The Pilots of Mount McKinley

For 50 years, the world has reached the mountain on airplanes from one small town.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pilots-Mount-Mckinley-hero-2-631.jpg)

Veteran glacier pilot David Lee does not like what he sees out the windshield of his Cessna 185. He and his passengers—a team of German climbers anxious to start their attempt on Mount McKinley’s summit—are headed toward the base camp at 7,200 feet on the Kahiltna Glacier, a two-mile-wide river of snow-covered ice on the southern slope of the Alaska Range. In the single-engine, six-seat, dull red Cessna, Lee is watching clouds build and threaten to obscure the route through the mountains into the camp. He is tantalizingly close to his objective. Five minutes from now, if the weather were even slightly better, he’d be flying an approach he has flown thousands of times to a familiar patch of relatively level snow.

Reluctantly, Lee switches to company frequency, and reaches for the mike.

“Sheldon Base, One Echo Echo.”

At the Sheldon Air Service flight office, about 60 miles away in Talkeetna, Alaska, the unexpected radio call breaks the stillness.

Dispatcher Jody Fitzgerald responds, “One Echo Echo, Sheldon Base.”

Lee says, “We’re coming back.”

A round trip that produces no revenue is a tough decision, but in this moment Lee is providing what the client is really paying for: not just transportation, but experience and judgment as well. More than three decades of flying the Alaska Range has taught him there’s a point past which you don’t push the mountain.

Sheldon Air Service is one of a handful of aviation businesses that exist almost solely because of the allure of Mount McKinley. At 20,232 feet, it is the tallest mountain in North America, with a higher vertical rise from its base (18,000 feet) than Everest. In 2012, 1,223 climbers registered with the National Park Service; 498 achieved the summit. Six lost their lives in the attempt.

David Lee and the other high-time skiplane pilots working the frozen slopes of Denali (Alaskans call Mount McKinley by its native American name) occupy a tiny niche in aviation. There are fewer working commercial glacier pilots than there are astronauts who have flown on the International Space Station. The pioneers of the trade were self-reliant, minimally equipped adventurers whose scrapes, survivals, and disasters contributed to the legend of the Alaskan bush pilot. Today, the frontiersmen have given way to an organized, technology-enabled nature tourism industry. But the mountain hasn’t changed, and to survive flying there, today’s pilots need the same set of unique aeronautical skills refined by their forebears and the same ability to judge when conditions pose unacceptable risk.

***

Most air taxi services flying tourists to the mountain and supporting its climbers are based in Talkeetna. In few places is aviation as interwoven with local culture as it is in this small town. A small dirt airstrip, once Talkeetna’s only runway, begins one block below Main Street (though most air traffic today uses Talkeetna State Airport, on the town’s southeastern edge). In the historic Fairview Inn, built in 1923 and topped by a windsock, the walls are covered by photos of climbers and pilots in equal proportion. On one wall, a plaque carries the motto that has told the story of transportation in Alaska since the 1930s: “Fly an hour or walk a week.”

A short walk from the weather-worn Fairview, a community theater occupies what once was the hangar of the town’s most famous pilot. In the mythic history of Talkeetna, the late Don Sheldon is the Chuck Yeager of glacier flying. When he and partner Stub Morrison established Talkeetna Air Service in 1947, Denali had not yet become the international tourist magnet it is today. An inscription painted on the hangar wall facing the town, still barely legible, reflects the partnership’s original customer base: “Morrison & Sheldon, Registered Big Game Guides.”

Sheldon was a natural pilot, one of those rare beings who fly more by instinct and touch than by intellect. In 1982, fellow Talkeetna Air Service pilot Mike Fischer described Sheldon’s style in Reader’s Digest:

“He was a classic seat of the pants flier. But he was an atrocious theoretician. He had these outrageous theories on how an airplane worked. I often said ‘If he actually flew the way he talked about flying, he wouldn’t be able to talk about flying, because he wouldn’t be here.’ Still, he was an intuitive expert at extracting the last possible ounce of performance out of an airplane. He knew from experience what wouldn’t work.”

A biography of Sheldon, Wager with the Wind by James Greiner, is crammed with entertaining accounts of daring rescues, duels with the weather, demolished airframes, babies born en route to the hospital, and climbers making mountaineering history. Greiner and others who have written about mountain climbing in Alaska secured Sheldon’s reputation: a colorful, talkative personality brimming with confidence, who became a legend despite an atrocious flight safety record.

From the bountiful publicity surrounding Sheldon’s career, one wouldn’t suspect that there was another glacier pilot, just as skilled, operating from Talkeetna at the same time—an arch-rival whose conservative approach and introverted personality may not have been the best qualities for public relations, but whose sterling safety record established him as a master pilot.

***

Cliff Hudson arrived on the scene in 1948 to join his brother, who had established Hudson Air Service two years earlier. Where Sheldon was gregarious and regaled passengers with a running commentary on features of Alaskan terrain and wildlife, Hudson was circumspect and almost silent. Retired Air Force pilot Jim Okonek flew for Hudson before he bought his own Talkeetna flying business and recalls hearing a story from one of Hudson’s passengers about a sightseeing trip: “He said he had flown with Cliff years ago, and they had gone out for a very nice flight. And Cliff hadn’t said a word. They didn’t have the intercom. Cliff was the very last one to ever get an intercom. They had come back over Curry Ridge, and the black bear were out. And there at that point Cliff hollered at them ‘They’re eating berries now.’ That was all he said, the whole goddamn flight.”

Nor did Hudson value publicity. According to Doug Geeting, who also flew for Hudson’s company before he started his own, Hudson didn’t even list a phone number for the air service in the local phone book. The number was listed under “Cliff Hudson.” If you wanted to book a flight with him, you had to know him, or at least know of him. Yet Hudson established a reputation for supporting the locals that is still honored. In addition to landing climbing expeditions on the Denali glaciers, Hudson carried people, mail, and supplies to remote homesteads. Each year in May, the Talkeetna Chamber of Commerce holds a fly-in in his honor.

In the 1950s, even when nearby mining operations were hiring pilots to airlift supplies, small-town Talkeetna wasn’t big enough for two flying businesses headed by equally talented pilots. According to local lore, the rivalry became intensely personal. Adventure writer David Roberts offered a glimpse of it in the Reader’s Digest article: “After an incident in which Hudson alleged that Sheldon had buzzed his airplane in mid-air, the two pilots ended up in court on opposite sides of a nasty lawsuit. And once, when ‘the Rat,’ as Sheldon called [Hudson], refused to move his truck, which was blocking Sheldon’s airplane, the antipathy escalated into a fistfight at the local grocery store. Neither man ‘won’ the fight, say witnesses, but the store lost its candy case.”

At least once, the adversaries united against a common enemy: Alaska’s merciless weather. In February 1954, when severe turbulence ripped apart a U.S. Air Force C-47 flying over south central Alaska, both pilots helped with locating survivors. After Hudson spotted the crash site, he climbed into the back of Sheldon’s Super Cub, and the pair set out under a lowering overcast to rescue the crew. Sheldon dropped Hudson off and returned to base to alert the Air Force and mobilize an extraction. Hudson hiked in supplies to the survivors, built a fire, and stayed with them through the night. In Sheldon’s biography, the account of the rescue makes no mention of Hudson. Both pilots eventually received citations for exceptional service from the U.S. Air Force for their help; Sheldon, in 1959; Hudson, only after the efforts of two of the survivors, in 2000.

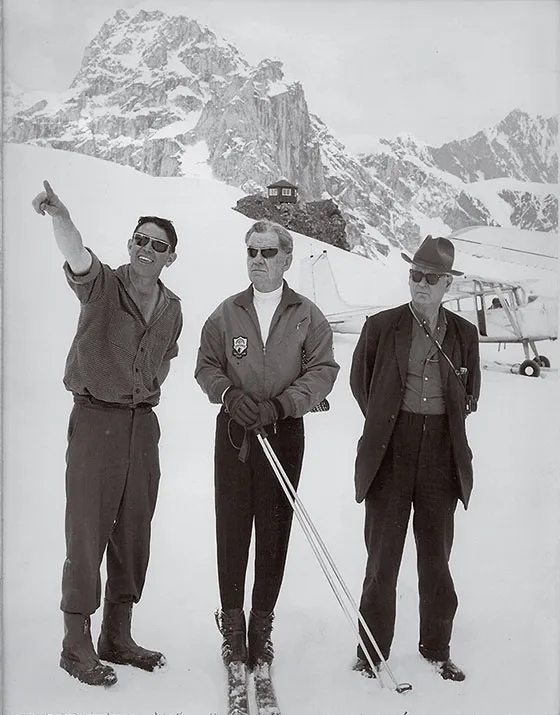

The man responsible for the direction that the air taxi services of Talkeetna would follow earned his living not as a pilot, but as a cartographer and mountaineer. Bradford Washburn had begun mapping Denali in the 1930s; in 1951, he resumed the effort. That year Washburn, who died in 2007, at 96, after 41 years at the helm of the Boston Museum of Science, pioneered the route to the summit followed by most climbers today.

Years earlier, Washburn had established the value of airplanes to Alaskan mountaineering. He heard about skiplane pioneer Bob Reeve, who had developed a method for landing on glaciers with flights to support the gold mines near Valdez. Washburn hired Reeve and his Fairchild 51 for a 1937 ascent of Mount Luciana, in the Canadian Yukon. When Washburn asked Reeve 15 years later to recommend a pilot who could fly him to glaciers in the Alaska Range, Reeve replied that he knew of “that kid [Sheldon], and he’s either crazy and is going to kill himself, or he’ll turn out to be one hell of a good pilot.” (In 1964, Sheldon married Reeve’s daughter Roberta.)

The collaboration with Washburn made Sheldon’s career. From the climber he learned the topography of the mountains, features that today’s glacier pilots know as well as they know the streets of Talkeetna: One Shot Pass, a V-shaped notch named by Sheldon that is a gateway to the Kahiltna Glacier; the West Buttress, Washburn’s route to the summit; Mount Hunter and to its south, a cluster of peaks climbers call Little Switzerland; the Root Canal, a tiny patch of level snow perched among escarpments known as Moose’s Tooth, Broken Tooth, and Bear Tooth.

The collaboration also forced Sheldon to develop techniques of glacier landing still in use today. First, overfly the landing area to look for crevasses or for drifts that could grab a ski. Second, as you approach, hold more power on than you would for a runway landing so that once you make contact with the snow, as the incline slows the aircraft, you’ll have enough momentum to turn to a downhill position for takeoff. Simple rules that take years of experience and highly developed senses to execute properly. Every landing is different, says Paul Roderick of Talkeetna Air Taxi, who has flown to the mountains more than 10,000 times since he began in 1991. “You can have a hundred different kinds of snow,” he says. “A lot of times, you can’t read it by air,” but only by what it feels like when the skis drag through it.

Doug Geeting, one of the most respected among Talkeetna glacier pilots, says that pilots also listen when they land:

“When you settle in to ground effect, you can hear—there is a sound difference.” Ground effect is the decrease in drag acting on an airplane’s wings when they are close to a surface. The difference in sound, says Geeting, is subtle, just noticeable if you know to listen for it, created by a change in airflow and amplified by the sound’s reflection off the surface on which the aircraft is about to land. In featureless terrain and flat light conditions, this sound, along with a slight reduction in the rate of descent, becomes an invaluable clue that the top of the glacier is near the bottom of the skis. Says Geeting: “You have to have faith in your ability to notice a rate- of-descent change [and] that you are going to notice a little sound difference when you get within 10 to 15 feet of the ground.”

In 1964, a Life magazine reporter described flying with Sheldon to the Kahiltna Glacier: “The winds are worse now, bouncing us all over the air. All around are somber rotten-looking cliffs that soar above us, and sharp, cleaverlike peaks that rise and rise. Soon Sheldon begins to pump a lever between our seats, lowering the retractable skis. The engine pounds and I see that our air speed has fallen from 140 miles per hour to 100. In front of us a wall of rock and ice suddenly fills the windshield. For a moment I think that we will surely bore right into it. Sheldon, using one hand and his teeth, is peeling an orange.”

***

It took several decades for Denali air support to evolve from the flights of two adventurers into an orderly industry. In January 1975, Don Sheldon died of cancer, at 53. That year, the Alaska Visitors Association formed its first marketing council, and by 1977 the total number of visitors to Alaska topped half a million a year. The number of climbers on Denali also surged, from 300 in 1975 to 900 in 1977. Today, the number is fairly steady at 1,200. Meanwhile, the glacier flying business got a new group of pilots.

One of the first of the new generation, Kitty Banner arrived in 1976 to find what she calls an odd group of characters. She compares Talkeetna to the 1966 movie King of Hearts, in which inmates escape from an insane asylum, take over the town, and “make a beautiful crazy sense of it all.” Working for pilot Jim Sharp, who had purchased Sheldon’s concession from his widow Roberta and renamed it Talkeetna Air Taxi, Banner began by flying fishermen on floatplane sorties to lakes near Talkeetna. In 1980, she bought her own air service concession with partner Kimble Forrest and named it K2 Aviation, branding the business for mountain climbers by its association with the famous peak in the Himalayas. Banner was a skilled marketer, and thanks to an intense off-season promotion effort, her firm gathered a plentiful clientele of European climbers, making K2 Aviation one of the most successful air taxi companies in Talkeetna.

In 1982, she described a typical day in the life of an Alaskan glacier pilot to a reporter at the Chicago Tribune: “You can start in the morning, just after dawn, and head off to Mt. McKinley carrying mountain climbers. ….Then you fly back to town, find you have another flight, hop into a float plane and fly out into the boonies to some old trapper’s cabin in the woolly north woods to deliver something he needs. You land on a lake near his cabin and there he is waiting for you. Then you come back, jump into a Super Cub, and fly off to a gravel bar in the middle of a river taking fishermen or hunters going out on an expedition.”

Today, pilots would add another activity to that lineup: Flightseeing has grown far more popular than ferrying climbers to base camp. When the weather is clear and “the mountain is out,” as the locals put it, Talkeetna Air Taxi and K2 Aviation run the big 1,000-horsepower turbine Otters on a half-dozen flights a day carrying cruise-ship tourists, who arrive at Talkeetna by the busload.

Banner and her partner sold K2 to Jim Okonek, and in the revolving-door nature of the trade, Banner went to work flying for him. Her last flying job in Alaska was for Doug Geeting at Geeting Aviation.

Geeting brought a new kind of experience to Alaska glacier flying. In the early 1970s, he worked with the flight test community at Edwards Air Force Base in California, where he ferried workers to remote dirt strips. Geeting says he was influenced by the test pilots’ dedication to methodology and their careful exploration of an airplane’s performance at all points in its envelope.

“Every glacier pilot ought to be able to tell you, within several knots, what the minimum maneuvering speed is of this airplane, at this altitude, at this weight, without thinking about it,” he says. Minimum maneuvering speed is the speed at which the airplane can bank 60 degrees for a 180-degree turn without loss of altitude—useful when poking around the narrow canyons and cul-de-sacs of the Alaska Range.

Geeting says the most important part of glacier flying technique is psychological. “You have a point on the approach phase I like to call the commitment point,” he says. “There is no go-around possibility, so get it out of your mind. That’s the key. Having it in your mindset that if you are going to do this, you have to commit yourself to do it and you have to stick to your plan.” To remind himself of the importance of that moment of judgment, Geeting maintained in most of his airplanes a little hand-lettered placard on the control yoke that said, “When in Doubt, Don’t.”

Today, K2 is run by Rust’s Flying Service, based at Lake Hood near Anchorage, and Geeting flies for them (see “Water World,” p. 54). In an irony lost on no one in Talkeetna, Don Sheldon’s daughter Holly purchased Cliff Hudson’s hangar and ramp space. With a National Park Service concession for flights to Denali, she and her husband, David Lee, opened Sheldon Air Service in 2010.

***

In any story about the mountains, the chief antagonist is the weather. Because of weather, David Lee postponed the delivery of his German clients to the glacier, and later in the season, he may have to postpone picking up Danish climbers Thomas and Anders Beckett. The brothers made the climb faster than they thought, and Lee got a call asking for a pick up days before he expected it, but he knows that supporting mountain climbers means you have to be ready to go when they call. Anyone arriving at base camp after climbing Denali will be at the limits of human endurance and badly want a shower and a bed.

In 1975, Cliff Hudson established a base camp manager on the Kahiltna Glacier to report the weather to pilots in Talkeetna and to organize the climbers for flights back to town. Today, the four Talkeetna air services share the expenses. Paul Roderick says that getting climbers off the mountain sometimes feels like the evacuation of Saigon. “If you didn’t have organization,” he says, “people would mob the airplane.” When camp manager Lisa Roderick (Paul’s sister) calls Lee’s cell phone to tell him that the Beckett brothers have arrived, exhausted, Lee is at a party celebrating his 50th birthday. When Roderick reports conditions at the camp, Lee determines that it’s open for flights but not by much and likely not for long.

Lee tells the guests to go on with the party, and he jumps in the pickup, runs to the hangar, fuels the 185 to the limit a takeoff at base camp will allow, pulls out all but two seats, and launches under the overcast, looking for a route to retrieve his climbers. With the welcome news, other Talkeetna operators also launch, hoping the window will remain open long enough to extract some of the mountaineers waiting for a lift. When base camp opens after an extended down spell, air traffic at Talkeetna Municipal resembles a fighter base scramble.

Thirty minutes later, Lee learns over the radio that conditions have changed again, and the camp has closed. As the other airplanes return to base, Lee considers his fuel and elects to linger to see if the weather changes yet again. His decision pays off: A small hole in the overcast drifts over the camp; when Roderick calls, Lee swoops in and lands. On the snow, the Becketts exchange high-fives with their fellow climbers.

But getting in and getting back out are two different things. Cloud still clogs the departure route. If it doesn’t lift, David Lee will spend his 50th birthday night in a spare sleeping bag in the base manager’s hut. It won’t be the first night he spends there.

Lee swings the Cessna into position for takeoff, instructs the brothers to load their gear, then walks to the edge of the takeoff area to evaluate the shifting conditions and consult with Roderick. Anders would later estimate it was a half-hour of consideration before Lee would suddenly turn and run toward the pair. “We knew then we would make it out,” Thomas says. “I’ll never forget that feeling.”

Minutes later Lee and his payload slid off the snow, turned left down the Kahiltna, and disappeared behind a canyon wall into another brief opening in the overcast. Like any wise pilot flying in Alaska, Lee, relying on experience, waited for the weather, knowing that the go/no-go decision would come, in the end, from the mountain.