Across the Divide in 1911

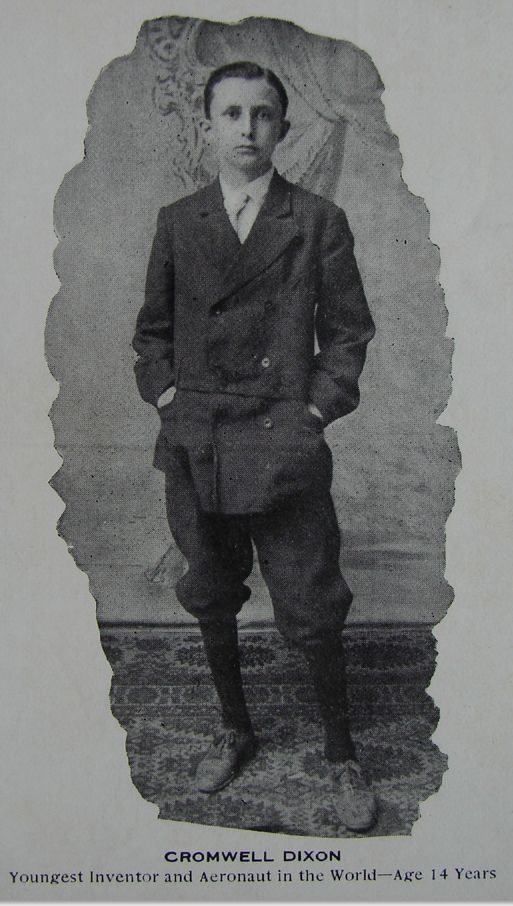

A new biography details the exploits of teenage aviation pioneer Cromwell Dixon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cromwell-631-mar08.jpg)

Over the past ten years I have launched my paraglider dozens of times from the top of the Continental Divide west of Helena, Montana, adjacent to the Cromwell Dixon campground. At 6,324 feet, this is the lowest point on the entire Divide, which stretches from Mexico to Canada. It's also the place where, on September 30, 1911, Dixon, at age 19, became the first person to fly over the Rocky Mountains. That same day, he was awarded a $10,000 prize from Louis Hill, president of the Great Northern Railway.

I can imagine Dixon's flight from the Helena Fairgrounds about eight miles east of the Divide. Gaining altitude above the gently rising Ten-Mile Valley, he would have faced a 1,600-foot wall of timbered slopes that thins out into tree-lined pasture at the top. What's harder to imagine is how this teenager had the pluck and competence to attempt what turned out to be his crowning achievement.

A St. Louis. Carried away by increasing wind speed, 1,500 feet in the air, Dixon made an in-flight repair to a chain drive that had jumped a sprocket. He got blown 12 miles off course and forced a landing on the east side of the Mississippi.

Dixon subsequently met Glenn Curtiss, who taught him to fly aeroplanes at a time when aviators were plain lucky to live through their experiments in flight. At age 17 he was the youngest licensed pilot and, arguably, the best exhibition pilot in the country.

Two years later, few would have disputed that claim. Piloting the Curtiss-built biplane, Little Hummingbird, Dixon conquered the Continental Divide. Two days after collecting his prize money, Dixon died, moments after taking off at an airshow in Spokane, Washington. The air was hot and thin, and Dixon's airplane took a long time to get airborne. He probably ran into a thermal that was building over the waste ground just north of the field. He naively banked just as he caught the cool downdraft at the edge of the column of rising air. Several hundred horrified spectators saw him go down.

Witnesses who were less than 100 yards from the crash site said the biplane tipped almost perpendicular and fell 150 feet, with Dixon vainly wrestling the wheel and yelling "Fly, fly!" and "Here I go, here I go!" Ironically, his Curtiss crumpled into the Great Northern Railway right-of-way.

Cromwell Dixon's tragically short life story is a tale of pure courage and skill that biographer Kidston handles with fondness, empathy, and an historian's reverence for detail.

Tom Harpole, a frequent contributor to Air & Space, lives in Avon, Montana.