Sully’s Tale

Chesley Sullenberger talks about That Day, his advice for young pilots, and hitting the ditch button (or not)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sullenberger-flash.jpg)

Long before he won instant celebrity for his cool handling of the ditching of US Airways flight 1549 in the Hudson River on January 15, 2009, Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger had thought a lot about airline safety procedures. But when it came time to apply those lessons, he and his crew relied as much on instinct as on the playbook. Sullenberger spoke with Air & Space editor Linda Shiner on February 16, almost a month to the day after the dramatic events that earned him worldwide acclaim from fellow pilots and the public alike.

Air & Space: I heard you say in one of your interviews that it was comforting to you to hear the flight attendants, after you announced “Brace for impact,” also directing the passengers to brace and put their heads down. Why was that a source of comfort?

Sullenberger: I felt they were assisting me in that moment. Even though we were intensely focused and very busy, I remember thinking that as soon as I made the public address announcement in the cabin, within a second or two, I heard even through the hardened cockpit door the flight attendants in unison shouting their commands. “Heads down. Stay down.” And it was comforting to me to know that they were on the same page, that we were all acting in concert. It made me feel that my hope and my confidence in completing this plan was reasonable and that they knew what needed to be done and were doing their part.

Air & Space: Is it standard procedure for the captain to go back through the cabin after an emergency like yours?

Sullenberger: I felt that as more of a personal responsibility than a procedural responsibility—which it may be. But I had the time, the aircraft was stable, and I was not concerned that it would suddenly sink. And so I could leave absolutely no possibility of anyone being left behind. I made a thorough search, calling out, “Is anyone there?” to make sure the evacuation was complete, and it was.

Air & Space: You made the decision to ditch within one minute of losing power in the engines. Is that correct?

Sullenberger: You may know better than I. I have not seen an official timeline, or official data of any kind from the investigators. All I have seen is what’s been reported in the press—based upon the daily press briefings given by the NTSB [National Transportation Safety Board] during the initial phase. I knew it had to be done quickly.

Air & Space: Before you made that decision, you’d briefly considered returning to LaGuardia. You’d considered diverting to Teterboro [New Jersey]. Was there a discussion between you and your first officer about the distances you could glide or the amount of energy you might sacrifice if you had to head to either of those airports?

Sullenberger: I haven’t listened to the cockpit voice recorder yet. At some point before the NTSB public hearing in a few months, I will have to do that. Until then, I’m not sure. I would characterize the cockpit as being busy, businesslike, and our cooperation was done largely by observing the other and not communicating directly because of the extreme time pressure. [First officer] Jeff [Skiles] and I worked together seamlessly and very efficiently, very quickly, without directly verbalizing a lot of issues. We were observing the same things, we had the same perceptions, and it was clear to me that he was hearing what I was saying to Air Traffic Control on the radio. He was observing my actions, and I was observing his, and it was immediately obvious to me that his understanding of the situation was the same as mine, and that he was quickly and efficiently taking the steps to do his part.

Air & Space: What is the role of the first officer in that situation?

Sullenberger: This was not a typical case. Because of the extraordinarily difficult nature of the situation and because of the extreme time pressure, we both had to take on different roles than what typically would be done according to protocol. Most of the training that we get is for a situation where you have more time to deal with things. You have time to be more thoughtful, to analyze the situation. Typically what’s done these days is for the first officer to be the pilot flying and for the captain to be the pilot monitoring, analyzing and managing the situation. There wasn’t time for that.

I felt that even though Jeff was very experienced—he turns out to have had as much total flying experience as I do—and even though he’d been a captain before on another airplane at my airline and had been at the company 23 years, he was relatively new on this particular aircraft type [Airbus A320]. In fact, this was his first trip after having completed training on it. He’d been through the simulator and the ground school and had been on a four-day trip with an instructor, but this was his first trip to fly. So I decided early on that we were best served by me using my greater experience in the [A320] to fly the airplane.

Additionally, I felt like I had a clear view out the left-hand and forward windows of all the important landmarks that I needed to consider. They were on my side. They would be easier for me to see. And ultimately the choice of where we would go and what flight path we would take would be mine.

I also thought that since it had been almost a year since I had been through our annual pilot recurrent training, and Jeff had just completed it—he had just been in the simulator using all the emergency checklists—he was probably better suited to quickly knowing exactly which checklist would be most appropriate, and quickly finding it in this big mutlipage quick reference handbook that we carry in the cockpit. So I felt it was like the best of both worlds. I could use my experience, I could look out the window and make a decision about where we were going to go, while he was continuing his effort to restart the engines and hoping that we wouldn’t have to land some place other than a runway. He was valiantly trying until the last moment to get the engines started again.

Air & Space: Were you calculating the distance you could glide?

Sullenberger: It wasn’t so much calculating as it was being acutely aware, based upon our energy state and by visually assessing the situation, of what was and what was not possible. There are several ways I used my experience to do that. I knew the altitude and airspeed were relatively low, so our total energy available was not great. I also knew we were headed away from LaGuardia, and I knew that to return to LaGuardia I would have to take into account the distance and the altitude necessary to make the turn back.

In the case of Teterboro, I knew that was even farther away, even though we were headed in that direction. The short answer is, based on my experience and looking out the window, I could tell by the altitude and the descent rate that neither [airport] was a viable option. I also thought that I could not afford to choose wrongly. I could not afford to attempt to make it to a runway that in fact I could not make. Landing short, even by a little bit, can have catastrophic consequences not only for everybody on the airplane but for people on the ground.

Air & Space: What was your speed when you lost the engines?

Sullenberger: Again, I would hate to guess. I have not seen the data. It was less than 250 knots the entire time. And I think once the thrust loss occurred, our speed began to decay very rapidly because the nose was still up in a climb attitude, but without climb thrust on the airplane. It required a substantial but smooth push to get the nose down to attain and maintain our best lift-over-drag airspeed.

Air & Space: So that was your first move: to get the nose down.

Sullenberger: Yes.

Air & Space: When you’re in this situation are you just trying to make it go as far as you can?

Sullenberger: My initial focus was to fly at the proper speed while we were assessing the situation. We needed our best lift-over-drag airspeed while we were trying to decide where we could go. Once we had considered and ruled out both LaGuardia and Teterboro as unattainable, then we flew that same speed down to a lower altitude where we began to slow so that we could put out flaps for landing.

Air & Space: How did you slow down? Were you using control surfaces?

Sullenberger: No. We slowed by raising the nose. Our descent rate was more rapid than usual because we had essentially no thrust. So in order to maintain a safe flying speed, we had to have the nose far enough down that we could hold that speed as we descended. Of course that resulted in a higher-than-normal rate of descent.

Air & Space: Did you flash back on any of your experiences as a glider pilot? Did it feel natural to you?

Sullenberger: Actually not very much after the bird strike felt very natural, but the glide was comfortable. Once we had established our plan, once we knew our only viable option was to land in the river, we knew we could make the landing. But a lot of things yet had to go right.

I get asked that question about my gliding experience a lot, but that was so long ago, and those [gliders] are so different from a modern jet airliner, I think the transfer [of experience] was not large. There are more recent experiences I’ve had that played a greater role.

One of the big differences in flying heavy jets versus flying lighter, smaller aircraft is energy management—always knowing at any part of the flight what the most desirable flight path is, then trying to attain that in an elegant way with the minimum thrust, so that you never are too high or too low or too fast or too slow. I’ve always paid attention to that, and I think that more than anything else helped me.

I also participated as an Air Line Pilots Association safety volunteer on the NTSB teams that investigated two of the airline’s previous accidents: the San Luis Obispo PSA 1771 crash in 1987 and the later Los Angeles runway collision in the early nineties.

The way I describe this whole experience—and I haven’t had time to reflect on it sufficiently—is that everything I had done in my career had in some way been a preparation for that moment. There were probably some things that were more important than others or that applied more directly. But I felt like everything I’d done in some way contributed to the outcome—of course along with [the actions of] my first officer and the flight attendant crew, the cooperative behavior of the passengers during the evacuation, and the prompt and efficient response of the first responders in New York.

Air & Space: When the birds struck, the engines stopped operating, is that correct? They weren’t at idle power; they were at nothing?

Sullenberger: Again, I have not seen the data. They certainly were not capable of producing usable thrust.

Air & Space: In trying to relight the engines, could the computer have misread the situation and kept the engines from producing the thrust you needed to recover?

Sullenberger: I would not want to speculate on that, and that would be all I could do at this point. I have not seen the data from the recorders. As far as I’m concerned, it was clear to Jeff and myself that neither engine was producing thrust.

Air & Space: Had you trained for dead stick landings as an airline pilot?

Sullenberger: That’s never been part of our annual recurrent training. I do remember on a number of occasions attempting in the simulator under visual conditions—not a water landing, but an attempt to make a runway. We would be set up on a nearby heading where we could see the airport, and we knew that it was at a place and an altitude where it was possible to get to the runway. That was the one thing I remember practicing some years ago.

Air & Space: Does the Airbus operator’s manual have a procedure for ditching?

Sullenberger: Yes.

Air & Space: So your first officer would have found that procedure and had a checklist to go through for the ditching procedure?

Sullenberger: Not in this case. Time would not allow it. The higher priority procedure to follow was for the loss of both engines. The ditching would have been far secondary to that. Not only did we not have time to go through a ditching checklist, we didn’t have time to even finish the checklist for loss of thrust in both engines. That was a three-page checklist, and we didn’t even have time to finish the first page. That’s how time-compressed this was.

Air & Space: Did the airplane have a ditch button that would have sealed certain openings in the cabin?

Sullenberger: Yes, it’s called a ditching push button. And there was not time. We never got to the ditching push button on the checklist. It wouldn’t have mattered anyway. The vents that are normally open are small. And once the airplane touched the water, the contact opened holes in the bottom of the airplane much, much larger than all of the vents that this ditching push button was designed to close.

I cannot conceive of any ditching or water landing where it would help. Theoretically I understand why the engineers included it. It sounded like a good idea, but not in practice. We had a successful water landing, and even then, from seeing pictures of [the airplane] being removed from the river by a crane, there were much larger holes than the vents this button was designed to close.

Air & Space: Do you still love to fly?

Sullenberger: Oh, yeah. It’s been a passion since I was 5. I can remember at 5 years old knowing that I was going to fly airplanes. And I was just fortunate enough at every juncture to be able to get to the next goal. I’m not sure what I would have done had I not been able to fly. I never even considered anything else.

Air & Space: What's the best landing you've made?

Sullenberger: A time I'd flown into San Francisco, on an evening when air traffic wasn't particularly heavy and the air traffic controllers do not have to impose upon you a lot of constraints. It was a pretty night and I could see the airport from far away, and I tried to make as smooth and elegant a continuous descent as I could. You could barely feel the wheels touch.

Air & Space: Any advice for aspiring pilots?

Sullenberger: Well, not just for aviators, but for all of us. My view of the world is that people are best served when they find their passion early on, because we tend to be good at things we’re passionate about. I think we also need to find people whom we admire and try to emulate them

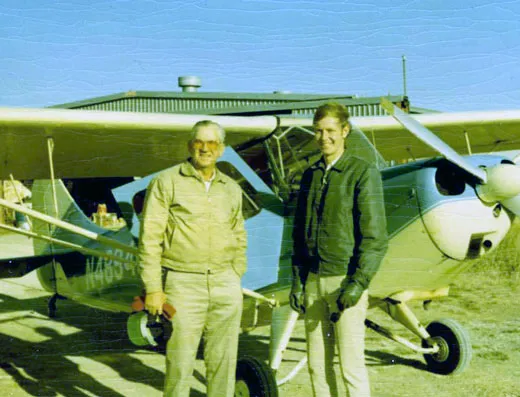

Air & Space: And who did you admire?

Sullenberger: My first flight instructor, L.T. Cook Jr., was a Civilian Pilot Training Program instructor during World War II, a real gentleman and a stick-and-rudder man. He was a cropduster and had his own grass strip in rural Texas. In 1967, I paid $6 an hour for the airplane and gas and $3 an hour for his time. Among the thousands of cards I received [after the ditching], I discovered one from his widow. She wrote, "L.T. wouldn't be surprised, but he certainly would be pleased and proud."