Airplanes of the Stars

Show performers talk about their favorite rides.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/stars-airplanes-0508-main.jpg)

When National Air and Space Museum docents tell visitors about the historic airplanes in the collection, they often draw on stories told by the people who know the airplanes best: the donors. Last year aeronautics curator Dorothy Cochrane invited airshow star Patty Wagstaff, performers Steve Oliver and Suzanne Asbury-Oliver, and Judy Scholl, wife of the late aerobatic showman Art Scholl, to give docents the inside scoop on three of the Museum's top-performing showplanes. Docents now have the following stories to add to their tours.

No one can accuse Walter Extra, who refused to sell it to her.

Wagstaff said the first time she saw a photo of the Extra 260, which was installed in the Museum in 1994, she knew she had to have it. She was competing in the 1988 World Aerobatic Championships in Red Deer, Canada. "I'd never seen an airplane like it," she said. "It was sleek and fast-looking, but it was a prototype and Walter said it wasn't built to withstand the rigors of hard-core aerobatics."

When Extra sold the prototype a year later to Brian Becker, who ran Pompano Air Center in Florida, Wagstaff bought the airplane from him. "I flew it every day, every day, every day," she said, smiling, to the assembled group of docents.

I saw her fly the 260 once, at Andrews Air Force Base in June 1993, her last demonstration before retiring the airplane. I still remember the performance. It was so crisp, yet so exuberant. The airplane, which has a roll rate of 360 degrees a second, appeared to dance with itself. I could almost hear a little "ta-daaaa!" at the end of each precisely executed, rollicking combination of rolls and climbs and tumbles and dives. But by that time, said Wagstaff, "Things were starting to [break] on it."

"Walter was absolutely right," she said. "It was underbuilt [for aerobatics]." Wagstaff had broken a longeron at an airshow in 1992, and when Museum staff took the airplane apart to hang it in 1994, they had a hard time getting the wing off because the spar bolts holding the wing on were bent.

"The 260 was so fast and had such a clean frontal area that it was really easy to over-G it," she said. "That's why it was breaking." The G meter on the aircraft, which is on display in the Pioneers of Flight gallery on the second floor of the Museum in Washington, is still set at 12 Gs, the last mark Wagstaff hit that day at Andrews.

Suspended from the ceiling of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia since the Center opened in 2003, Suzanne Asbury-Oliver's historic Travel Air D4D Pepsi Skywriter presides over the other showplanes. "I like seeing it way up high, looking down on everybody else, because that's where we did our work—up around 10,000 feet," Oliver told the docents. The "we" refers to her and the airplane, and the work: one of the rarest occupations in the world. "How many skywriters are there today?" an audience member asked. "You're looking at 'em," Oliver answered.

The world's last skywriter got her start by answering a 1980 advertisement in the publication Trade-a-Plane and trying out from the back seat of a Piper Super Cub. "What can you see?" Pepsi's chief pilot at the time, Jack Strayer, asked her from the front seat as they sat on the runway. Strayer knew that what Oliver was seeing from the backseat would be about what she'd see when skywriting in a TravelAir: not much. She wouldn't be able to see the letters she would be expected to write; rather she'd have to feel and calculate, almost like flying blind. "Nothing," she answered. "Good," said Strayer. "Let's go."

"I guess I did alright because he hired me," Oliver told the docents. "I was 21 when I started flying [the Travel Air]," she said, "and we sort of grew up together."

The airplane is one of the originals that wrote "Pepsi" in the sky in the 1930s. "So it was a working airplane for seven decades," aerobatic pilot Steve Oliver, Suzanne's husband, told the audience. Today the couple writes and performs aerobatics in a modified deHavilland Chipmunk, the Oregon Aero SkyDancer.

A skywriter's contract includes a provision, according to the Olivers, not to reveal the secrets of their profession. But Steve, who learned from Suzanne, who learned from Strayer, explained a few of the tricks. "It's all counting," he says. The pilots count as they fly—one one-thousand, two one-thousand, along the upright of a T, say—so the letters, which are flat, not vertical, will all be the same size. The rate of turn and the altitude must be held precisely or the letters, which are about 3/4 of a mile tall, will look sloppy or be unreadable. (The word "Pepsi" stretches six or seven miles from the "P" to the "i.") "If you're two degrees off on a heading," said Steve, the pilot can't join the vertical and horizontal parts of a letter correctly.

A bigger hazard for Suzanne, she said, is forgetting the letter she has just written. She once wrote "P-p-e-p-s-i" at a show in Chicago. "I told them it was so cold that I was stuttering," she said.

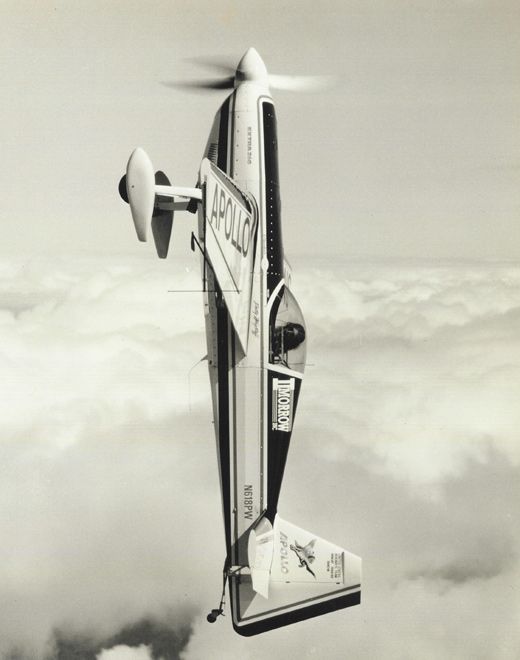

Steve Oliver, who flies the Chipmunk in a night-time "pyrobatic" act, follows in the footsteps of one of the pilots who originated that kind of flying, Art Scholl. Scholl was represented by his wife Judy, who, while showing video clips Art had created of his performances, commented that he chose and modified the San Bernardino Valley College for 18 years, was killed in a Pitts Special camera aircraft during the 1985 filming of Top Gun. One of his two showplanes, donated to the Museum in 1987, also hangs at the Udvar-Hazy Center.

Scholl, famous for his showmanship, pioneered many of the features still seen in airshow routines. Besides the night pyrotechnics act, he performed a special type of ribbon cut. "Actually, it wasn't a ribbon cut," said Judy, "if he cut the ribbon, he considered the stunt a failure." Scholl flew inverted over a ribbon, and so controlled was his touch that he lifted it into the air instead of severing it in two.

With his little dog Aileron in the cockpit with him, Scholl spread the word that flying was fun. Seeing him in a 1950s film, speaking matter-of-factly to the viewer while he cruises into the frame—upside down—you definitely get that message.