Israel’s First Air Force

A new book documents the rise of a formidable fighting force.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/0c/fc0c98b9-fc6d-47a8-9f69-1402cce638a3/avia-s-199_ezer_weizman.jpg)

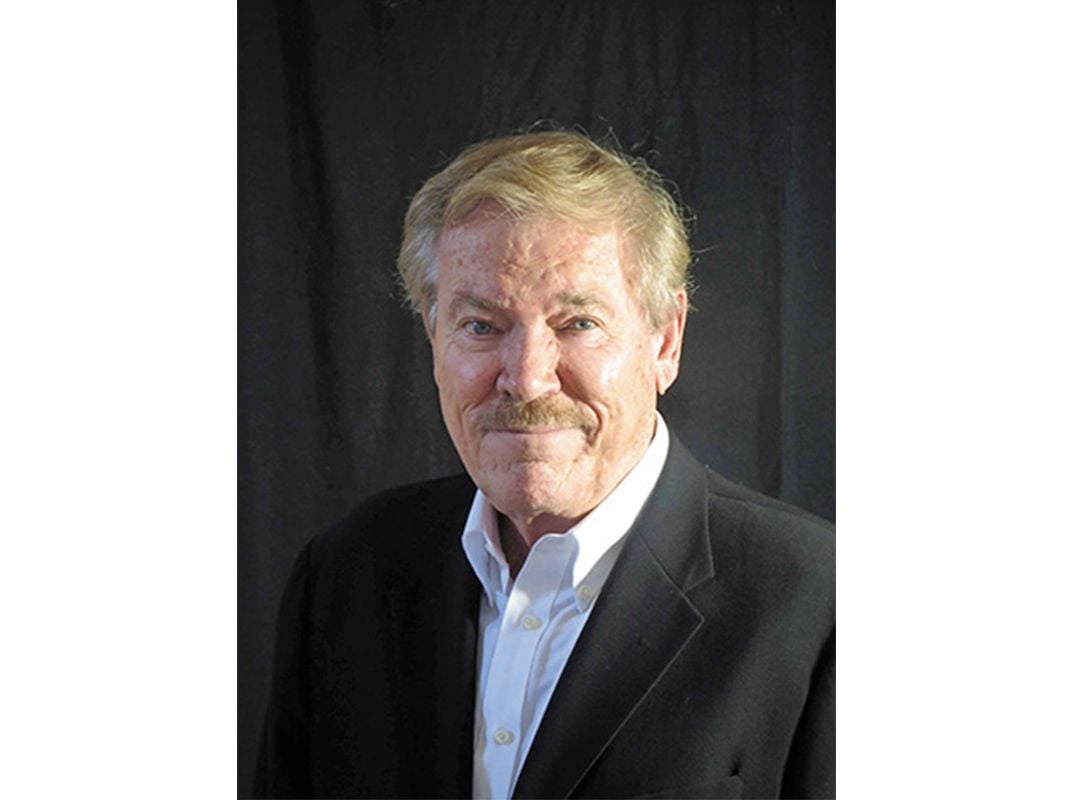

In his latest book, Angels in the Sky: How a Band of Volunteer Airmen Saved the New State of Israel, Robert Gandt examines how an enterprising group of volunteer pilots flying a ragtag fleet of aircraft (Bristol Beaufighters, C-46s, B-17s, Spitfires) helped turn the tide during Israel’s 1948 struggle for independence.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Gandt: After 16 books of fiction and aviation history, I’ve learned to spot a great story when I hear it. This one came to me a few years ago when I was introduced to a 92-year-old ex-U. S. Navy fighter pilot named Mitchell Flint. As he was telling me about his actions in the 1948 war in Israel, describing what it was like to fly a Messerschmitt fighter and dive-bombing with an AT-6, the thought struck me like a thunderbolt: This was a book I had to write. I knew I was hearing the quintessential David vs. Goliath tale with all the classic ingredients: a see-saw battle for survival, a high-stakes plot with the outcome in doubt until the very end, and an international cast of colorful heroes. From that day on, I was committed.

What did you discover about the volunteer airmen who rescued Israel that wasn’t widely known before?

That they were not all cut from the same mold. Though most were World War II veterans, each had his own story and reason for going back into combat only three years after the war. Many of the Jewish volunteers had lost relatives in the death camps of Europe, and for them, saving Israel from another Holocaust was a sacred duty. But nearly a third of the airmen were not Jewish, and their motivations were varied. Some were idealists who saw the war as a noble cause. For them it was simply the right thing to do. A number of others were adventurers for whom World War II had been the peak experience of their lives. The war in Israel provided everything they missed: the thrill of combat, the comradeship of fellow warriors, a mission for which they didn’t mind risking their lives. In that sense, the airmen who went to Israel were akin to the volunteers in earlier wars: the Lafayette Escadrille, the Flying Tigers, the Eagle Squadron of the Royal Air Force.

Were all of the airmen volunteers?

They were all volunteers, but some of the later arrivals, particularly fighter pilots with high combat experience, were recruited with the promise of attractive salaries. It was a subject that rankled some of the early volunteers who had signed up for minimal—or in some cases zero—compensation. For their part, the hired guns mostly kept quiet about how much they were paid, and joined the battle with as much passion as the idealists. Several stayed in Israel for a while after the war to help train the new all-Israeli air force. In later years, the distinctions between the volunteers faded away, and they became lifelong brothers in what they would all remember as a righteous cause.

Was the air portion of Israel’s war of independence a logistical nightmare? How did the young Israeli air force assemble its fleet of aircraft?

The U.S. Neutrality Act of 1939 forbade the shipment of arms or war surplus aircraft from the U.S. to Israel. Britain imposed its own arms embargo as well as a naval blockade on shipments to Israel while at the same time supplying weapons and modern warplanes to the Arab nations threatening Israel. But in the U.S., an ingenious former TWA flight engineer named Al Schwimmer was quietly rounding up a gaggle of war surplus aircraft, managing to stay just one step ahead of FBI and Customs agents. In a succession of daring getaways, volunteer airmen slipped out of the country with Schwimmer’s stash of airplanes, including 10 C‑46s, a Constellation airliner, and three B-17 bombers. The C-46s became Israel’s main supply lifeline.

The Haganah—the underground militia that would become the Israeli Defense Force—was playing similar cat-and-mouse games in Britain. An agent named Emmanuel Zur managed to acquire four war-surplus Bristol Beaufighter attack aircraft, but he was blocked from taking them out of the country. Zur came up with a creative solution: He created a bogus movie production company for the purpose of making a film about a World War II squadron. While the cameras rolled, a crowd gathered, including suspicious inspectors from the Ministry of Civil Aviation. Zur’s four Beaufighters took off. But instead of roaring back over the movie set according to the script, the Beaufighters turned south. And disappeared. Not until the next day did the inspectors learn the truth: The Beaufighters were in Israel.

But the warbirds that Israel most desperately needed—fighters like the P-47 Thunderbolt or P‑51 Mustang—were still out of Schwimmer’s reach. Unable to obtain fighters from the U.S., Israel turned to a source behind the Iron Curtain. Czechoslovakia was willing to sell 25 Avia S-199s—the Czech-built version of the Messerschmitt Bf 109. The Czech Messerschmitts were treacherous airplanes to fly, but with the war already beginning, the fledgling air force had no other options. Several months later, Israel acquired superior fighters—British-built Spitfires from Czechoslovakia, and a pair of P-51 Mustangs Schwimmer had smuggled from the U.S. in crates labeled “agricultural equipment.”

Was it difficult to maintain the aircraft and find replacement parts?

The young IAF mechanics, many of them American and British World War II veterans, became masterful at scrounging pieces from scrapped machines, fabricating new parts, and stealing from supply depots overseas. They had to perform miracles to keep the Messerschmitts in the air. Nearly every one of the clunky fighters was involved in a takeoff or landing mishap, wiping out the landing gear or flipping upside down and trapping the pilot inside. Just as important, was the job of keeping the lumbering C-46 Curtiss Commandos airborne. The big twin-engine transports were flying 14-hour supply runs from Czechoslovakia to Israel, landing at night and departing before dawn. In the latter phase of the war, they flew into crude desert strips, landing and taking off amid swirling dust storms. There were always problems. Somehow the IAF maintenance crews managed to change engines, jury-rig broken systems, and do whatever it took to get the precious transports back in the air before Arab fighters spotted them.

What was the most surprising thing that your research uncovered?

Their combat record. Despite being outnumbered, outgunned, flying obsolete and dilapidated warplanes, the volunteer air force took command of the sky. They downed two dozen hostile warplanes and destroyed many more on the ground. Though numerous aircraft were lost to ground fire and accidents, not a single Israeli fighter was shot down in air-to-air combat against enemy fighters. Most of that high success rate can be attributed to the experience level of the airmen. The roster of the 101 squadron included some well-known names: veteran test pilot Slick Goodlin, Canadian ace John McElroy, Marine Black Sheep ace Chris Magee, and American Rudy Augarten, who became an ace flying four different types of fighters in two wars. By the end of the nine-month war, the little IAF fighter squadron was, man for man, probably the most potent air combat unit in the world.

How much did Israel’s infant air force have in common with today’s successful IAF?

From the first days of the 1948 war, a sobering truth was clear to every airman in the Israeli air force: They were playing a high stakes game. There was no alternative to victory except the annihilation of Israel. To a man, they understood that the survival of the new nation depended on them. That belief was passed on to the next generation of Israeli pilots and became ingrained in IAF doctrine. It has remained with them throughout each of Israel’s subsequent conflicts.

What does your book cover that wasn’t included in documentaries like the 2014 film Above and Beyond?

While Above and Beyond did an excellent job of capturing the historical flavor of the period and the personalities of the airmen they interviewed, it focused almost exclusively on aviators from the U.S. To me, the saga of the volunteer airmen in the 1948 war covers a broader canvas. More than half the airmen came from other countries—Britain, South Africa, Canada, Israel, Belgium, France, Holland, Poland. They were as diverse a bunch as the conglomeration of airplanes they flew. They were eccentric, swaggering, idealistic, and courageous beyond measure. What they achieved was nothing less than a miracle.