Kepler’s Catch

When a veteran planet hunter like Debra Fischer calls it the most momentous discovery since 51 Peg, you know it must be big.In 1995, scientists found the first planet circling a normal star outside our solar system—an unassuming yellow dwarf called 51 Pegasi. In the 16 years since, they’ve identifi…

When a veteran planet hunter like Debra Fischer calls it the most momentous discovery since 51 Peg, you know it must be big.

In 1995, scientists found the first planet circling a normal star outside our solar system—an unassuming yellow dwarf called 51 Pegasi. In the 16 years since, they've identified more than 500 such exoplanets.

Today they tripled the total in one announcement.

Actually, the Kepler spacecraft science team is only claiming 1,253 new candidate planets, based on four months of staring at 155,000 stars in the constellation Cygnus. Most still need verification with ground-based telescopes, and perhaps 20 percent of the claims will wash out, according to Fischer, who was on the panel presenting the Kepler findings to the press today.

Still, the number is impressive. According to Kepler project scientist William Borucki, his telescope is only surveying 1/400th of the sky. So by extrapolation, half a million new planets might be out there, easily detectable with a Kepler-style telescope, which watches for dips in light as a dark planet crosses in front of a bright star.

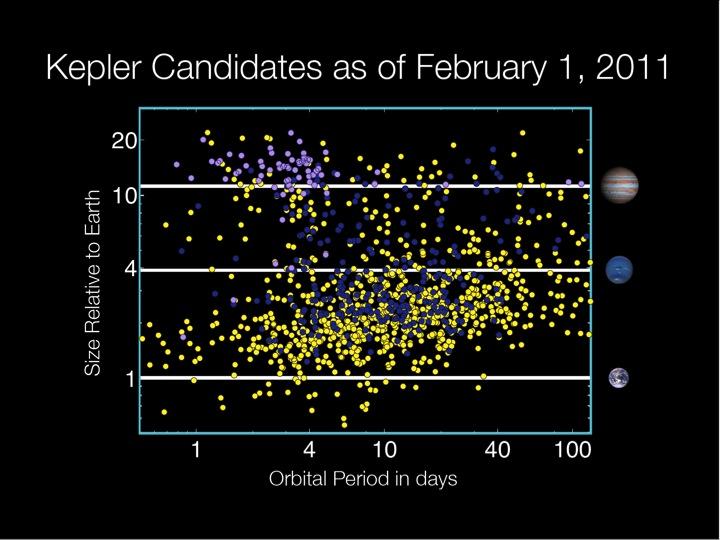

Kepler's new batch of 1,253 candidates includes 68 Earth-size- planets, 288 "super-Earths" (twice as big as our own world), 662 the size of Neptune, and 165 the size of Jupiter. The telescope even found one sun-like star called Kepler-11 with six planets, a record.

A whopping 54 of the new candidates orbit in the so-called habitable zone of their star, where temperatures would theoretically be moderate enough for life to exist. And five of those 54 are Earth-size.

Finding a true Earth analog—a planet the size of our own, circling a star similar to the sun at roughly the same distance—requires three years of data. That's how long it will take to get repeated crossings of the sun's disk for orbits the size of Earth's.

So, says Borucki, we'll need patience to find a close match of our own planet around another star. But that doesn't mean some of the 54 planets announced today, or even their moons, couldn't harbor life of some kind.

Meanwhile, you can join in analyzing the Kepler data at the "Planet Hunters" site. So far, says Fischer, some 16,000 people around the world have participated in this nifty example of "citizen science." They've already turned up hundreds of candidates, most of which are likely to overlap the list released today by the professionals.