but for the final 20 or 30 seconds of the run, the pilots had to fly straight and level, centering the needle on the PDI. Here the B-26 was most vulnerable. Stan Walsh was a bombardier with the 397th Bombardment Group on Christmas Day in 1944, at the height of the Battle of the Bulge. On the bomb run, his ship was tucked in just below and behind the lead Marauder when “there was a flash of fire and Lead disappeared. As he fell down and back toward us, we were nearly hit on the vertical fin. We dove out of formation with a perforated tail; the pilot barely recovered using elevator trim alone.”

Flak-Bait began to live up to its name. On almost every mission, it took a hit from 88mm shrapnel.

Every control surface was replaced at least once. The hydraulics were shot out once, the electrical system twice. It came home single-engine twice, once with the dead engine on fire.

Although most of the damage was inflicted by the heavy German guns, B-26 crews also faced Luftwaffe fighters. “We had so many encounters with them early in the war, and my feeling is we became too tough for them. We were knocking down more of them than they were of us,” said Farrell in 1978. The Americans were getting tougher, but at the same time the Luftwaffe was getting weaker. Most fighters had been withdrawn for use in countering the heavy bomber assaults on the Nazi homeland and were seldom seen over occupied France. When Flak-Bait did encounter enemy fighters, the crew had the advantage of as many as 11 Browning .50-caliber machine guns.

On September 6, 1943, Flak-Bait was part of an attack on rail marshalling yards near Amiens, France, when Farrell’s formation was hit by a swarm of Messerschmitt Bf 109s in a head-on attack. A 20mm cannon round tore through the clear nose and exploded on the front of Farrell’s instrument panel, Plexiglas shards and shell fragments wounding him in the leg and hitting bombardier Owen J. “Red” Redmond front and back. Miraculously, Redmond, clad in heavy leather flying gear, was only slightly hurt.

Farrell, with only an airspeed indicator still functional, nursed the B-26 back to the base at Braintree in England.

Farrell’s crew took Flak-Bait up the morning of June 6, 1944. “D-Day was a rainy, rotten day, and we went out about four-thirty in the morning. We got up to high altitude, and even though it was June, there was a lot of ice. There was a miserable cold wave that came through there…. We had the whole group and I was a squadron leader.”

Only a half-dozen Marauders made it up through the thick weather to the rendezvous. Farrell hung in for a couple of long, nerve-wracking bomb runs. “Finally we dropped our bombs and went home. From there on, the weather was a lot better…. The second raid we went on that day was clear. You could see the beach, ships all over. I saw one German fighter that made the run down the beach, saw the run being made and saw the fire going at him.”

Sherman Best logged a year in combat as a B-26 pilot and flew 14 missions on Flak-Bait. He remembers that “the Marauder was a good plane to fly, but it required your full-time attention, but as time went by, I grew to love that airplane—it was very well-built and could take a lot of battle damage.”

Farrell’s crew rotated home in July 1944, and others took Flak-Bait through the Normandy breakout and deep into Germany. On April 17, 1945, nearly two years after her birth in Middle River, Flak-Bait notched her 200th combat mission, topping other U.S. bombers.

The war in Europe ended with Flak-Bait’s mission total at 207; the B-26 fleet was retired in favor of the Douglas A-26 Invader. At two locations in Germany, depot workers dynamited the remaining Marauders into scrap aluminum. That sad end saved the expense of flying obsolescent aircraft home and helped revive the industrial economies of war-torn Europe. To Marauder crews, however, it was a cruel, undeserved insult to their aircraft’s proud service.

Flak-Bait was spared this fate: Because of its 200 missions, which included two missions on D-Day and 21 missions against V-1 flying-bomb sites in France, General of the Army Henry “Hap” Arnold selected the aircraft to include in a collection of distinctive examples of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ war-winning combat aircraft set aside for the National Aeronautical Collection. On March 18, 1946, Major John Egan and Captain Norman Schloesser flew Flak-Bait one last time, to an air depot at Oberpfaffenhofen in Bavaria. There the famed bomber was disassembled, crated, and shipped to a Douglas factory in Park Ridge, Illinois.

In 1960, National Air Museum director Paul Garber moved the crated Flak-Bait to the Museum’s Silver Hill, Maryland warehouse complex. Only the cockpit section made it into the Museum on the Mall in 1976.

Last August, the Museum’s restoration team began the process of resurrecting the bomber. They shifted Flak-Bait’s nose, bomb bay, and tail sections, along with dozens of major components and crate after crate of smaller parts, to the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. The team has assessed the airplane’s condition, and treatment has begun.

Says Kinney, “It’s the originality of the artifact that’s so striking. What’s amazing is that the aircraft is pretty much as it was in 1945. It shows dust, scratches, and lumps, but it’s the ‘barn find’ of our dreams.”

Even in pieces, Flak-Bait inspires awe. The ship’s battle scars are revealed by dozens, if not hundreds, of riveted aluminum and fabric patches, daubed with olive drab and apple-green zinc chromate. “There are two patched holes in the wings in excess of 16 inches wide,” says Pat Robinson, one of several restorers assigned full-time to Flak-Bait. On the landing gear door are penciled dozens of signatures of the airmen who disassembled the ship at Oberpfaffenhofen. The engine oil coolers were still full of oil from the final flight. Hydraulic lines drip red fluid, seemingly fresh enough for another combat sortie.

Inside the fuselage, conservators found spent .50-caliber shell casings, live rounds, cigarette butts, wooden matches, and handfuls of “Window,” or chaff, fine aluminum strips used to evade enemy gun-laying radar. The team continues to find bits of German flak embedded in the wings and structure.

“We want to stabilize and preserve,” says Kinney, “rather than replace and restore.” The team wants visitors to see Flak-Bait not factory-fresh but as she was at war’s end, with the battered paint and patched bullet holes recording her service.

Pat Robinson is clear-eyed about the challenges of working with “an absolute time capsule.” Control surface fabric is falling apart. Rubber seals and wire insulation are crumbling. Corrosion has attacked magnesium parts built for a couple of years of frontline service, not 70 years in storage. “There are some tough choices to make,” Robinson says. “We can’t save everything on the airplane.”

Robinson is clinical when talking about the work ahead, but the airplane has its effect on even him. “Yes, it’s a piece of metal. But the Martin men and women in Baltimore built that airplane when the war’s outcome was very much in doubt. They put their hearts into it. It was over Utah Beach twice on D-Day. What did those crews feel and think about when they took Flak-Bait into battle? This is a once-in-a-lifetime project.”

To Kinney, Flak-Bait is “a central artifact of our collection of World War II aircraft, one so important to preserve and display. One glowing indicator of the public interest in Flak-Bait is the paint that’s been worn off the nose and bomb bay bulkhead by visitors, who wanted to ‘touch history.’ ”

In a larger sense, says Kinney,

“Flak-Bait is an example of the weapons Americans needed to win World War II—building the M1 rifle, the Sherman tank, the LST [landing ship, tank], and the B-26 by the thousands. Here is a plane that dozens of Americans flew to war, and to victory.”