The First Hydrogen Bomb

Sixty-five years ago, a test of a fearsome new weapon.

:focal(724x457:725x458)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/29/55296f47-c098-4e5c-bdaf-cb384533055c/ivymikea1477c25.jpg)

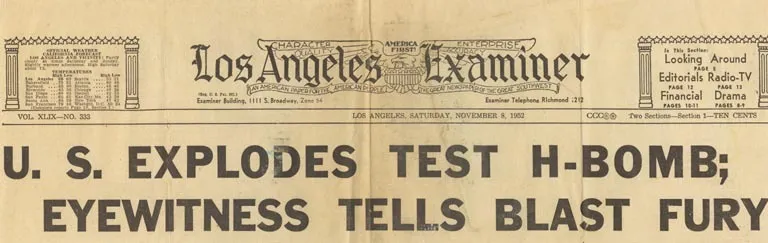

Had you opened your morning paper 65 years ago today, looking for news of one of the most dramatic events in history—the first explosion of a thermonuclear “hydrogen bomb” on November 1, 1952—you would have found…nothing.

Same with the next day, and the next. On Wednesday, November 5, the papers would have been full of stories about Dwight Eisenhower’s election as President the day before. On Friday, a few writers started to hint that a huge bomb had been exploded out in the Pacific. It wasn’t until the next day, a week after the “Ivy Mike” test, that an article appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner, based on a single eyewitness account. The anonymous observer had been on the command ship USS Estes off the Eniwetok atoll, some 30 miles from the blast, which unleashed 10.4 megatons of energy—1,000 times that of the Hiroshima bomb, and twice the total explosive power of all the bombs dropped in World War 2.

“All we could do was stand there and gasp in amazement and awe at the enormous size and force released before us,” the witness had written in a letter to a Los Angeles resident, who forwarded it to the Examiner. “Typical comment from the old timers: ‘Holy Cow! That sure makes the A-bomb a runt.’ ”

In fact, the Ivy Mike test device—it wasn’t a deliverable bomb, since it weighed 82 tons—used a Hiroshima-style fission bomb as the trigger to set off fusion reactions in a large dewar of super-cooled deuterium, or heavy hydrogen. The development of such a fusion weapon had been no secret. But the first test was supposed to have been. Of the thousands of scientists, engineers, technicians, and military personnel who observed the Ivy Mike test, some were so awed by what they saw that they couldn’t resist writing letters to friends and loved ones back home. Sixteen of these letters leaked their way into newspapers around the country, so that by late November the secret was out, even though it would be many more weeks before the Atomic Energy Commission confirmed that the United States did in fact now have the “H-Bomb.”

Sixty-five years later, there are no bombs in the U.S. nuclear arsenal with as big an explosive yield as the Ivy Mike device. And that makes the 65-year-old accounts of a 10-megaton blast all the more compelling to read.

The explosion vaporized an entire small island in the Eniwetok chain. You won’t find Elugelab on the map anymore, just a hole where it used to be.

Pilots who flew in and around the mushroom cloud during the test to monitor the effects of the blast watched the indicators on their radiation counters go around “like the sweep second hand on a watch.” Richard Rhodes, the great chronicler of the early atomic age, describes the scene on the air and on the ground in his masterful history, Dark Sun.

[The blast] expanded in seconds to a blinding white fireball more than three miles across (the Hiroshima fireball had measured little more than one-tenth of a mile) and rose over the horizon like a dark sun; the crews of the task force, thirty miles away, felt a swell of heat as if someone had opened a hot oven, heat that persisted long enough to seem menacing. “You would swear that the whole world was on fire,” one sailor wrote home….

Swirling and boiling, glowing purplish with gamma-ionized light, the expanding fireball began to rise, becoming a burning mushroom cloud balanced on a wide, dirty stem with a curtain of water around its base that slowly fell back into the sea. The wings of the B-36 orbiting fifteen miles from ground zero at forty thousand feet heated ninety-three degrees almost instantly. In a minute and a half, the enlarging fireball cloud reached 57,000 feet; in two and a half minutes, when the shock wave arrived at the Estes, the cloud passed 100,000 feet. The shock wave announced itself with a sharp report followed by a long thunder of broken rumbling.

Back home, reactions ranged from fascination to relief (that Americans got there first) to dread. Wrote author Michael Amrine about the new weapon, “It is a club with which men can kill cities as easily as they once killed each other.”