Flying While Female

China has selected its first two female astronauts, Space.com recently reported. But, unlike their male counterparts, females have to be married. “We believe married women would be more physically and psychologically mature,” Zhang Jianqui, the former deputy commander of China’s spaceflight program…

China has selected its first two female astronauts, Space.com recently reported. But, unlike their male counterparts, females have to be married. “We believe married women would be more physically and psychologically mature,” Zhang Jianqui, the former deputy commander of China’s spaceflight program, is quoted as saying.

The Guardian goes one step further: They’ve reported that in addition to being married, the women must be mothers in order to qualify for the space program. The story reports that “Officials are concerned that space flight might affect fertility.”

When will we be done with this malarkey?

For the record, Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova gave birth to a daughter one year after her 1963 flight. In Principles of Clinical Medicine for Space Flight (edited by Michael R. Barratt and Sam L. Pool in 2008), the authors note that 15 children have been born to 13 U.S. female astronauts who have completed at least one space flight.

If the Chinese are so concerned about the effects of space flight on reproduction, why aren’t male applicants required to be married with children?

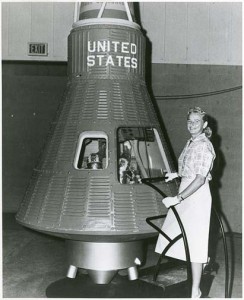

During World War II, physicians believed that Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) shouldn’t fly during the “dysfunction of their menstrual cycle.” As Molly Merryman wrote in her history of the WASP, Clipped Wings, the Army Air Forces, after much study, concluded that menstruation had no effect on female pilots. But just a few years later, when a group of female pilots (usually referred to as “the Mercury 13”) was undergoing the physical tests for astronaut training, NASA wasn’t sure women could physically handle the demands of space. As journalist Martha Ackmann reported in The Mercury 13: The True Story of Thirteen Women and the Dream of Space Flight, some of the Mercury 13 “received advice from former WASPs about how to respond to the inevitable ‘menstruation question’ from physicians…. Women who served in the WASPs were so accustomed to hearing medical doctors voice concern about women flying during their menstrual periods that they developed their own response that allowed them to keep flying any time of the month. When asked by medical professionals, ‘How often do you get your period?’ many of the WASPs responded by saying they were ‘highly irregular.’ ”

Another reason given to keep U.S. women from being astronauts included the military's assertion that partial pressure suits, worn by pilots and astronauts to survive high-altitude flight, couldn't be adapted to fit the female form. (This despite that fact that David Clark, a major manufacture of pressure suits, designed them using women's brassieres as a model.)

Ackmann includes the 1963 assessment of NASA psychologist Robert B. Voas, who felt the women-in-space program to be ridiculous: "As for the ladies' alleged ability to withstand boredom and confinement better than the man, I think there might be a number of harried husbands who have sat through long evenings listening to the wife's recitations of the day's activities, who have credentials in the area of tolerance and boredom."

And then there are the mind-numbing comments of Wernher von Braun, given in a 1962 speech on the Mississippi State College campus, on whether women should be in the space program: "Well, all I can say is that the male astronauts are all for it. And as my friend Bob Gilruth says, we're reserving 110 pounds of payload for recreational equipment."