How Many High School Kids Can Say They’ve Watched Their Own Satellite Launch into Orbit?

Meet the team behind the TJ3SAT.

Packed tightly among the 28 tiny satellites hitching a ride on last night’s ORS-3 rocket launch from NASA’s Wallops Island, Virginia, spaceport was the first-ever satellite built by high school students.

That’s right—space has now been conquered by super-smart teenagers.

TJ3SAT is named for the state-chartered magnet school where it was built, Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, Virginia. The “3” stands for cubed—the 10 x 10 x 11-centimeter satellite is part of a family of spacecraft called cubesats, whose size and shape are standardized to make them easier to fit into the leftover space around bigger launch payloads.

The project began in 2006 as a course in systems engineering, in collaboration with Orbital Sciences, the Virginia-based company that funded the project. Orbital gave technical guidance to the students, but they built the satellite themselves. Once in orbit, TJ3SAT will receive messages from students and amateur radio operators all around the world and, through phonetic voice synthesizer software, speak the messages “aloud” over a designated radio frequency so they can be heard on the ground.

Adam Kemp, the faculty sponsor for the project, had no trouble getting students excited about sending a satellite to space. He likens Thomas Jefferson to Hogwarts, the wizarding school of Harry Potter fame (U.S. News & World Report ranks it the fourth best high school in the country). “The kids really want to be there,” he says, “so we can take advantage of the fact that they want to be there and start proposing these really high-level tasks. And the kids just eat it up.”

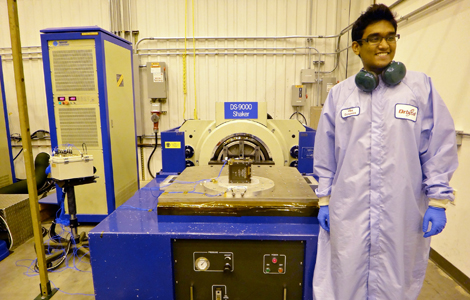

Over the past nearly eight years, Kemp estimates about 50 students have participated in the cubesat project. Almost all have graduated, and many have gone on to top engineering schools like MIT, and from there to jobs in the aerospace industry. At one point the school’s administration cut the course under which TJ3SAT was being built, but Kemp and a few students carried on under the auspices of a senior research project. Over the last few months, only senior Rohan Punnoose has been directly involved in seeing the project through to its hour of glory.

Punnoose is already an accomplished engineer—among other things he’s led another team at Thomas Jefferson in building and successfully deploying an autonomous rover from a high-powered rocket. But, he says, TJ3SAT is the coolest thing he’s ever done. Standing in a chilly field a few miles from the launch pad with Kemp and several former students who worked on the project, Punnoose got to watch his school’s crowning achievement blast into space on a sun-bright arc of fire and sound. The kids cheered while Kemp let out a euphoric laugh.

“Alright, TJ!” he shouted.

Like many cubesats, TJ3SAT had to wait for its ride to space. The team’s opportunity finally came when there was extra room on Orbital’s Minotaur I rocket, which was delivering a larger and much more expensive satellite into orbit (the U.S. Air Force’s STPSat-3 will measure the sun’s energy output). TJ3SAT made it onto the manifest through NASA’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites (ELaNa) program, along with cubesats from nine universities around the country. Punnoose had the honor of escorting his school’s completed cubesat to Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico, where it was added to the payload that would eventually be shipped to Wallops for the launch. “I was the last person to touch it, which is amazing,” he says.

Punnoose says the cubesat, if it works, should last at least a few months, but could go a couple of years before it no longer answers its mail. The cubesat itself, like any technology, will eventually stop working, but it may deorbit and burn up in the earth’s atmosphere long before that.

In the meantime, TJ3SAT has a lot of work to do. Amateur radio operators can start submitting short messages on the project’s website today after the satellite makes its first pass within range of the ground station at Thomas Jefferson, and if all goes well, the spacecraft will start talking immediately.

The first official message TJ3SAT returns to earth will be something like “Go Colonials,” a shout-out to the high school’s mascot. But before that will be another message, some kind of inside joke between the satellite and its makers, but Punnoose won’t let on what it is.

“That’s a secret,” he says, practically winking at the sky.

Submit a message at the project site, or track the satellite here.

Mark Betancourt is a writer based in Washington D.C. and a frequent contributor to Air & Space.