Art From the WWI Trenches

Scenes from the Great War come to life a century after the Armistice.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/c6/0cc62f6e-dea9-4f9d-81d9-503a5446d601/16f_am2017_af26126townsend-_crop2.jpg)

Of the more than two million U.S. troops who served in the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during World War I, a handful were professional artists sent to chronicle the experience of battle. Hearing artillery shells screaming overhead while sketching a scene was an unnerving affair: “My poor heart was trying to beat its way out of its weakening cage,” artist Harry Everett Townsend wrote in his diary shortly after arriving in France. “Go on I could not.... Here to do the war and showing yellow, it seemed!”

The artists stayed with the troops for nine months, and they had no restrictions on what they could paint or draw. By the end of their tour, they had produced more than 700 artworks. At war’s end, the War Department transferred about 500 of these to the Smithsonian Institution. Now, for the first time in nearly a century, art from that collection is on display in a new exhibition titled “Artist Soldiers: Artistic Expression in the First World War.” The exhibition of 54 works was jointly produced with the National Museum of American History, and is on view at the National Air and Space Museum through November 11, 2018, the 100th anniversary of the Armistice.

“Before World War I, war art depicted heroic military leaders and romanticized battles, and it was done long after the fact and far from the battlefield,” says chief curator Peter Jakab. “The first world war marked a turning point in the appearance of artwork intended to capture the moment in a realistic way by firsthand participants.”

The artists were chosen by illustrator and painter Charles Dana Gibson (creator of the Gibson Girl, an illustration of an idealized American woman of the 1890s); the first painter he approached was his friend Ernest Clifford Peixotto, who had tried to join a camouflage unit in the Army’s Corps of Engineers but was rejected because of his age (he was 49). Gibson was part of the Division of Pictorial Publicity, a group tasked with generating art that supported the war effort. And because British and French armed forces had already recruited artists to work alongside their soldiers, the U.S. War Department wanted official artists there as well. But some American officers remained skeptical of the enterprise. According to historian Alfred E. Cornebise, while Peixotto was sketching members of the 32nd Division in the Haute Alsace, he was approached by a lieutenant colonel who asked what he was doing. Peixotto displayed his pass and explained the program. “My God!” the colonel exclaimed. “As if we didn’t have enough trouble! They send us artists.” When Peixotto reminded him that France and United Kingdom had already sent artists to accompany the troops, the colonel sniffed, “That is why they are not winning the war.”

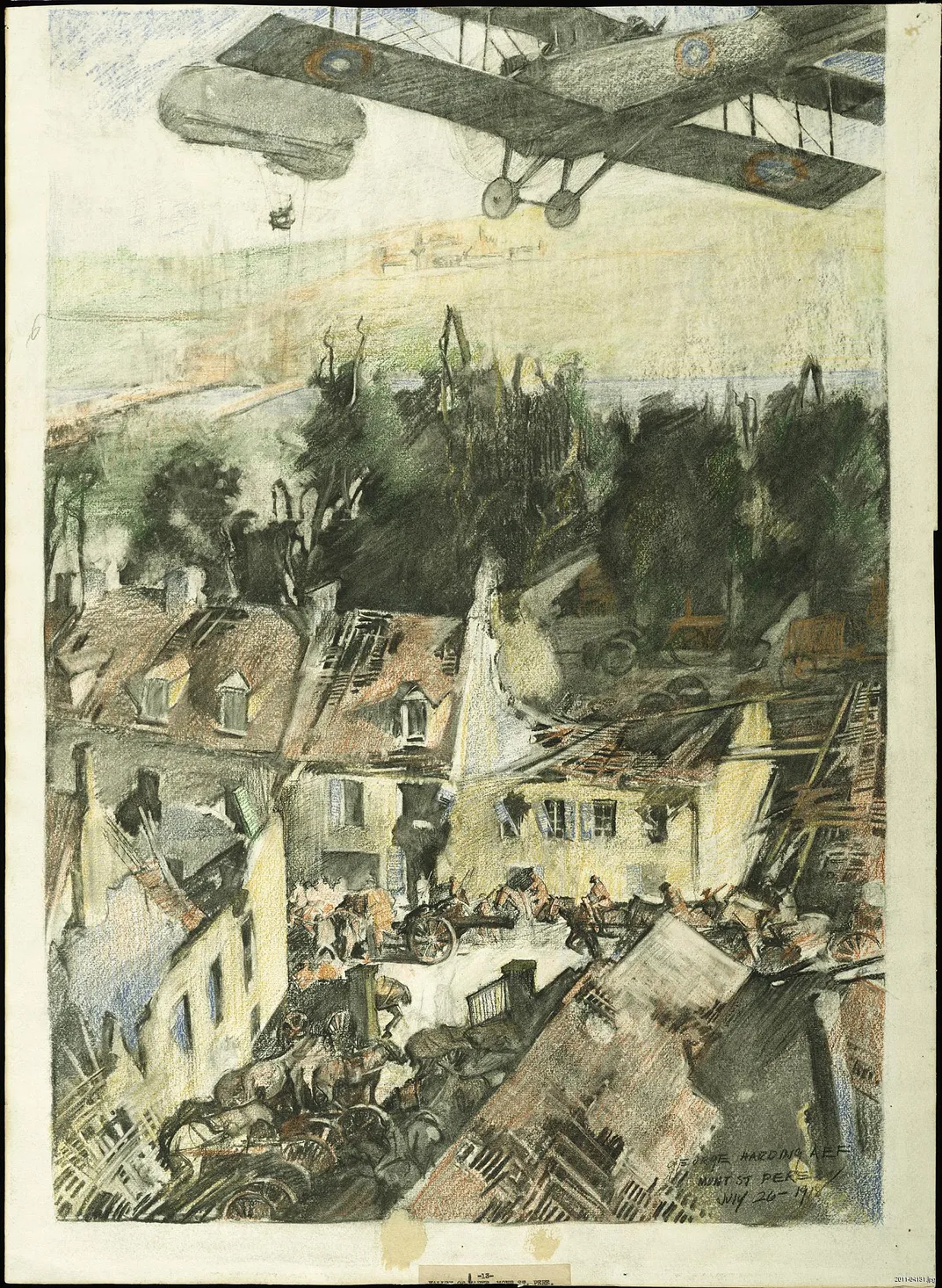

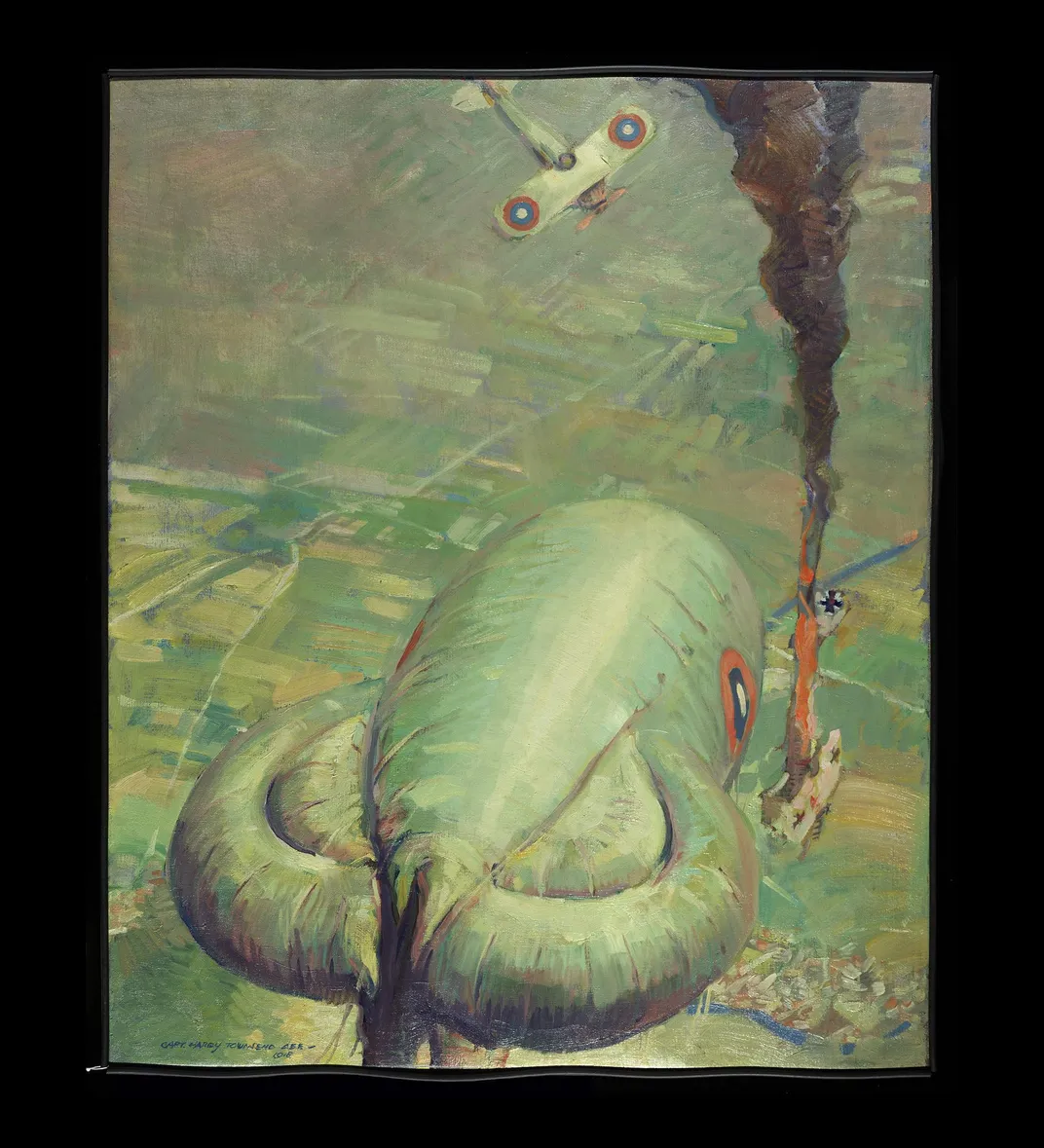

Six of the artists were magazine illustrators—among them, Harry Everett Townsend, a regular contributor to Harper’s and Scribner’s magazines. Peixotto was a fine artist, and J. André Smith, an architect. The artists developed their own specialties, which fell broadly into two approaches: In one, they chronicled troop movements and life in the trenches; in the other, they focused on the landscape and the AEF’s broader activities. Townsend, for example, focused on aerial scenes; after the war ended, he made detailed studies of captured German aircraft.

Another illustrator, William James Aylward, best known for his pre-war advertising art for steamship companies, gravitated toward the “sea-stuff,” covering, among other subjects, troops at various ports.

George Harding—the only painter in the group to serve as a combat artist in both world wars—was known for his realism, while Harvey Dunn created emotionally charged portraits of the troops.

In addition to works by professional artists, the exhibit features art created by soldiers themselves. Some of the most haunting are carvings made in underground limestone quarries that provided sanctuary from the war raging above. The walls of these quarries served as canvases for the German, French, British, and American soldiers sheltering within. For the past five years, Jeff Gusky (a physician, explorer, and National Geographic photographer) has photographed the quarries—all of which are on private property—and tried to connect the artists who made the elaborate carvings to their living descendants. Twenty-nine of Gusky’s images are featured in the exhibition. (His photographs and re-discovery of the carvings are also the subject of a Smithsonian Channel film.)

“The participants of World War I can only speak to us now from the archival record and the material culture they left behind,” says Jakab. Fortunately, their voices are eloquent.