Cornelia Fort Wanted to Fly in Combat, But Not in a Civilian Airplane Against the Japanese at Pearl Harbor

How a vintage Interstate Cadet trainer led a modern airshow pilot on a journey to find a kindred spirit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pearl-Harbor-collage-FLASH.jpg)

When you collect a certain kind of airplane, after a while, those airplanes seek you out. That is more or less is what happened to Kent Pietsch. Pietsch, 54, has repeatedly been charmed by a high-wing, low-power, two-place-cabin, tail-dragging, primary trainer called the Interstate Cadet. It is not a famous design. Even in its day, the Cadet was often mistaken for the far more numerous Piper or Taylorcraft Cubs. The Cadet’s heyday was 1941 and 1942, the brief period from just before America entered World War II until just after. Smack in the middle came the attack on Pearl Harbor, in which one Interstate Cadet played a brief, minor, but memorable role. It was this Cadet that, seven decades later, began to possess Kent Pietsch.

Pietsch (pronounced “peach”) grew up on a farm about nine miles south of Minot, North Dakota, part of a clan of flying Pietschs. His father, Al, formed the Pietsch Flying Service, which is still crop-dusting and selling, servicing, and restoring aircraft after 56 years. In 1968, the family expanded its flying ventures, debuting Pietsch Air Shows.

Pietsch was still a teenager when he bought his first Interstate, a tired flight school veteran. He had been working in the family hangar since grade school, trading work for lessons and soloing at 16. In high school, he began drawing up a dream airplane—a hotshot, mid-wing aerobat—but he couldn’t get the wings right. That led him to a fat volume on airfoils, and turned him into a teenage airfoil fancier. Looking out the hangar door one day at Uncle Leonard’s weatherbeaten Cadet, Pietsch realized that the Interstate was sporting his ideal airfoil. He ran out to measure, then ran back inside to buy N37428 from his uncle. He’s had it ever since. When he joined the family airshow, Pietsch built his act around the Cadet’s forgiving airfoil.

Pietsch is a big man, well over six feet tall. (Part of the joke in his act is Big Man climbing out of Small Airplane.) He doesn’t go for the costumey flightsuits most show pilots wear. His wardrobe is jeans and a T-shirt advertising his sponsor’s Jelly Belly candy.

Pietsch has several routines. He flies a show-stopping act in which he lands a Cadet on top of a galloping recreational vehicle that carries on its roof a tiny “runway.” He also has a gentler but no less impressive performance. Call it his energy management act. At 6,500 feet Pietsch cuts the engine, then rolls, loops, glides, swoops, and dances his way down, landing so precisely that his Cadet comes to a stop with its motionless prop spinner kissing the palm of the airshow announcer, who has planted himself with seeming nonchalance on the runway. Then the Big Man hops out of the tiny Cadet for a bow. It’s a routine that combines showmanship, comedy, suspense, and a lesson in aeronautics.

Today, Pietsch has four Cadets, plus choice parts. One, N37266, came from a collection of seven more or less separate Cadets that an Ohio aficionado was disposing of. He had seen Pietsch fly a Cadet routine at the Florida Sun ’n Fun Air Show and tracked him down. Pietsch was not in the least interested. He had more than enough Cadets for his act, plus a pair of Waco Taperwings, open-cockpit biplanes he was reconstructing.

The Ohio owner talked up his wares. One of the Cadets, he said, had been in a Honolulu flight school the day Pearl Harbor was attacked.

That caught Pietsch’s attention.

For 28 years, Pietsch had flown for the airlines (he retired from Northwest in 2007). On his 24-hour airline layovers in Honolulu, he had become fascinated by Pearl Harbor history, especially after taking a tour of the USS Arizona Memorial led by Pearl Harbor survivor Richard Fiske. In 1991, Pietsch was flying for what was still Northwest Airlines as a DC-10 copilot on the run between Fukuoka, Japan, and Honolulu, Hawaii. On December 5, he had been westbound, Hawaii to Japan. Word came to the cockpit that one of the passengers was Zenji Abe, an elderly businessman who had been a Japanese dive-bomber pilot in the second-wave attack on Pearl. A deeply patriotic man, Pietsch went back on his break just to stare at this ancient enemy, only to be charmed by Abe, who had become a promoter of peace. “At first I wouldn’t even sit down with him,” Pietsch remembers. “I just perched on the armrest, but then we got talking and it was all right.”

Two days later, Pietsch was on an early morning approach to Honolulu International, 50 years almost to the minute from the first attack. “I think it was 8:14 in the morning,” he recalls. “We were coming Fukuoka to Hawaii on basically the same route as they [the Imperial Navy] took, only they came north of the mountain and we were coming south of it. The sun was shining through cloud and you could see the rising sun. It was unbelievable. We went right by the Arizona Memorial and I just felt a chill.”

After landing, Pietsch checked into his layover hotel and was getting ready to go to sleep when the room was rocked by the roar of military aircraft. He threw open the curtain to see a B-52 tear by at eye level, making a low tribute pass over the Punchbowl military cemetery. Pietsch switched on the TV news and saw footage of Zenji Abe hugging Richard Fiske at an earlier ceremony.

There was a message here about Pearl Harbor, Pietsch decided.

The Cadet the Ohio collector was offering was said to be flying over Hawaii at the time of the Japanese attacks. Pietsch was stunned: This might be the most famous Interstate Cadet ever made.

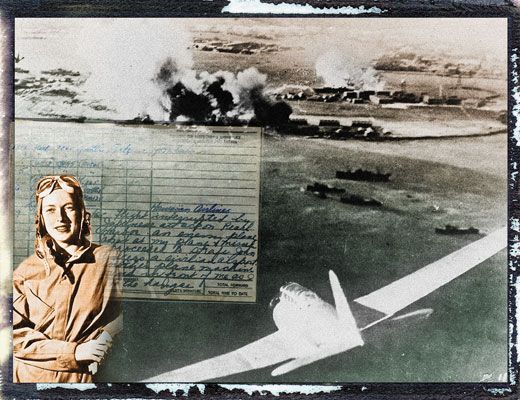

On December 7, 1941, an instructor and her student had taken a Cadet up over Hawaii for a routine lesson. The instructor was Cornelia Fort, 23, the eldest daughter in a wealthy Nashville family. Fort had shaken off her fate as a pillar of high society to become a pilot, and was teaching for a flight school based at Honolulu’s civilian John Rodgers Airport. Fort and her early-bird student, a military worker remembered today only by his last name—Suomala—were practicing touch-and-gos. Less than three miles to the northwest, Pearl Harbor and the U.S. fleet were visible, drowsing in the Sunday morning sunlight. Just before 8 a.m., Fort caught the flash of an airplane coming in from the sea. She was annoyed, then alarmed. The silver airplane, well outside the usual military zone, was heading low and straight for the Cadet.

Fort grabbed the stick from her student, slammed the throttle forward, and climbed desperately. The military intruder passed so close below them that its engine violently rattled the Cadet’s windows. That’s when Fort recognized the rising-sun insignia on its wings. Japanese bombers were pouring in from the northwest, and smoke was rising from Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese bombers were so intent on spotting their targets, most probably never saw the Cadet. One of the passing attackers did take a shot at it, but Fort quickly put the Cadet down at John Rodgers Airport. She and her student jumped out and ran for their lives as a Japanese fighter swooped through on a strafing run that shredded another trainer and killed the instructor.

Fort eventually escaped Hawaii. She was determined to get into the flying war effort on the mainland and show what was possible for women pilots, at a time when neither the military nor the general public took them seriously. She succeeded, but at great cost. In September 1942, she was one of the first 25 female pilots accepted into government service as part of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Service (WAFS). It was the forerunner of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) program, which in August 1943 would absorb the WAFS. Fort didn’t live to see that day. She was killed in March 1943 while delivering a new BT-13 trainer to an Army base in Texas. She was 24, and the first woman pilot to die on war duty in American history.

Fort’s Pearl Harbor escape had been widely recounted by newspapers in 1942, broadcast by Fort herself on the family’s Nashville radio station, and reported in her own words posthumously in the June 1943 Woman’s Home Companion magazine. By the 1960s, Fort’s flying lesson was a standard anecdote in popular histories of Pearl Harbor, and it was recounted, loosely, in the 1970 movie Tora, Tora, Tora. In the film, Fort, who was young, dark-haired, and thin, was played by a matronly, middle-aged actress in blonde curls. More critically, Fort’s closed-cabin Interstate Cadet monoplane was played by an open-cockpit Stearman Kaydet biplane, a gaffe that still galls aviation historians and Cadet collectors.

Today, the job of keeping Fort’s story fresh falls to Dudley Fort Jr., a retired Tennessee surgeon, avid pilot, and Fort’s nephew, and his cousin Chloe Frierson Fort. Through them, Fort’s story (and her papers, memorabilia, and anecdotes) caught the attention of Rob Simbeck, a Nashville writer who in 1999 published a wonderfully researched biography, Daughter of the Air.

Dr. Fort has clear memories of his glamorous aunt. He was almost seven, he recalls, when in February 1943 she came through Atlanta on a ferry flight and stopped to see his father, Dudley Fort Sr., the youngest of Fort’s three older brothers. “My father brought her to the house,” Dr. Fort recalls. “He had promised that she would bring her parachute for us to see, but she had left it in the airplane. What a disappointment. She brought my brother and me a Dick Tracy cap pistol, which we were only allowed to use under supervision.”

In Dr. Fort’s telling, Aunt Cornelia emerges as a feisty, very modern woman who drank scotch, smoked cigarettes, and fought with Dr. Fort’s father over politics, religion, and whether any member of the Fort family, let alone a woman, should be flying when their father (also a physician) had been so against it. In the 1920s, the first Dr. Fort had summoned his three sons into his study to take an oath that they would never fly. Soon after her father’s death, in 1940, Cornelia announced that, because she had been too young and a girl, she was exempt from the Fort family oath. She then revealed that she’d been taking flying lessons.

Also unburdened by the oath, the current Dr. Fort is today the enthusiastic owner of an Aermacchi SF.260 aerobatic and military trainer, which he considers the ultimate light aircraft. So he understands how a certain airplane can take hold of the imagination. When he heard last spring that an airshow pilot from North Dakota had bought an Interstate Cadet, believing it could be Cornelia’s, he wished the man well. But he could not verify that the airplane was indeed his aunt’s.

Last April the Hawaiian Cadet (well, its pieces) arrived in North Dakota. The logbooks that came with it went back only to the mid-1950s. So Pietsch did the next best thing: He got a disk containing all the data that the Federal Aviation Administration and its forerunners had collected on N37266. He learned that the airplane had been manufactured at Interstate’s El Segundo plant (now somewhere under Los Angeles International Airport) on June 9, 1941, and sold 21 days later to Andrew Flying Service of John Rodgers Airport, Honolulu, T.H. (Territory of Hawaii). On July 30, 1941, Olen Andrew, the proprietor of the flying service, sold N37266 to the nine partners of the Underground Flying Club at John Rodgers. So the setup for N37266 was perfect: a club aircraft parked at a flying school where it could earn some of its keep as a trainer for the proprietor’s Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) program. In September 1941, Andrew hired Cornelia Fort as a CPT instructor.

N37266 did not appear in the government records again until July 4, 1946, when the head of the aviation trades program at Honolulu Vocational School filed an Aircraft Inspection Report detailing a long list of repairs and manufacturer’s updates, concluding with the typed remark, “Aircraft has been in storage since December 1941.” (Nearly all private aircraft in Hawaii were grounded after the December 7 attack.)

The Underground Flying Club held onto N37266, flying it for the next 25 years. By 1971, the club had dwindled to two members. The airplane finally passed to a series of private owners in and around Honolulu. The last airworthiness application was dated 1973; in 1979, N37266 was sold in Honolulu for the last time. A few months later, it was registered in Newark, Delaware. From there it went to buyers in Texas, Arizona, Ohio, and now North Dakota.

When the airplane arrived in Minot, the city was sodden. It had been a wet spring, and the Souris River was rising, every day creeping closer to Pietsch’s airstrip and hangar. Pietsch started a small sandbag dike around the strip. It kept raining. By early May, he and an airplane buddy, Larry Eide, had a sandbag wall as high as their heads. By late May, with no sign of the river receding, Pietsch had flown out his flyable airplanes. In June, the water breached the dike, flooding his hangar to the rafters.

In mid-June, I rented a Hyundai and drove to Minot to check out N37266. Despite the inconclusive paperwork, Pietsch was now calling his purchase “Cornelia’s airplane.”

“Cornelia was right there on the forefront,” Pietsch told me later. “That was the start. That was the minute when it went from being a calm Sunday morning just like any other—then boom—it’s a world war in which millions of people died. And this airplane was there.”

Pietsch, Eide, and restorer Tim Talen wrestled the bare airframe, wings, and many boxes of parts onto Talen’s flatbed trailer, which Talen would drive to his shop in Jasper, Oregon. There, he would administer a full-bore, museum-quality restoration. Talen, who had earned a master’s degree in history before turning to antique airplanes, is the unofficial dean of Interstate Cadet studies. While the three men worked, Talen gave impromptu talks on how to recognize factory welds, how Interstate redesigned the original tail to gain 50 pounds of carrying capacity, and the mediocre performance of the Cadet’s military version, the L-6.

Interstate Cadets came into his life on a fluke, Talen explained. As a teenager, he’d hung around a small airport near his home in Chico, California, picking up enough of the rudiments of dope and fabric work to earn a few bucks. Noting his skill with wood and fabric, a customer offered him a set of wings off an unknown airplane. They turned out to be Cadet wings. Cleaned up and advertised in a western aviation newspaper, they fetched $500 from a grateful priest in Portland, Oregon, who dispatched them to a Catholic mission in Brazil that was flying Interstates. After that, Talen kept an eye out for Interstates. These days Interstates appear to return the favor, seeming to migrate toward Jasper, Oregon.

“The Interstate was the first aircraft that I got enthused about restoring to some sort of authentic condition,” Talen says. “Every one I’ve looked at since has given me another clue or tells me something that I didn’t know before about what it looked like originally.”

Compared to other trainers in the early 1940s, Talen says, the Interstate turned in better performance. “I’m sure all the Aeronca and Piper lovers would say I’m crazy, but I’ve flown them all. The Interstate is just a notch above. But it’s not brain surgery to figure out why. The Interstate came later on the market than these others, so it benefited from experience and from good design and good engineering. It shows up in the aerodynamics. It’s just a superior flying airplane.”

The men finished loading the parts onto Talen’s truck, and off N37266 went to regain a 1941 appearance. The rain was still coming down, and the Souris ran slate gray to the horizon.

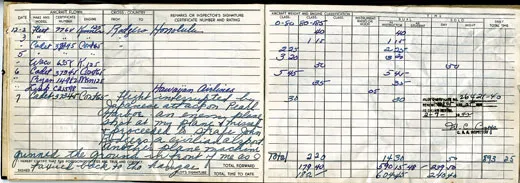

It was just after THat when the smoking gun turned up. In June, Dr. Fort realized that he could find the serial and tail numbers of his aunt’s Cadet. The Texas Woman’s University Libraries owns a group of photographs on the WASP, and among them was a scan of “page 13 left” of Cornelia Fort’s logbook, covering the first week of December. The scan was on the library’s Web site. Cornelia had flown the same Cadet on four occasions, and the entry for 12-7-41 read:

Cadet, 37345, Cont. 65 [Continental 65-horsepower engine]—Flight interrupted by Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. An enemy airplane shot at my airplane and missed and proceeded to strafe John Rodgers, a civilian airport. Another airplane machine-gunned the ground in front of me as I taxied back to the hangar.

Fort’s Cadet was N37345, not Pietsch’s N37266.

When he got the news, Pietsch was remarkably philosophical. Maybe he had a new perspective; on June 25, the Souris River breached Pietsch’s last defenses and flooded his house. The contents and the airplanes had been moved in time, but the interior would have to be gutted: The sheetrock was soaked.

Today, Pietsch believes that even if Fort had not flown it, N37266 must have been at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, perhaps sitting unharmed in a hangar at John Rodgers. Talen continued reconstruction of the “wrong” Cadet, right down to its original cables, brakes, and linen wing covering. As of press time, the fuselage and wings were finished; the engine had yet to be installed.

Once the Cadet is airworthy, Pietsch plans two debuts for it: The first is a flight this December 7, the 70th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack. Dr. Fort will fly the airplane; so far, a place has not been arranged. Pietsch also plans an airshow on the 4th of July, 2012, at the Minot International Airport to benefit area residents who were flooded. Along with the Cadet, the show will feature the Royal Canadian Air Force Snowbirds, a B-25, a P-40, a Mustang, and a Japanese Zero. The Zero and the Cadet will reenact Cornelia Fort’s Pearl Harbor flight.

There is a final mystery within the mystery: Pietsch has discovered that he might have owned Fort’s real Cadet all along. In his frantic transfer of airplane parts to higher ground, Pietsch had a quick look at a Cadet fuselage he had picked up in Texas years ago. It came without an aircraft registration number, but stamped on the metal was 188, the serial number listed for N37345.

Pietsch got the government records for N37345. There is no evidence that connects this Cadet with Hawaii, he says. Interstate had manufactured it and certified it airworthy on October 14, 1941, and sold it three days later to Judd Goodrich of North Hollywood, California, who was officially registered as the new owner on December 27, 1941. If Fort had flown it on December 7, someone would have had to crate it up and ship it back to Los Angeles immediately afterward. But in the days after the Pearl Harbor attack, getting out of Hawaii, for civilians and civilian airplanes, was next to impossible. Fort herself, even with family connections, couldn’t get back for nearly three months. The only other explanation is that Goodrich bought the Cadet at the end of 1941 but didn’t take possession of it until later.

The next reference in government records is a modification approval Goodrich got for installing two new antennas on September 19, 1942, in Tucson, Arizona. Two months later, on November 21, Goodrich sold N37345 to PT Air Service of Hayes, Kansas, where it began a short, unlucky life. From the repair certifications, Pietsch figures N37345 crashed in 1944 and again in 1955. Its registration lapsed soon after.

Why does it matter if this Interstate Cadet is the one that Fort flew over Pearl Harbor 70 years ago, and if the other was a sister ship that survived on the ground? Time thins out human witnesses, and to fully appreciate great events, we need historic objects. The horse that General Phil Sheridan rode to the 1864 Battle of Winchester stands stuffed in the Smithsonian; to look upon that genuine warhorse is to catch a whiff of Civil War gunsmoke. Anything else would be just a stuffed horse.

In this case, though, perhaps the artifact is less important, and the mystery can go unsolved. Fort was a talented writer who captured both the prosaic and poetic sides of flying in the early 1940s. Six weeks after surviving the horrors of Pearl Harbor, she wrote a strange, eerily past-tense letter home to her mother: “I dearly loved the airports, little and big. I loved the sky and the airplanes, and yet, best of all I loved the flying.” At the end, she wrote, “I was happiest in the sky ⎯at dawn when the quietness of the air was like a caress, when the noon sun beat down, and at dusk when the sky was drenched with the fading light.” Fort’s storytelling is powerful enough to carry us back to a different flying world before December 7, 1941, and to the new and crueler world just after.

John Fleischman is a frequent contributor.