Into the Danger Zone, Tied to a Balloon

When you’re about to send someone on a solo ride to the stratosphere, you work through problems and put your faith in the math.

:focal(1152x561:1153x562)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/80/ff80eede-284d-4ec7-916e-d8d7d0d9ca1e/eustace_cover_image.jpg)

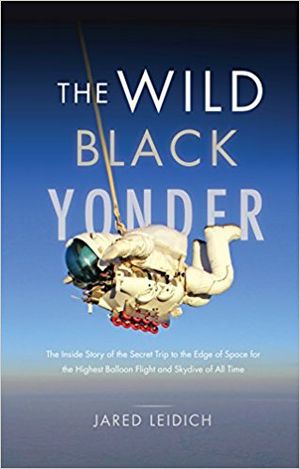

Computer scientist and former Google executive Alan Eustace successfully jumped from an altitude of 135,899 feet in 2014, a feat that still stands as the highest skydive ever. Jared Leidich was the engineering lead for Eustace’s suit, which was the aeronaut’s only protection from the cold and near-vacuum of the stratosphere. In this condensed excerpt from his book, The Wild Black Yonder, Leidich recounts the tense moments leading up to a launch.

All engineers know that if something they design doesn’t work correctly, it could kill someone. I’m sure a few people have died using blenders, but not many. People die in cars and airplanes all the time, but lots of people use them and live. In our situation, only a handful of people had used equipment resembling ours—and nearly half of them had died. If Alan was injured or killed, we couldn’t hide behind committees or bureaucracies. We had built the thing. We were responsible for what it did.

Exactly three drops were left in the program. Alan would ride to successively higher altitudes in a spacesuit attached to a balloon and skydive from the stratosphere.

We woke up at midnight. The night sky waited, cool and calm, for the aeronaut to go further than most. For over two years we had imagined the sight of our fragile suit hanging below a plastic inverted teardrop, but now all I could imagine was a feeble white cartoon character set against the black-blue fringe at the top of the troposphere.

Before every early-morning test, the suit team met at the local IHOP to find our groove before stepping into the furnace. We always sat in the same places and got the same meals. We didn’t talk much. This was part of a meditation that closed our minds to outside influence, blinding us to the distractions that lead to mistakes that lead to disaster.

At the launch site later, at step 547 of a 1,922-step procedure, came the inevitable hitch, the thing we hadn’t thought of. Sometimes when you put on a ski glove, a finger can get twisted around so that it resists every effort to straighten it out. That’s what happened. We couldn’t get Alan’s pinky into the right-hand glove. We decided to close Alan into the suit and pressurize it so the pressure would pop the finger out. But even with the suit at full pressure, it still wouldn’t flip. Our spare glove happened to be in Houston undergoing a repair on its heater.

The minutes of our well-schemed timeline fell away. I tried to use my hand to free the pinky; Mitch Sweeney and Ryan Lee, two of the suit designers, pulled out plastic integration rods to try to push through the sticky rubber.

Alan watched through the bubble while we cut apart a glove that his life very directly depended on. Mitch fiddled with a flashlight and saw that the pinky of the glove had twisted into itself at the tip. After over an hour of wrestling, he got the pinky flipped with some flashlight tricks and a plastic integration rod. Alan put the glove on, and after some battle with the still-not-quite-straight pinky bladder, all the fingers were back in.

Mitch calmly hand-tacked the cover layers back together, missing the pressurized bladder with the sewing needle every time he plunged it through for another stitch, while Alan held his hand steady as a marksman and watched. For the fourth gut-condensing time, Alan was pressurized in the suit.

**********

The balloon looked tiny. Although it would be the size of an apartment building when it flew, this was the smallest zero-pressure balloon we had ever filled. It seemed dauntingly little, and even feistier as a result.

We took Alan off his cooling hoses, disconnected his flight power, and dropped him on his launch sedan while the balloon bazookas thundered to life. The two people holding the crown valve let go, and the balloon bubble whumped into the air above the spool.

The preparations continued. We were shocked several times when Alan moved, forgetting that there was actually a human in the suit. Between our history with inanimate aeronauts and how stoic a person can become sitting bound in a spacesuit, Alan’s movements had the effect of a stone statue reaching at you in the night.

The balloon snapped around and whapped itself, lashing and whipping in little tantrums. It was hard to tell if it was a healthy balloon or not. It was scary to watch and even scarier to consider hooking a human to.

Even though the angry plastic sheets were flapping against the balloon belly, the stats said she was harmless. We put our faith in the math. We would launch.

Mission control turned on their cameras. And called a hold. Mission control was not able to see Alan’s arms through the live flight camera. Arm signals are an integral part of the mission.

Rolfe Bode, one of the test engineers, scurried in with the plan to cut the camera free of its housing and adjust its angle in real time, but it was quickly clear that the camera wasn’t going to move without minutes or hours of work. Mission control called an audible. Alan was told that whatever the procedures said he should do with arms, he should do with his legs instead.

For the second time we stepped back. The angry swirling orb continued to aggress the space around it, whapping at our nerves. The calmest person there was Alan, leaning his head against the suit helmet bubble, waiting for whatever it was we were doing to end so he could get his flight under way.

Calm settled in. We all quieted down. John Straus, the launch manager, yelled, “Collar!” At the pull of the initiation line, the canvas collar popped off the bubble and swayed to the ground. With the balloon now free to spinnaker and truly rip itself and its surroundings apart, there was no more time. John lunged back a step and called, “Go!” Joe Levy, his deputy, pulled the cord. The ground tethers released. Alan was in the sky.

After all that angry thrashing, the balloon went nearly straight up, without so much as a quiver. Cheers erupted, but not from me. I didn’t like people cheering while Alan was in the dangerous black zone. I would cheer to myself silently in four minutes, when Alan was high enough to use his parachute.

The balloon slowly untwisted. Alan waved at us each time he turned a circle. A scrap of plastic from the wrapping around the balloon stalk freed and floated to the ground.