Beavers On Parachutes

In 1948, Idaho decided the best way to move beavers was to airdrop them

:focal(1171x476:1172x477)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/98/0598cb91-ea49-42a1-9072-c8f327e22674/parachuting_beaver.jpg)

Just the title — Transplanting Beavers by Airplane and Parachute — of this 1950 report in the Journal of Wildlife Management raises questions. Like, for goodness sake, why? And how? Did they specially make tiny beaver-sized parachutes and goggles, and push them out of the cargo hold, one by one, like a tiny dam-making army? Once on the ground, did the beavers suffer post-traumatic stress from the sudden drop? Or did they spend the rest of their days mourning in rivers, longing for another taste of the sky?

Fortunately, the article by Elmo W. Heter from the Idaho Fish and Game Department answered all our questions. Even before the parachuting began, the agency had been in the practice of transplanting beavers whose populations had outgrown their habitats so that they became an annoyance on farms and orchards. But the mountainous, forested and “generally inaccessible wilderness” in Idaho had “complicated the beaver-transplanting program,” the report explains. The game department tried moving them by horse and mule, but it was “arduous, prolonged, expensive, and resulted in high mortality among the beavers.” Not to mention that the pack animals became “spooky and quarrelsome” after dragging the understandably upset beavers for days and days.

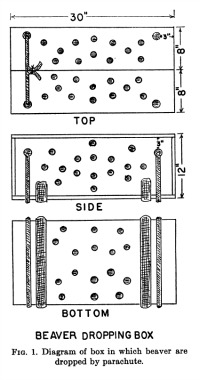

Heter doesn’t say exactly how he and his colleagues came up with the brilliant idea of an airdrop, though we’d like to have been in on that meeting. They got war surplus parachutes from the Idaho Forest Service, and placed the animals in boxes, one pair in each box. Settling on the release mechanism required some innovation:

The first box tried had ends made of woven willow. It was thought that, since willows were a beaver’s natural food, the animal would gnaw his way to freedom. This method was discarded when it was discovered that beavers might chew their way out of these boxes too soon, and be loose in the plane, or fall out of a box during the drop.

Finally, they rigged up a tension-banded box that cinched tight from its own weight in the air, but snapped open to let the beavers out once reaching the ground. After concluding that 500 to 800 feet was the ideal beaver-dropping altitude, it was time to go airborne.

Satisfactory experiments with dummy weights having been completed, one old beaver, whom we fondly named “Geronimo,” was dropped again and again on the flying field. Each time he scrambled out of the box, someone was on hand to pick him up. Poor fellow. He finally became resigned, and as soon as we approached him, would crawl back into his box ready to go aloft again. You may be sure that “Geronimo” had a priority reservation on the first ship into the hinterland, and that three young females went with him. Even there he stayed in the box for a long time after his harem was busy inspecting the new surroundings. However, his colony was later reported as very well established.

During the 1948 fall season covered in Heter’s report, only one of 76 beavers failed to survive the flight to his new home, due to lightweight ropes used on the first set of drops that allowed him to wiggle out of the box and climb on top. “Had he stayed where he was, all would have gone well; but for some inexplicable reason, when the box was 75 feet the ground, he jumped or fell from the box,” wrote Heter.

One wonders what the native fauna thought of all these beavers dropping from the sky. At any rate, transplanting via parachute saved money and man hours, and left the animals healthier at the end of their journey. When Heter’s team checked in on them the following season, each of these Felix Baumgartners of the animal kingdom had acclimated successfully to their new homes.

Thanks to Mal McKay and Kelly Rand for the tip.