10 Milestone Flights

You wouldn’t have wanted to be along on most of them.

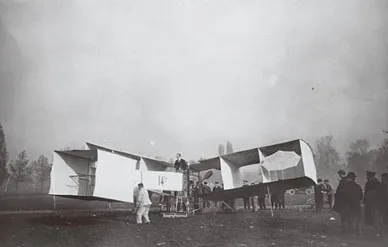

1. First powered flight in public

Fearing the attention of possible competitors, the Wrights tried to keep their achievement of powered flight secret for five years while they developed their Flyers further. Meanwhile, in France, Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont was feeling no such inhibitions. Santos-Dumont designed 14-bis, a pine-frame biplane with a 24-horsepower Antoinette motorboat engine, and he made several flights in it before crowds outside Paris. Technically, his first flight was on September 13, 1906, but it went only about 23 feet and reached an altitude—if that is the word—of two feet. The flight he made on October 23, which covered 197 feet at an altitude of about 10 feet, was his first substantial flight. It was also the first powered flight made anywhere outside of the United States, as well as the first powered flight by a non-Wright airplane.

A few portions of the Paris newspaper Le Figaro’s account: “[S]uddenly, Santos-Dumont points the end of the machine skyward, and the wheels visibly, unambiguously, leave the soil: the aeroplane flies. The whole crowd is stirred. Santos-Dumont seems to fly like some immense bird in a fairy tale…. Attempting to prolong the flight, he makes an adjustment to the nose of the craft, but—alas—in too brusque a movement! The aeroplane sinks.”

2. First carrier landing

A pilot for the Curtiss Aviation Company, Eugene Ely made the first landing of an airplane on the deck of a ship. The “carrier” used in the demonstration was the USS Pennsylvania, a battleship stationed in San Francisco Bay. The demonstration team had equipped the ship’s fantail with a wooden landing platform. Ely’s Curtiss model D pusher, the Albany Flyer, had no brakes; to halt it after landing, the team had equipped it with hooks that were to catch on one or more of 22 ropes that had been stretched across the landing platform and secured with sandbags.

On January 18, 1911, Ely took off from San Francisco’s Tanforan Field. He flew out over the bay, turned, and descended toward the Pennsylvania. On his first attempts, Ely was unable to land, but on the third, flying at about 40 mph, he accomplished what all naval aviators have had to master since: He flew his airplane low enough to get his hooks to catch. His caught on the last ropes. “This is the most important landing since the dove returned to the ark,” the captain of the Pennsylvania declared.

3. First armed air-to-air kill

World War I provided the first opportunity for one airplane to down another. On October 5, 1914, French pilot Joseph Frantz and mechanic/observer Louis Quénault were returning from a mission in a Voisin III biplane bomber. Their aircraft had just been outfitted with a Hotchkiss machine gun, and Quénault, sitting in front, had been instructed to try it out. At 6,500 feet over the French village of Jamoigne, he got his chance. A German Aviatik B.1, flown by Sergeant Wilhelm Schlichting, had been flying reconnaissance over French positions when Quénault spotted it below. He opened fire, and soon the Aviatik plummeted to earth. French troops watching from the ground burst into applause.

4. First aerial refueling

The trouble with airplanes is they have to come down, and not always when it’s convenient for the air crew. In 1923, under the command of Major Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, then commander of Rockwell Field in San Diego, the Army initiated a test program to determine whether it was possible to keep an airplane in the air by refueling as it flew.

On a June 27 flight over Rockwell Field, one de Havilland DH-4B, flown by Lieutenants Virgil Hines and Frank Seifert, dropped a 50-foot rubber hose down to a recipient DH-4, flown by Army Air Service Lieutenant Lowell H. Smith. In the rear seat of the second craft, crew member John Richter grabbed the hose with his hands, connected it to the fuel tank in his DH-4, and opened a valve in the hose. Air-toair refueling was born. The technique enabled the receiving craft to keep flying over Rockwell for six and a half hours (and, incidentally, to set a distance record—3,293 miles).

5. First transatlantic air crossing

Having made the first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight, Charles Lindbergh became the romantic favorite for the loneliness-of-the-long-distance-flier archetype. But aircraft had first crossed the Atlantic years earlier, and in a decidedly less lyrical team effort. During World War I, the U.S. Navy had commissioned Glenn Curtiss to build flying boats with enough range to guard U.S. ships in the Atlantic against German submarines. Curtiss built four, NC-1 through NC-4 (“NC” stood for “Navy-Curtiss”), but the war ended before the craft could enter service.

Eventually, the Navy decided to enter the NCs in a competition sponsored by newspaper publisher Alfred Harmsworth, a.k.a. Lord Northcliffe. The award: £10,000 for the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

On May 8, 1919, NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4, each with six crew members, took off from Rockaway Naval Air Station on Long Island, bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia. (NC-2 had been damaged and was grounded; it served as a source for spare parts for the other “Nancies,” as the Navy called the NCs.) On May 16, the three craft left Canada for the long, gray haul over the Atlantic. To help the effort, the Navy stationed ships across the ocean to serve as navigation aids.

As the NCs approached the Azores, islands located 600 miles from Portugal, the weather turned miserable—rainy and foggy. The crews of the NC-1 and NC-3 landed their craft on the sea to await clearer weather, but they sustained damage and were unable to take off. The NC-1 crew was picked up by a Greek steamer. NC-3 drifted over 200 miles before it got to the Azores.

NC-4 had better luck. On May 27, it finally landed in the Tagus River of Lisbon, Portugal. “We are safely on the other side of the pond,” Lieutenant Commander Albert Read radioed, a tad prosaically. “The job is finished.”

6. First flight on instruments

On the morning of September 24, 1929, at Mitchel Field in Long Island, New York, Army Air Corps Lieutenant James H. Doolittle set about the task of blinding himself. He sat under a canvas canopy that had been installed in the rear cockpit of a Consolidated NY2 Husky. His only source of illumination: an instrument on the control panel that gave off green light. Doolittle was preparing to make the world’s first flight without any recourse to the view through his windscreen. He would depend entirely on instruments—the turn-and-bank indicator, airspeed indicator, artificial horizon, directional gyro, barometric altimeter, and short-range landing beam system, plus a stopwatch.

Doolittle had wanted to make the blind flight alone, but the organization sponsoring the project, the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, insisted that a second pilot, Lieutenant Ben Kelsey, be in the open front cockpit, which had a duplicate set of controls, in case it was necessary to avert a mid-air collision, a theoretical danger on an instrument-only flight.

Doolittle took off. The flight extended 15 miles, during which he executed two 180-degree turns. In the landing, he used a short-range radio beacon system to home in on the runway, and the artificial horizon to keep his craft level. Copilot Kelsey never once had to use his duplicate controls. All in all, the flight was as uneventful as it was historic.

7. First jet flight

The first flight in a jet aircraft was made on August 27, 1939, by a German, Erich Warsitz. His airplane, a Heinkel He 178, was powered by an 838-pound-static-thrust Heinkel HeS38 turbojet engine, designed by Hans von Ohain. Wary of the engine, Warsitz carried a hammer to use in case he had to escape the cockpit.

He took off from the Heinkel Airfield in Marieneke, Germany, reached a speed of more than 400 mph, remained airborne for seven minutes, then landed. The engine’s only misbehavior: On takeoff, it sucked in a bird.

8. First Inflight Hijacking

Not all milestone flights are records to take pride in. The first inflight hijacking took place on July 16, 1948, when four Chinese passengers demanded control of a Cathay Pacific Consolidated Catalina OA-10 seaplane en route from Macao to Hong Kong. When the pilot refused to give in, the hijackers shot and killed him and his copilot. The pilot’s body fell on the control stick, putting the Catalina, Miss Macao, into a dive. The aircraft smashed into the sea off Macao, and 25 of the 26 people aboard were killed. The sole survivor was the hijackers’ leader.

9. First flight to break the sound barrier

No, it isn’t really a “barrier,” but something seemed to break on October 16, 1947, when U.S. Air Force test pilot Chuck Yeager became the first person to fly faster than the speed of sound. He was flying a rocket-powered Bell X-1 over Muroc Dry Lake in California when he passed Mach 1, “and in that moment,” reported Tom Wolfe in The Right Stuff, “on the ground, they heard a boom rock over the desert floor—just as the physicist Theodore von Kármán had predicted many years before.”

At that point, Yeager had reached an altitude of about 43,000 feet. The atmosphere was so thin it held almost no light-reflecting dust. “The sky turned a deep purple,” wrote Wolfe, “and all at once the stars and moon came out—and the sun shone at the same time….[Yeager] was simply looking out into space.” The X-1’s foray beyond Mach 1 lasted a little more than 20 seconds. The fame Yeager earned for the flight: 55 years and still going strong.

10. First helicopter hoist rescue

Texaco oil barge 397 was in trouble. It was November 28, 1945, and the barge, with two men on board, had broken away from a tanker off Bridgeport Harbor, Connecticut, and was drifting away. After a few hours, the barge washed up on Penfield Reef, off the town of Fairfield.

The men on the barge, Joseph Pawlik and Steven Penninger, set off flares. Spotting them, a group of townspeople gathered on a nearby beach to watch the hapless barge as it was battered by agitated waves. One person in the crowd had an idea: Sikorsky Aircraft was in nearby Bridgeport; perhaps a helicopter from there could be recruited to help. Someone put in a call to the plant.

Sikorsky test pilot (and Igor Sikorsky’s cousin) Jimmy Viner and a friend, Jackson E. Beighle, climbed into a helicopter and quickly flew to the barge. When the pilots saw the problem, they returned to the plant and got into an R-5 that had been recently equipped with a hoist.

Once back over the barge, they dropped a note to the stranded men, telling them a harness was about to be dropped. Penninger donned the harness and was hoisted up quickly, but because the R-5’s cabin was so small, he had to be flown back while hanging half out of the craft, clinging to Beighle. Pawlik had an even worse time: As he was being lifted, the hoist stalled, so he had to be flown while hanging 30 feet below the helicopter, battered by high winds.

At the beach, a news photographer got a gripping shot of Pawlik dangling; the next day, it appeared in newspapers all over the country. From that day on, the helicopter enjoyed a reputation as the Good Samaritan of aircraft.