A Graphic Reminder of Cost

Can government-funded human spaceflight be cheaper?

Two years ago, we ran a web article about a small band of software developers, model rocket builders, and anonymous NASA space shuttle engineers who were pitting a pair of alternative launch vehicle ideas against NASA's Ares rockets developed for the now-canceled Constellation program. These alternatives, the Jupiter 120 (to reach low Earth orbit) and Jupiter 232 (for lunar missions) were part of a "simpler-safer-sooner" concept that the group called Direct v2.0. The Direct launch vehicle would maximize the use of space shuttle hardware by placing Constellation's Altair lunar lander and Orion crew exploration vehicle atop a slightly modified space shuttle external propellant tank. Unmodified, four-segment solid rocket boosters would be brought forward directly from the shuttle program. (The latest version of the concept is Direct v3.) While Constellation claimed to be developing shuttle-derived machinery with its five-segment boosters, it was clear that Direct's plan would more faithfully use existing hardware.

We liked the creativity and underdog pluck of the Direct guys. And the Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee last year suggested, among several options, an approach very similar to that of Direct for getting back to the moon by the mid-2020s (see p.16, "Variant 4B"). But today, with the economy still struggling, NASA is confronting new questions not just about the engineering of the space shuttle's successor, but the cost. The NASA authorization bill that the president signed on October 11 wasn't much of a victory for the Obama Administration, as it preserves many of the costly shuttle and Constellation pieces the president wanted to get rid of in order to free up money for research on new technologies. In the bill, the Senate dictates very specifically that the new rocket will use lots of shuttle-derived parts, to the point where NASA has had to push back against the politicians.

The bill has inspired the Direct engineers to claim victory in the shuttle replacement debate. Direct's team has formed a new technology company called C-Star Aerospace, LLC, with hopes of being involved in building the new heavy lift launcher.

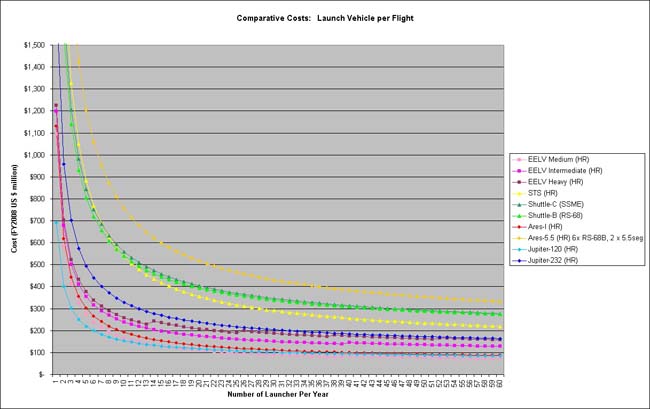

Supporters of the Direct approach claim in the following graph that their Jupiter rocket would save tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars per launch compared to Constellation rockets and the space shuttle. Here's a larger version.

The bottom axis of the graph shows that to get the cost per launch of a Jupiter 232 down to $200 million, NASA would have to launch about 35 of them per year. But didn't the space agency realize early in the shuttle program that such a tempo is impossible? A list of NASA missions over the last 30 years offers a stark reminder of the shuttle's busiest year, 1985, with nine launches, followed by two more in January 1986. The second of those was Challenger.

And what exactly would NASA put in orbit 35 times a year atop a heavy-lift launcher like the Jupiter 232? Perhaps all the parts needed for a Mars mission? NASA's most recent Constellation-based architecture for a human trip to Mars shows seven Ares V rockets required to get the crew, equipment, fuel, and other supplies there, and bring the crew home (see page 13 of this .pdf). Perhaps the Jupiter 232, which is smaller than the Ares V would have been, might need nine or ten launches to do the same job?

From 2000 to 2009, the Delta rocket launched an average of 7.2 times a year; the Atlas, 4.4 times a year. That's with demand not just from NASA, but also military and corporate customers here and abroad. From 1981 through the end of 2010, the shuttle will have launched an average of 4.43 times a year at an all-inclusive cost of around $1.3 billion per flight according to Roger Pielke at the University of Colorado at Boulder. If these programs are any indication, NASA would more realistically end up launching three or four Jupiters a year, each at a cost north of half a billion dollars according to this graph.

Some may say that the shuttle's lengthy down time between missions was the culprit that slowed the schedule. But again, history shows that in the most frantic 12-month period of a blank-check Apollo program sprinting toward its Kennedy deadline, NASA got off five launches, Apollo 7 through 11, from October 1968 through July 1969. None of those rockets carried a high-maintenance shuttle. After the first moon landing, with the pressure of a deadline gone, an average of two manned lunar missions launched each year through Apollo 17.

Even if NASA could logistically launch 35 Jupiters a year, where does the $7 billion (at rougly $200 million per flight, according to the graph) come from? The shuttle program never got a fraction of that kind of money annually.

Bottom line: Human spaceflight run by the government will continue to be very expensive.

We liked the creativity and underdog pluck of the Direct guys. And the Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee last year suggested, among several options, an approach very similar to that of Direct for getting back to the moon by the mid-2020s (see p.16, "Variant 4B"). But today, with the economy still struggling, NASA is confronting new questions not just about the engineering of the space shuttle's successor, but the cost. The NASA authorization bill that the president signed on October 11 wasn't much of a victory for the Obama Administration, as it preserves many of the costly shuttle and Constellation pieces the president wanted to get rid of in order to free up money for research on new technologies. In the bill, the Senate dictates very specifically that the new rocket will use lots of shuttle-derived parts, to the point where NASA has had to push back against the politicians.

The bill has inspired the Direct engineers to claim victory in the shuttle replacement debate. Direct's team has formed a new technology company called C-Star Aerospace, LLC, with hopes of being involved in building the new heavy lift launcher.

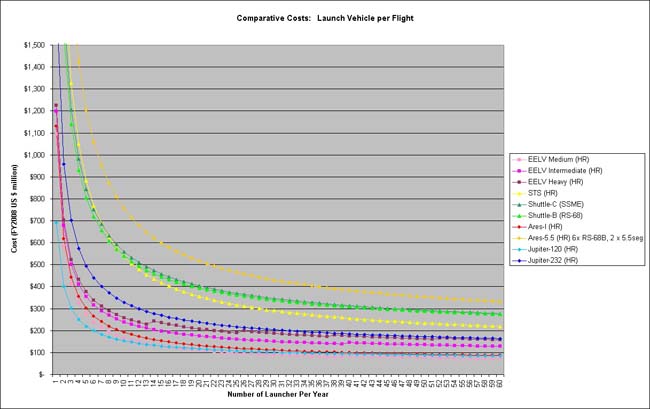

Supporters of the Direct approach claim in the following graph that their Jupiter rocket would save tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars per launch compared to Constellation rockets and the space shuttle. Here's a larger version.

The bottom axis of the graph shows that to get the cost per launch of a Jupiter 232 down to $200 million, NASA would have to launch about 35 of them per year. But didn't the space agency realize early in the shuttle program that such a tempo is impossible? A list of NASA missions over the last 30 years offers a stark reminder of the shuttle's busiest year, 1985, with nine launches, followed by two more in January 1986. The second of those was Challenger.

And what exactly would NASA put in orbit 35 times a year atop a heavy-lift launcher like the Jupiter 232? Perhaps all the parts needed for a Mars mission? NASA's most recent Constellation-based architecture for a human trip to Mars shows seven Ares V rockets required to get the crew, equipment, fuel, and other supplies there, and bring the crew home (see page 13 of this .pdf). Perhaps the Jupiter 232, which is smaller than the Ares V would have been, might need nine or ten launches to do the same job?

From 2000 to 2009, the Delta rocket launched an average of 7.2 times a year; the Atlas, 4.4 times a year. That's with demand not just from NASA, but also military and corporate customers here and abroad. From 1981 through the end of 2010, the shuttle will have launched an average of 4.43 times a year at an all-inclusive cost of around $1.3 billion per flight according to Roger Pielke at the University of Colorado at Boulder. If these programs are any indication, NASA would more realistically end up launching three or four Jupiters a year, each at a cost north of half a billion dollars according to this graph.

Some may say that the shuttle's lengthy down time between missions was the culprit that slowed the schedule. But again, history shows that in the most frantic 12-month period of a blank-check Apollo program sprinting toward its Kennedy deadline, NASA got off five launches, Apollo 7 through 11, from October 1968 through July 1969. None of those rockets carried a high-maintenance shuttle. After the first moon landing, with the pressure of a deadline gone, an average of two manned lunar missions launched each year through Apollo 17.

Even if NASA could logistically launch 35 Jupiters a year, where does the $7 billion (at rougly $200 million per flight, according to the graph) come from? The shuttle program never got a fraction of that kind of money annually.

Bottom line: Human spaceflight run by the government will continue to be very expensive.