America’s Oldest Sweet Shop Gets a Hipster Makeover

How Philadelphia candymakers Eric and Ryan Berley are giving new life to Shane Confectionery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Candy-Store-Eric-and-Ryan-Berley-631.jpg)

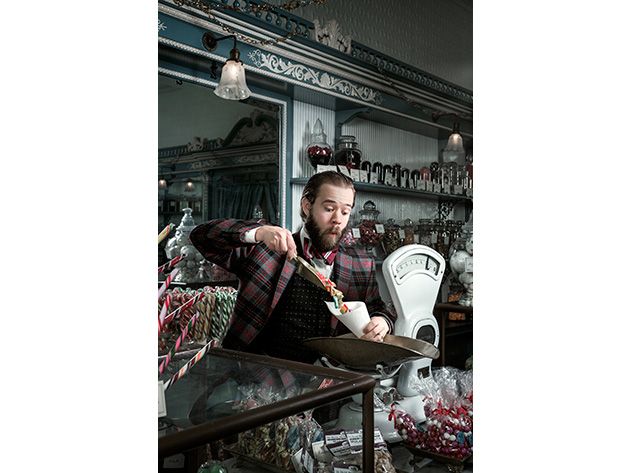

Grinning the widest of grins and sporting the snuggest of suspenders, Ryan Berley shimmies past the carved hardwood display cases at Shane Confectionery like a kid in a candy store. A 36-year-old kid, but a kid nonetheless. He’s entitled: It’s his candy store.

Berley and his 32-year-old brother, Eric, recently bought and restored Shane’s, the oldest continuously operated candy shop in America. The Philadelphia landmark, a couple of blocks from where in 1732 Benjamin Franklin printed the first Poor Richard’s Almanack, has been turning out sweets since 1863.

The first candy men at the spot, Samuel Herring and Daniel Dengler, were primarily wholesalers. A canned-fruit broker named Edward R. Shane took the business retail in 1911, and for three generations the staff boiled, stretched and sculpted blobs of sugary goo into every imaginable shape and Technicolor hue.

Shane’s reputation rested largely on its buttercream eggs and Irish potatoes—triumphs of Willy Wonka-ish alchemy that were neither Irish nor potatoes, but lumps of cream cheese mixed with coconut and dusted with cinnamon. To make the “eyes” of these spuds trompe l’oeil, confectioners poked the morsels with three-pronged forks and inserted pine nuts in the holes.

Originally, Shane’s fed off the foot traffic of commuters ferried between Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey. The traffic slowed to a toddle in 1926 with the opening of the Delaware River Bridge, later renamed for Ben Franklin. World War II sugar shortages and late 20th-century urban blight also swallowed up profits. By 2010 the third-floor workshop was in disarray, the antique machinery in disrepair, the chocolate empire nearing, well...meltdown.

Enter the Berleys, proprietors of the Franklin Fountain, a vintage ice-cream parlor a few doors down Market Street. The brothers bought in, boned up on the store’s history and embarked on a painstaking restoration. They ripped up the linoleum flooring to expose the original pine and bird’s-eye maple and repainted the woodwork in Long Gallery and Grand Staircase blue, shades nicked from the palette at Independence Hall.

Nowadays the shelves boast hundreds of classic and seasonal delights, about half of which are concocted in the upstairs candy lofts. A cabinet is jammed with red and green and amber “clear toys,” edible Pennsylvania German delicacies made of sugar and corn syrup that glint like carved ice. The Berleys have some 1,200 cast-iron clear toy molds, everything from steam engines to Scottish terriers. Their singular contribution to Candyland is the Whirly Berley Bar, a salted-caramel and chocolate dainty described by one of the shop’s owners as “sweet, complex and savory, just like a Berley brother.”