A Game For Your Inner Spy

Visitors learn about the cold war in a new role-playing game

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/7d/2e7da9fa-96e1-4e5a-a363-66996e919e5a/16e_fm2015_nasm2014-06589_live.jpg)

Rachel Dunning stands in front of 16 children—er, intelligence analysts—gazing out from behind a pair of extremely cool dark glasses. “One of our aircraft on a top-secret mission is missing and we believe it has gone down,” she says. “We brought you here today because you’re the best intelligence analysts in the area. You’ll need to collect and examine evidence and make an important decision. President Johnson has given us authority to use every resource to find the aircraft.”

Wait a minute—President Johnson?

That’s right. Every Saturday at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy, it’s September 1967, and visitors learn all about the cold war in a role-playing game called “Smithsonian TechQuest: Eye in the Sky.”

We analysts start the game by looking for clues in high-resolution aerial photographs. Dunning encourages us to guess the time of day and the season when the photographs were taken and to determine whether it was on a weekend or weekday. We’re also told to take the photographs’ resolution into consideration. Are the images sharp enough to identify a specific aircraft, or is the quality so poor that we see just a smudge, which could indicate debris?

Our group includes an extended family of 16, which has split by gender into two teams; a family of four, with two young boys; and two teenage girls who learned about the game while standing in line for an IMAX movie.

After the briefing concludes (“You do not want to blow your cover by running!”), the kids head out to the collections. Using four artifacts—and with the help of “senior advisers” stationed throughout the Museum—participants devise a plan to rescue the downed crew and their top-secret technology.

The game was inspired by Colonial Williamsburg’s RevQuest, says Tim Grove of the Museum’s education department. (RevQuest is a role-playing game set in the summer of 1775, which players start online before traveling to Colonial Williamsburg. They receive a “spy score,” and go undercover and continue playing once they arrive on site.) “RevQuest has a strong narrative, but it also has a lot of code-breaking and puzzles that you solve along the way,” says Grove. “We thought the concept could be adapted to our very different environment, and engage the audience we’re trying to reach: upper elementary school and middle school.”

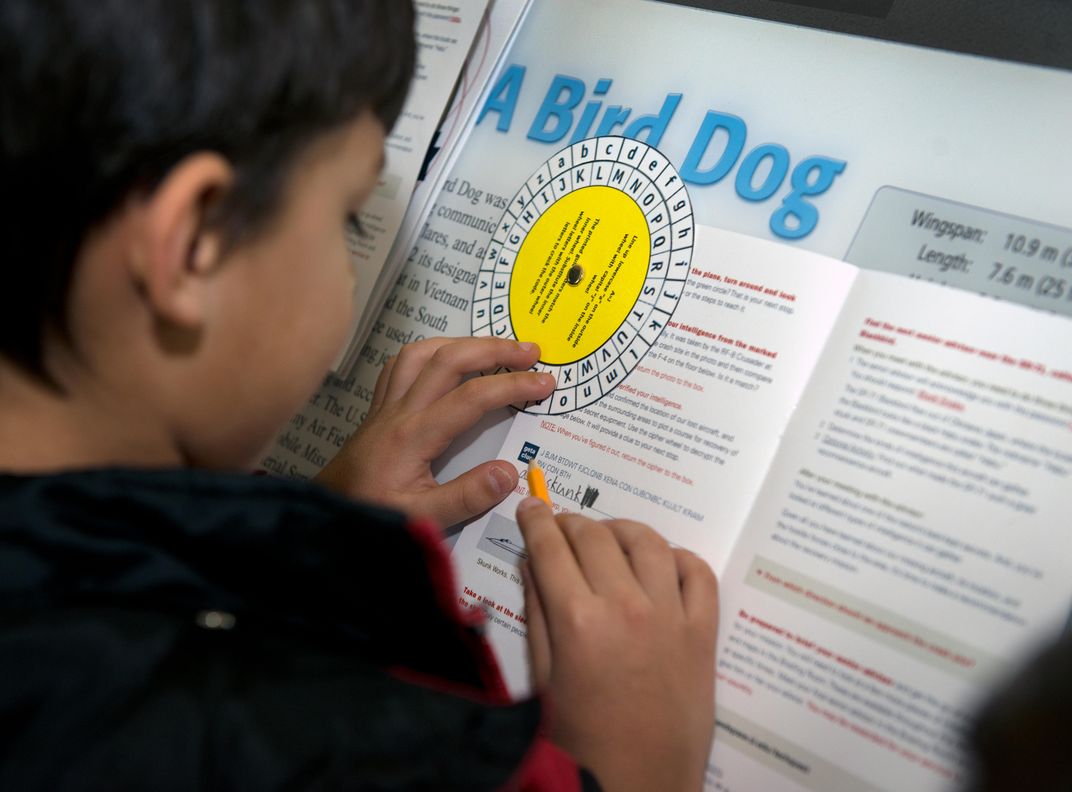

Advisers greet each player with a password; after supplying the correct response, players are given a piece of intelligence—sometimes encrypted—to help locate the downed aircraft.

With a little help from advisers, the teams, using satellite imagery, plot latitude and longitude lines to determine the crash site, decode line/ word/letter ciphers to find additional clues, and basically roam all over the vast Udvar-Hazy Center.

Once they’ve answered all the clues, players attend a debriefing, then explain their rescue plan to a senior adviser, who may suggest how to improve their strategy.

The Museum has a four-year grant—funded by McDonald’s—to run the program, and the staff plans to change the game topic each year. “In the future,” says Grove, “we’d like to add an online element. This particular game doesn’t use technology like smartphones to play the game.” Instead, he says, the “tech” in “TechQuest” comes from the content. “We’re dealing with artifacts that were highly technological in their day,” says Grove. “Two of them were top secret, something the general public didn’t know about.”

The game takes about 60 to 90 minutes to complete, and doesn’t have to be played all at once, should visitors wish to stop for lunch or a movie. “The game is for ages 10 and above,” says Grove, “but ideally it becomes a multi-generational group playing it together.”

The game is offered every Saturday throughout the day, and one Friday each month. Visit airandspace.si.edu/techquest to learn more.