The Birdman of Topeka

By 1912, Albin Longren was building better airplanes than the Wrights and Curtiss.

:focal(1615x685:1616x686)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/8e/448ef1a5-f8fc-48a2-8f42-ec45c8d1905e/longren_on_bike.jpg)

Albin Kasper “A.K.” Longren didn’t tinker with airplanes until 1910, the year a Curtiss pusher plane flew into Topeka, Kansas, not far from his hometown of Leonardville, for a public demonstration flight. The plane crashed, and the pilot gave Longren the chance to help repair it. He finished the job resolved to build his own.

Longren’s restive genius eventually both spurred and spoiled his legacy as an aviation pioneer. He helped shape the early airplane industry, designing and building state-of-the-art airplanes in Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. He also played a chief role in the U.S. government’s first airplane development center.Yet in the words of one Kansas aviation writer, Longren eventually “wandered off into an almost anonymous life,” robbing himself of his rightful place among the pioneers in the annals of aviation history.

At the turn of the 20th century, Longren, the son of Swedish immigrants, was a teenager getting by with little but natural mechanical aptitude. He built a motorcycle in 1904, the same year William Harley and Arthur Davidson road-tested their first. In 1905, Longren impressed the editor of the Leonardville Monitor when, at the age of 23, he drove his homebuilt car into town. “He made the car from practically nothing and it worked like a charm,” the paper reported. “Mr. Longren is quite a genius.”

During 1911, he quietly built his first airplane in Topeka, where he worked as a gasoline engine inspector for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway. Longren, his brother E.J., and friend William Janicke crafted the airplane from ash, bamboo, spruce-reinforced linen, and 2,500 feet of 1/16th-inch wire. While his design closely resembled the Curtiss he repaired, it was nine feet longer, 75 pounds heavier, and four feet wider in wingspan; its eight-cylinder, 60-horsepower Hall-Scott engine had more than twice the power of the Curtiss powerplant. The finished product was disassembled and trucked to a farm seven miles south of the city, where it was reassembled inside a tent to maintain secrecy.

Near sunset on September 2, 1911, with Longren in the pilot’s seat, the rear-facing prop was spun and the first airplane built and flown in Kansas shuddered forward. Its tricycle gear lifted gently, and the airplane flew a few hundred feet (exactly how many is in dispute), then touched down safely.

“The first time this plane was flown, I had never sat in any other airplane, or received any instructions from anyone experienced in flying,” Longren wrote years later in a scrapbook he sent to the Kansas State Historical Society. “The plane was also an unknown quantity because its balance and airworthiness was a big question. No one with any airplane building experience was consulted or rendered assistance.”

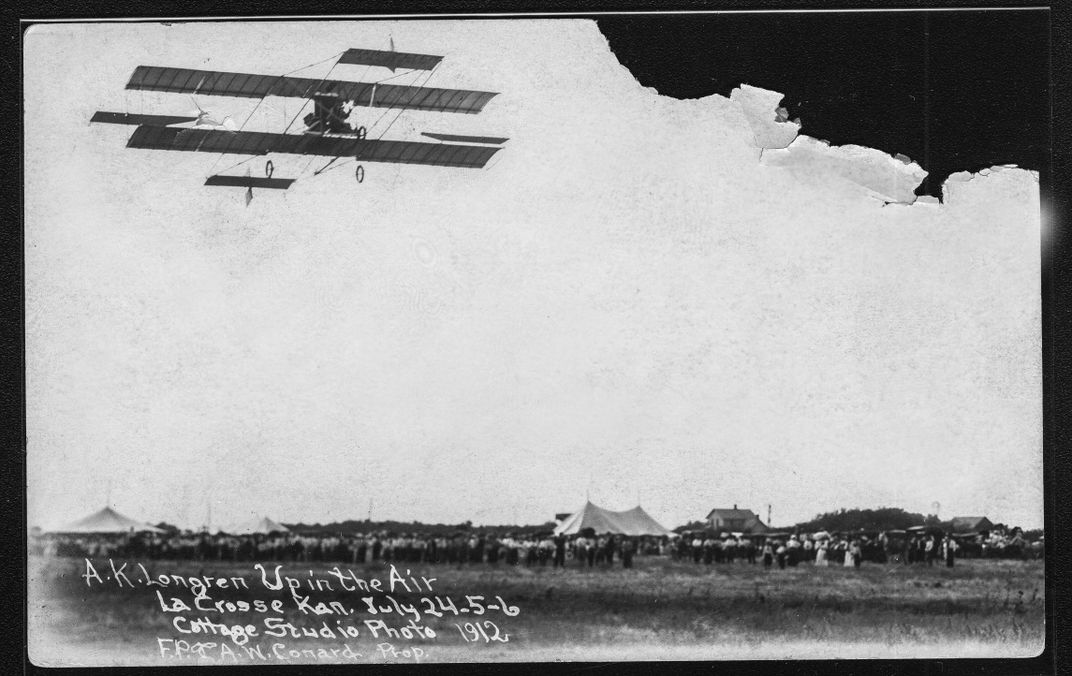

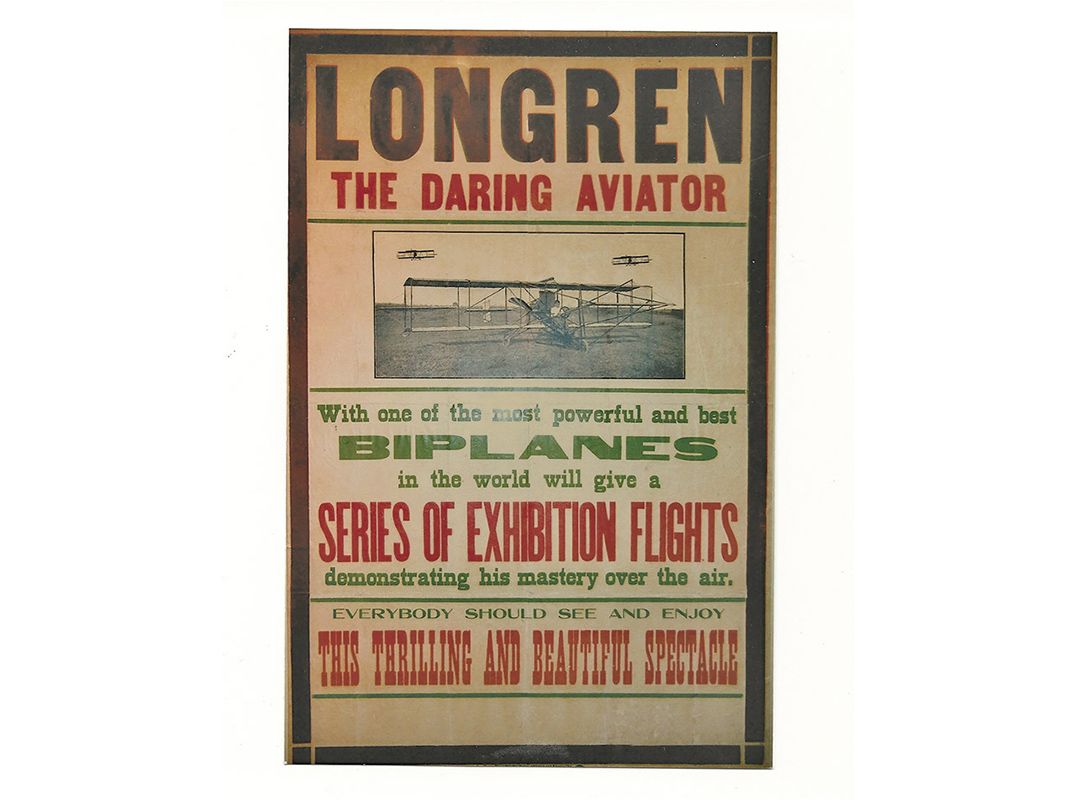

Longren went public a few days later. He first thrilled crowds at Topeka’s state fairgrounds before piloting the craft over the dome of the 325-foot-tall state capitol and scooted south, landing in a field before the three-gallon fuel tank ran dry. News of the flight quickly spread. County fair organizers and chambers of commerce begged Longren to visit their venues. Longren, ever cautious, declined. “He wishes to perfect himself in the handling of the machine a little more before accepting any offers” is what one associate told the Clay Center Dispatch-Republican, though by then Longren already had. In any case, his flight over Topeka was the first of 1,372 exhibitions; in all that time, the worst accident he suffered, while landing in a roughly plowed field, resulted only in a cracked strut.

A local financial backer sent Longren barnstorming across Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, each exhibition earning the airplane designer about $350. Awed crowds included a thousand Cheyenne Indians encamped near Watonga, Oklahoma. The income paid for a second airplane in 1912, a shorter, smaller version of the original.

The exhibitions and airplane-building continued, but the law of averages finally overtook Longren: In a crack-up in Abilene, Texas, in 1915, he broke a leg. An accident two years later was financially painful: While flying to LeRoy, Kansas, to meet desperately needed investors, his engine malfunctioned, and the airplane dropped from the sky and killed a cow. The cow cost Longren $100; the wreck cost him his investors.

So Longren’s first aviation company failed. But unlike many companies at the time, the quality of his product was not the problem. He designed, constructed, and sold 10 models, from open-frame pusher types to “tractor” airplanes with three-blade propellers. All responded nimbly to pilot controls, maintained their structural integrity in flight, and withstood the stresses of primitive landing surfaces. One surviving airplane, his fifth (built with parts of the first), today hangs in the Kansas Museum of History in Topeka. Each design roughly copied other manufacturers’ airplanes, but the pattern would not persist. Longren was an innovator, not a replicator.

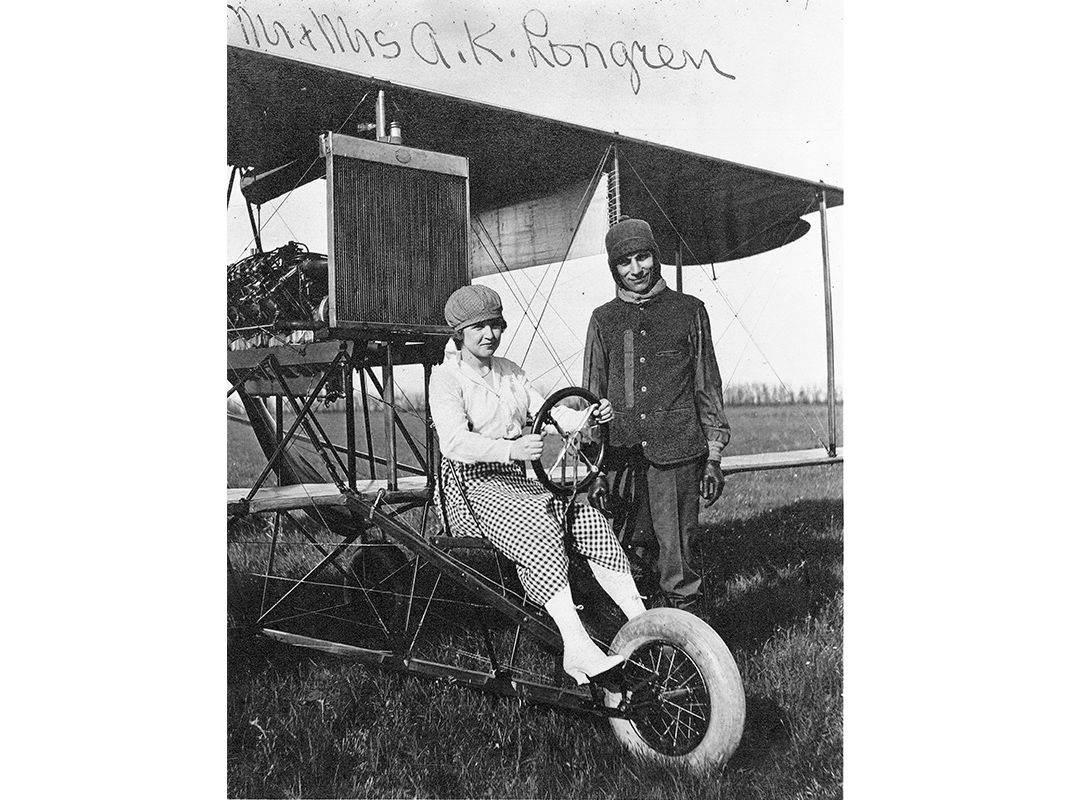

While barnstorming in Minneapolis, Kansas, Longren met Dolly Trent and married her after she began work as a nurse in Kansas City. She became a key partner in her husband’s business. Dolly sewed cloth wing covers, helped clean up castor oil spills in the factory assembly line, and dreamed up marketing slogans: “Watch it climb, see it fly, you’ll own a Longren by and by.” She was a bubbly counterpart to her taciturn husband.

Temporarily out of business, Longren found a job during World War I as chief inspector of aircraft at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio. For a year and a half, the self-taught airplane-maker mingled with test pilots and designers at America’s first military aviation research and development center, and at war’s end in 1919, he returned to Topeka primed to build another airplane.

This model would be for “the doctor, the ranchman, the traveling man and the farmer,” he declared, and those buyers could conveniently park the aircraft in their garages. The populist model was dubbed The New Longren Airplane, or sometimes the Longren AK.

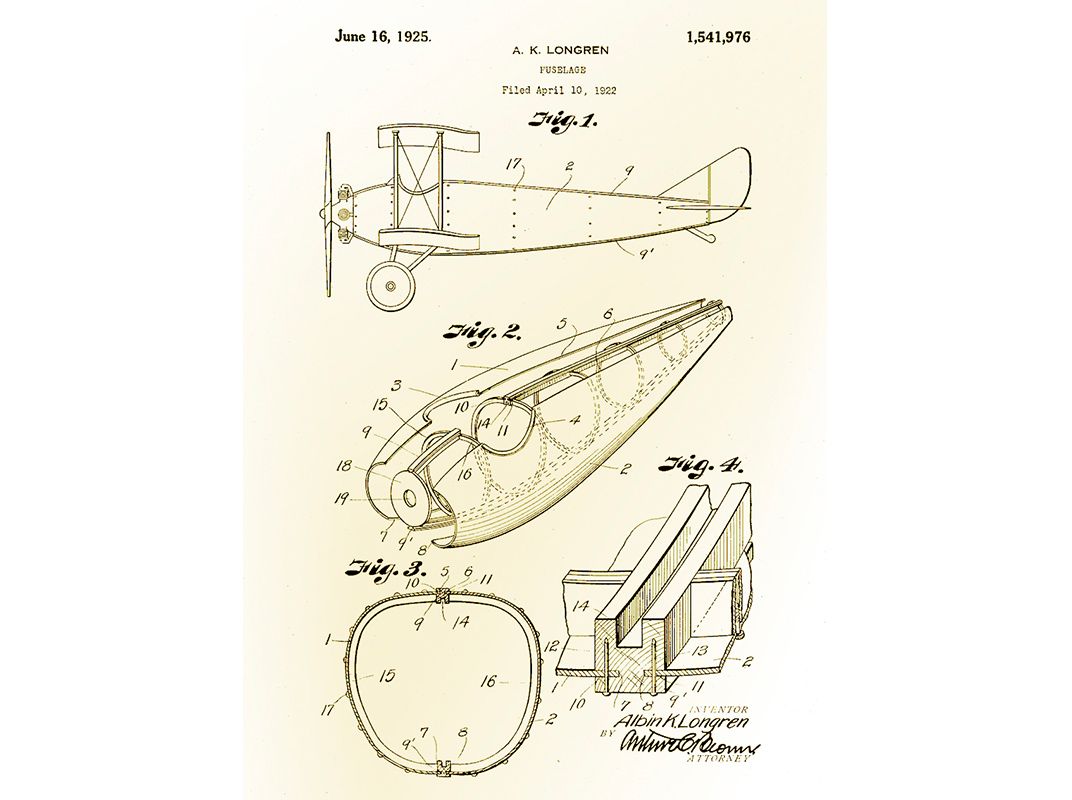

The two-seat biplane was just 19 feet long. Weighing 550 pounds, it was powered by a 60-hp Anzani three-cylinder radial engine and could take off and land in short distances. What really set it apart from the competition were folding wings and a fuselage containing vulcanized fiber. A pair of wheels was attached to the tailskid, and with wings tucked, the airplane could be towed backward into a garage. It was, Longren wrote in advertisements, “by far the best solution to the housing problem ever offered.” Dolly hit upon the marketing idea of showing the wings locked in flight position with the caption “Open for business.”

The fuselage consisted of a vulcanized fiber sheet incised in diamond patterns and sandwiched between two wood veneers. The three-ply bonded material was soaked in warm water, placed in dies, and formed under three tons of pressure into a half-cylindrical aerodynamic shape. The fuselage halves were affixed to ash longerons to form the world’s first semi-monocoque, truly composite shell fuselage. Other builders had shaped fuselages of plywood or veneer strips, but Longren introduced the (non-wood) fibrous sheet that enhanced the shell’s strength. Military reviewers later marveled that bullets didn’t shatter it.

The airplane could fly well too. Longren sent his Longren AK to an interstate airshow in Concordia, Kansas, where it finished second in a climbing contest, eclipsed only by one of his H-2 tractor models. At an American Legion meet in Kansas City, Missouri, the airplane set a record of 38 consecutive loops, which must have been exhausting. It finished second in a Special Class Efficiency Race in Omaha—a contest that calculated points on an airplane’s total performance—then won a 100-mile race in Salina, Kansas. On another occasion, a test pilot zipped up to 18,800 feet in it before thinning oxygen forced him to descend.

When a U.S. naval aircraft general inspector, Karl Smith, visited the Topeka factory, he was impressed to see that Longren’s fuselage was formed with such precision from dies made of relatively rough concrete, rather than cast iron. “However, with this more or less unsatisfactory equipment, The Longren Aircraft Corp. is able to produce a body which is phenomenal in its strength and particularly easy to build,” Smith said in his evaluation.

He recommended that the Navy purchase a New Longren immediately. “Personally I do not know the financial condition of the corporation, but if necessary, in view of the unusualness of this aircraft, I believe it would pay the Bureau to bear the cost of (cast-iron) dies and jigs.” The Navy quickly bought three airplanes for testing at McCook Field and Pensacola, Florida.

The tests went well. Lieutenant J.B. Kneip of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics gave the airplane a thumbs-up. “It’s easy to land; plane practically lands itself,” he wrote in his official assessment in February 1924, later telling the Topeka Journal: “They are as sweet a small craft as I ever piloted, and I think the Navy Department has finally found the airplane for which it wished.” Letters poured in from potential buyers all over, including Europe, China, and the Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, in 1926 the company went bankrupt. Despite the airplane’s reasonable $2,465 (about $30,000 today) price tag, surplus Curtiss Jennys from World War I were even cheaper. And people did not find the idea of an airplane in the garage as appealing as Longren had imagined. The hoped-for Navy purchase fell through as well; despite assurances from local banks and politicians, financial support was not forthcoming, and the Navy concluded it never would be. Naval officials were unconvinced the company could produce the aircraft in sufficient numbers to warrant a large purchase.

Smith called Longren’s production line techniques the best he’d ever seen, but he also saw the trouble Longren created for himself, noting in his evaluation that Longren’s insistence on perfection “is the one big bone of contention in the factory.” Paul Longren, a grand-nephew of the plane-maker, backs up Smith’s observation. “A.K. was a real stickler,” he tells me. “No smoking on the floor. No drinking. No chewing. And he was always stopping production after lying awake at night thinking about something.”

A plant manager with authority might have saved the day. Instead, perfectionism kept Longren from enjoying a profitable aviation career.

His exacting personality also may have affected his marriage. After years of toiling in factories together, the childless couple drifted apart amid the stress of the second business failure. There was no bitterness in the parting, family members say, but they never saw each other again. Dolly Longren succeeded as a New York City antiques dealer and outlived her husband by 20 years.

Jobless again, Longren spent most of 1927 vacationing alone in British Columbia, and if he did any planning for the next stage of his career, the years immediately following were not proof of it. He became an itinerant aviation executive, carrying his expertise from company to company, never staying long in one place.

First Longren went to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to become vice president of Mid-Continent Aircraft Company (later Spartan Aircraft Company). There his compelling need to tweak got him into trouble: He impulsively made a production-line change while the company president was away, and was fired when the president returned. In 1929, Longren drifted down to San Antonio, Texas, where a group of businessmen asked him to design and build an “Alamo” airplane. That project disappeared shortly in the dust of Wall Street’s crash.

By then, Longren had been in aviation long enough to begin to think about his legacy. So he returned to Topeka, checked into the Jayhawk Hotel, and assembled photos, recollections, and testimony of his airplane-making. He contributed the material to the Kansas Historical Society and applied for membership to the Early Birds of Aviation, an organization founded in 1928 to honor pre-1917 aviators. He was accepted, then he went back to work.

Rather than start yet another company, Longren became a consultant. His new stationery letterhead declared, “Better Airplanes…Faster Production Methods.” He was, after all, a mechanical engineer, not a holder of aeronautical degrees. He offered his clients expertise in aeronautics and manufacturing.

In 1930, Longren moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where he took up residence in a series of hotels, and contracted with Butler Manufacturing during the company’s brief foray into aviation. Its Blackhawk airplane was struggling to win Civil Aeronautic Authority certification; Longren modified the airplane and got it certified. Just 11 Blackhawks were built, however, before Butler abandoned the project and retreated to building grain bins.

Longren’s manufacturing ideas were adopted by Luscombe Aircraft, founded by Don Luscombe of Monocoupe fame. In the former Blackhawk factory, Luscombe’s Phantom took shape: the first mass-produced aircraft with an all-aluminum, semi-monocoque fuselage—a patented Longren idea.

His revolutionary “stretch-forming” manufacturing process turned aluminum panels into seamlessly interconnecting aeronautical forms, so airplane-makers could create complex fuselage panels in standardized mass quantities. Though the Phantom wasn’t a commercial success, its fuselage was the shape of things to come.

Longren once again felt an itch to build and attracted enough Kansas City investors—some of them a little shady, according to Longren family lore—to launch yet another iteration of Longren Aircraft in the again-idle Blackhawk factory. The result was a sleek, aluminum-sheathed biplane with a 120-hp Martin engine that Aviation Engineering magazine featured in February 1933.

But the company folded after building just three airplanes. Longren kept one and flew west to Wichita, where he had been invited to become vice president of Cessna Aircraft Company.

Kansas pioneer aviator Clyde Cessna (who began his flying in Oklahoma a few months before Longren did in Kansas) went bankrupt in 1932. Two years later, Clyde’s nephews Dwane and Dwight Wallace restarted the company, with Clyde as president. In 1935, Longren was offered the vice president’s spot plus $22,000 in Cessna stock in exchange for his half-dozen aviation patents.

It was an odd pairing. Longren brought to Cessna his valuable patents, manufacturing credentials, and airplane design successes. He served as the number-two executive, yet he apparently had no voice in decision-making, and company records make virtually no mention of him. “I’m a little embarrassed,” says Russ Meyer, a former Cessna chief executive. “I consider myself something of an historian, certainly of aviation, but I have never heard of Mr. Longren.” A 1937 cover letter from Dwight Wallace to Longren refers to an agreement conferring “manufacturing rights of all four, five and six-place fuselages.” Longren’s family members speculate that Longren helped with the development of the Cessna T-50, the twin-engine light transport plane that first flew in 1939.

Longren and Clyde Cessna, who became friends, were both eventually turned out to pasture by Dwane Wallace. The official Cessna story is that Clyde retired in 1936 to return to his farming, but his aviation partner and son, Eldon Cessna, disputed that in a 1987 Wichita Eagle article: “He was put out of Cessna Aircraft Co. He was forced out in a power play.” Longren told the same story, according to his grand-nephew, Paul Longren. “He said Clyde got the shaft and wasn’t happy about it at all,” he tells me. “A.K. thought it was pretty shabby treatment.”

Longren left Cessna and in 1938 flew his personal New Longren to California to start a business in Torrance—and this time Longren Aircraft had lasting success. It did not produce any airplanes. Rather, it employed Longren’s hydraulic stretch-forming process to produce bulkheads, fuselages, and other aeronautical parts for World War II-era airplane-makers. Longren’s West Coast clients included Santa Monica-based Douglas Aircraft, Burbank-based Lockheed, Seattle’s Boeing, and a young company called Northrop. Longren prospered before selling the firm in 1945, and the company flourished until at least 1960 before being absorbed into the larger Acme Aircraft Company.

Longren retired to a 3,000-acre northern California ranch, where he let lapse thousands of acres of leased grazing land and instead grew wheat and alfalfa, and had loggers drop Ponderosa pine trees. He bought a Ford tractor and an Allis-Chalmers round-baler (the engineering of which he constantly berated) and lived out his days in agrarian comfort.

Albin Longren never returned to Leonardville. He was a celebrity in his hometown but perhaps not beloved; many friends and neighbors had bought stock in his companies, and some bitterness developed upon bankruptcy. When Longren died in 1950, his body was brought to the cemetery outside Leonardville, a short biplane ride from his birthplace.

Contributor Giles Lambertson is a native Kansan.