An Aircraft Saves the Day

Five daring helicopter crews on five very bad days.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rescued-Opener-631.jpg)

From their first appearance in military operations, when they were sent to ferry supplies during the closing months of World War II, helicopters have been pressed into service to rescue the endangered and the wounded. With the ability to fly low and slow, hover in one spot, and land virtually anywhere, rotary-wing aircraft turned out to be the perfect search-and-rescue vehicles. But the attributes that make the helicopter so useful also make it vulnerable, in combat zones, to enemy fire. And its utility has not been without cost: For every seven men saved during the Vietnam War, notes a Naval Air Command study, one rescue crew was lost. Such statistics help explain how helicopter crews earn reputations for uncommon bravery.

These five search-and-rescue missions showcase the remarkable capabilities—and flexibility—of the helicopter and the pilots who fly it.

***

The Sikorsky HH-60 Jayhawk was hovering rock-steady over the water, but the radar altimeter kept fluctuating wildly between 100 and 30 feet. Not because there was something wrong with the instrument, but because the waves roiling beneath the Coast Guard helicopter were cresting at 70 feet.

Think about that for a moment: waves the height of a seven-story building. And floating in those angry, froth-filled seas, being tossed around like a rubber duck in the bathtub of a petulant child, was a raft holding three shipwrecked sailors.

It was May 7, 2007, and earlier that morning, Jean Pierre de Lutz, Rudy Snel, and Ben Tye had abandoned ship after their 44-foot cutter Sean Seamour II capsized off North Carolina during Tropical Storm Andrea. (Two other boats also went down in that storm, and one disappeared without a trace along with its charter crew of four.) Although the three managed to launch a raft, their emergency homing device failed, and they’d resigned themselves to being lost at sea. Even after they were spotted by a Coast Guard C-130, they assumed the appalling conditions made rescue impossible. Obviously, they weren’t familiar with the immensely capable Jayhawk. “It’s really a monster truck with two jet engines and a huge fuel tank in the back,” says the helicopter’s commander, Nevada Smith.

The C-130 vectored the chopper to the raft, where pilot Aaron Nelson fought rain and violent headwinds to maneuver into position. (Although the airspeed indicator showed 70 knots, the ground speed was zero.) While Nelson hovered at 100 feet, flight mechanic Scott Higgins lowered rescue swimmer Drew Dazzo by winch into the water, timing his splashdown so that he entered on the back side of a wave. Dazzo unhooked from the cable so it could be retracted back into the helicopter, then swam to the raft. When he got there, he draped an elbow over the side and matter-of-factly asked the dazed sailors, “How you all doing?”

De Lutz was in the worst shape; he’d broken ribs, and hypothermia was making him slip in and out of consciousness. Dazzo held both arms over his head to signal that he needed a rescue basket, so Higgins winched it down, and Dazzo took de Lutz up. When he returned to the water, Dazzo was swamped by a wave the size of a drive-in movie screen. The wave ripped the mask off his face and inundated him with saltwater. Nevertheless, he managed to take Snel up. Then, after securing Tye inside the basket, he sunk the raft by puncturing it with his knife, so another Coast Guard crew wouldn’t see it and attempt a rescue. So far, so good. But as Higgins winched Tye up to the helo, he felt the cable starting to fray. Dazzo, meanwhile, was vomiting and fighting for breath as he fought the powerful seas. Exhausted, he flashed the emergency pickup signal. Higgins disconnected the basket and immediately lowered a bare hook into the water. Dazzo hooked it to himself, and was hoisted into the bird. The process wrenched his back badly, but he and the three shipwrecked sailors were alive.

The rescue operation took 28 minutes. During that time, the helicopter flew backward 1.8 miles to maintain station on the raft. Once the men were back at the base, the air crew gorged on sandwiches left over from an airshow that had been canceled because of the storm. “We were euphoric,” Smith says. “In military aviation, you’re naturally paranoid because you’re always waiting for something to go wrong. But that day was why you join the Coast Guard, why you become a rescue swimmer, why you become a pilot.”

***

The morning after Hurricane Floyd tore through the Carolinas in the fall of 1999, the weather for flying was perfect. Which was a good thing, because Curt Pool and his Marine Corps crew needed as much time as possible to rescue residents and motorists who had been stranded—or worse—by rising flood waters.

Pool and copilot Shane Hill were flying a Boeing Vertol CH-46D, a long-in-the-tooth warbird officially dubbed the Sea Knight but, because of its homely looks, popularly known as the Phrog. “There’s nothing sexy about it,” Pool says, “but it’s fun to fly, and with the twin rotors, you don’t get pushed around too much by the wind, which makes it a good search-and-rescue platform.”

Pool launched out of the Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point, North Carolina, in search of motorists whose cars had been engulfed in water. But as soon as the crew arrived on the scene, it was besieged with emergency calls from local police, and the helicopter spent the rest of the day criss-crossing the area in search of survivors. Pool and Hill swapped flying duties according to which had the better visual reference for hovering. Among other missions, rescue swimmer Corey Beem plucked a trucker from a tree. Flight surgeon Mark Pressley treated a driver who had suffered a heart attack. And Corpsman David Clipson was center stage for not one but two high-intensity rescues.

The first involved a family of four who had taken refuge in the attic of their three-story house in Nashville County. By the time the Phrog arrived, water was rising past the second floor. Pool hovered 50 feet over the roof between trees and power lines, but almost as soon as crew chief Ed Morris started winching Clipson down to the house, the system “birdcaged,” locking the rescuer in a useless position. So Clipson was hauled back up into the chopper, where he set up a rope he could use to rappel down to the roof, manually controlling his own descent and then relying on the helicopter to short-haul him to safety. Clipson landed on the roof, climbed onto a ledge, and entered the attic through a dormer window. Many round-trips later, the family was safe.

With the house evacuated, Clipson repacked his rope so he could again use it for rappelling. A few hours later, it came in handy: The helicopter was dispatched to rescue two firefighters stranded in a small boat—one they had been using for swift-water rescue operations, ironically—whose motor had died. The raging floodwaters had pinned them against a giant pine tree, and the large branches obscured them from above. So Clipson rappelled down to the water, and the helicopter inched him toward the boat. Then, disaster.

“You need a stable hover reference,” Pool says. “If you’re looking at the water and it’s moving, it gives you the impression that you need to move, so you start drifting.” Just as Clipson reached the boat, he was dunked in the water. His waterlogged gear dragged him under and he nearly drowned. But he was able to grab the edge of the boat and muscle his way back up to the surface. “Can you guys help me out?” he asked the firefighters, but they shook their heads, afraid that if they moved the boat would capsize.

Clipson found a branch to support one foot, and he flopped into the boat like a hooked fish. Eventually, the helicopter short-hauled both firefighters through the tree branches to safety, bringing the crew’s rescue tally for the day to nearly a dozen. “It was crazy,” Clipson says. “That was truly a case where reality was better than a made-up story.”

***

Shortly after midnight, on a warm summer night in 1968, a nimble Kaman UH-2A/B Seasprite launched off the destroyer Preble in the Gulf of Tonkin and flew along the coast of North Vietnam.

A few hours earlier, naval aviators John Holtzclaw and John Burns had ejected after their F-4J Phantom was hit by a missile. Still, LeRoy Cook, flying in the left seat as copilot of the helicopter, didn’t expect to be dispatched on a search-and-rescue operation.

“They’d never sent a helicopter in at night before,” Cook says, “so we were just waiting to hear, ‘Okay, turn around and come home.’ Instead, we were told, ‘You’re cleared to go feet dry,’ meaning we could turn inland. We had maps with little red dots where the known gun placements were, and we were right at Vinh [Son], which was one of the most protected cities in North Vietnam. So we thought, Oh, crap.”

Holtzclaw and Burns, who had broken several bones in his leg when he landed, had taken cover in jungle so thick that they could traverse it only on their hands and knees. As the UH-2A/B headed toward them, Cook saw something—possibly a missile—whoosh past, trailing sparks in the night sky. Pilot Clyde Lassen swooped down from 6,000 feet and landed on the edge of the jungle. Light from parachute flares deployed by other airplanes showed rice paddies and small huts nearby. Holtzclaw and Burns were on a ridge overlooking the clearing. “Come get us!” they radioed. “We can’t get out of here.”

Lassen decided to make a hoist pickup with a jungle penetrator at the end of a 200-foot cable. But the trees shrouding the downed aviators were taller than 200 feet, and because his engine was overstressed, Lassen had trouble holding a hover. So he peeled off to allow Cook to dump some fuel and lighten the load. Then Lassen returned and—using illumination from another set of parachute flares—snuggled down in between some trees to make sure the cable would reach the ground. That’s when the flares went out, blinding the helicopter crew and leaving Lassen without a visual reference point.

“You’re drifting right! You’re drifting right!” hoist operator Bruce Dallas shouted. In the process of correcting, one horizontal stabilizer clobbered a tree. The helicopter pitched down sharply before Lassen regained control. Shuddering as it flew, the Seasprite returned to the clearing where it had landed originally and the men waited for Holtzclaw and Burns. By now, the helicopter was dangerously low on fuel. “We’ll stay here until we have enough fuel to get feet wet,” Lassen said. “Then, if we have to, we’ll set it in the water.”

Right about this time, Holtzclaw saw figures rushing out of the brush. “I said, ‘We’re gone, Zeke,’ ” he recalls. “And with no discussion, I pushed him off this sort of cliff, and we went rolling down the side like tumbleweeds.” While Cook and crewman Don West laid down covering fire, Holtzclaw and Burns hustled into the helicopter. “Burns had a broken bone in his ankle, and he outran Holtzclaw to the aircraft,” Cook says.

Tracers and at least one missile went whizzing past the H-2 as Lassen raced for the water. “Jink this thing!” Holtzclaw yelled. “I don’t have the fuel to jink,” Lassen told him. In fact, the helicopter wouldn’t have made it home if the USS Jouett hadn’t steamed within three miles of the coast. (The Preble was still too far out to sea.) As it was, Lassen—who later received a Medal of Honor for his actions—dispensed with the usual landing procedure and simply crunched the helicopter down on the frigate. In the gas tank, less than five minutes of fuel remained.

***

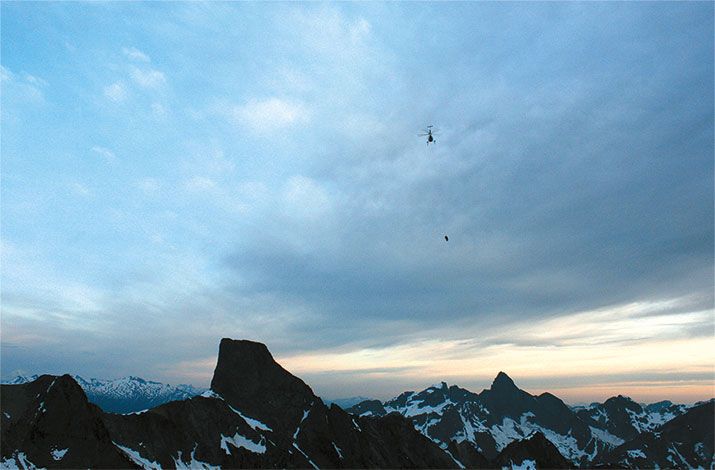

During a climb up Mount Terror in northwestern Washington in the summer of 2009, Steve Trent had fallen 60 feet, suffering a concussion, breaking his left femur, and shattering his right heel. Park Ranger Kevork Arackellian knew the rescue would be touch and go.

The rock face where Trent was anchored was very steep, so merely reaching him was going to be difficult, and lowering a litter to him would be time consuming. Oh, and bad weather was rolling in. “It was very clear that he was most likely not going to survive the night unless we got him out of there,” Arackellian says.

The National Park Service uses a search-and-rescue technique called short-haul. Instead of a rescuer being lowered with a winch, he’s attached to the bottom of the helicopter with a long, fixed length rope. The pilot then climbs, descends, and moves from side to side to position the rescuer as needed. This is reasonably straightforward when the terrain is open and flat. But in this case, the pilot would be dealing with unstable weather and a nearly vertical surface. And, in fact, the first pilot to assess the situation told Arackellian that the winds were too gusty for him to attempt a short-haul flight.

Enter Tony Reece, the owner of Hi Line Helicopters. Reece had more than 30 years of experience with long-line flying, using helicopters to help erect bridges or pour concrete and gravel trails, and his logbook already included about 400 search-and-rescues for the park service. His bird—a Hughes 500D with an upgraded engine—was small enough to work safely in tight quarters and powerful enough to hold steady in inclement conditions.

Reece flew to Mount Terror with Arackellian dangling from the end of a 100-foot rope, looking less like a park ranger than an airshow stuntman. At 6,600 feet, where Trent and his climbing partner, Jason Schilling, were waiting, winds were gusting from 15 to 25 mph.

Keeping one eye on the mountain and the other on his cargo, Reece eased Arackellian against the rock face and about 10 or 15 feet above Trent. Arackellian scrambled down to the injured climber and fought the wind before clipping Trent’s carabiner into the short-haul line. “I have to cut this rope,” he yelled at Schilling, referring to the lines anchoring Trent to the mountain. Arackellian tossed Schilling a bag full of bivy gear—food, water, sleeping bag. “There’s a radio in there,” he shouted. Then he, Trent, and Reece were gone. The actual rescue took less than one minute.

Reece short-hauled Trent and Arackellian eight frigid miles to the small town of Newhalem. But by the time they landed, the weather had closed in and there was no opportunity to go back and grab Schilling. He spent four supremely uncomfortable days and nights on the mountain. On the morning of the fifth day, Reece and Arackellian returned with the Hughes 500D and plucked Schilling off Mount Terror. Schilling and Trent made complete recoveries.

***

Ben Orrell vividly remembers his first briefing for the combat search-and-rescue that would earn him an Air Force Cross in 1972. “The commander took us into a room and said, ‘We’re not willing to send anybody in there unless it’s a volunteer mission, because we don’t think you’re going to come back out,’ ” he recalls.

The previous night, a Marine Corps A-6A Intruder had been shot down during a road reconnaissance mission over Laos. Although navigator/bombardier Scott Ketchie was—and remains—missing in action, pilot Clyde Smith had been located in the jungle. But he was surrounded by enemy troops, some of them so close he could hear them whispering as they looked for him. The spot where he was holed up was just a few miles from the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was well fortified with surface-to-air-missile sites and anti-aircraft batteries. “It was well known that the Laotians did not take prisoners,” says Orrell, “so we really needed to get this guy out before they got him.”

For two days, crews trying to prevent enemy soldiers from finding Smith flew over the area in F-4 Phantoms, F-105 Thunderchiefs, and A-1 Skyraiders, saturating it with ordnance. “Happiness was having a concussion lift me almost off the ground,” Smith says. Conditions were so perilous that the first two rescue missions were scrubbed. Finally, on the third day, two rescue teams were granted permission to go after Smith in Sikorsky HH-53s, the twin-engine workhorse known as the Super Jolly Green Giant. They were escorted by eight Douglas A-1 Skyraiders. Orrell headed to Smith’s position, while the second helicopter remained at the holding area as backup.

Orrell crossed the Ho Chi Minh Trail and his helicopter immediately started taking anti-aircraft fire. When he descended, hot, humid air caused the cockpit to fog up. As the crew frantically cleaned the windscreen, they received a radio call from the A-1 pilot leading the rescue: “Break right! Right! Right!” At an altitude of 200 feet, the flight skirted over a complex of armed bunkers. Orrell saw a round heading for his sternum hit the armor plating between his feet. But ramp gunner Sergeant Bill Brinson was hit in the knee. “Can you still shoot your gun?” Orrell asked him. When Brinson said he could, Orrell told his crew, “We’re going in.”

Smith ignited a smoke flare designed to establish his position for the helicopter. The tree canopy was so thick that Orrell couldn’t see the ground, but he hovered over the red smoke while flight engineer Bill Liles used an electric motor to lower the jungle penetrator—a cable with a collapsible seat at the end. What Orrell didn’t realize was that the smoke from Smith’s flare had gotten trapped in a gulley and drifted 100 to 150 yards away. The helicopter took ground fire as Orrell hovered. And hovered. And hovered. Still no sign of Smith. Finally, Orrell decided that Smith wasn’t going to make it. “We’re done,” he told his crew. “We’ve got to go. Pull it up.”

By this time, Smith had left the safety of his hiding spot, among the roots of an overturned tree, and begun sprinting toward the penetrator. When he reached it, instead of wasting time unsnapping the seat, he clipped his ejection harness directly to the cable. “Then, all of a sudden, I felt a whoop!” he says. “The next thing I know, I’m going up to the helo!” The only person more surprised than Smith was Orrell. “When we brought the forest penetrator up through the trees, he was there!” he says. Four decades later, he is still amazed.

Later, they found bullet holes in the rotor blades, fuselage, and external tanks.

Preston Lerner wrote about Hollywood’s aerodynamically challenged aircraft in the Oct./Nov. 2012 issue.