Cancelled: Princess, Dethroned

A British aircraft company could not give up the ship.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Princess-Dethroned-9-1-2012-1_FLASH.jpg)

For flying boats, the 1930s were the glory years. Pan Am was sending its big Sikorskys and Martins, and ultimately the Boeing 314 Clippers, across the Pacific and down to South America. The British had linked their African, Middle Eastern, Indian, and Australasian holdings with a series of Empire Flying Boats operating from the Solent, a wide, sheltered strait off the south coast of England.

Although flying boats were expensive to maintain, since saltwater dines on aluminum, and they were slow and draggy, the boats were capacious: The bigger a hull, the better its seaworthiness and stability on the water. And there was no need for landing gear to support all that weight. If a flying boat ran into trouble, the theory went, it could land on a body of water, which makes up 70 percent of Earth’s surface.

But World War II would not be fought with flying boats. Bomber runways were built all over the globe, and military air transport’s legacy was the land-based airliner industry.

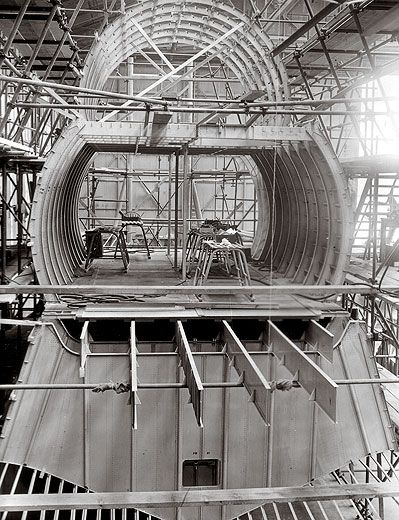

In 1945, British manufacturer Saunders-Roe, having built flying boats since 1912 (as Saunders, before being bought by Roe), floated a proposal for a gargantuan flying boat, the Princess, smaller than the Hughes Hercules but far bigger than the American colossus, the Martin Mars. The United Kingdom flag carrier, British Overseas Airways Corporation, which was flying the Short Empire, the civil version of the Short Sunderland patrol bomber, ordered three prototypes; BOAC planned to run postwar “wet routes” as well as landplane legs. The Empires were big enough that some who saw them taxiing majestically back and forth on the Solent assumed this was how they crossed oceans, but the Princess would carry 105 passengers―—an unprecedented load—―and cruise at 360 mph, a speed that was attainable thanks largely to a low-drag hull bottom and retractable wingtip floats.

By the time the Princess first flew, in 1952, its Bristol Proteus turboprop engines had already been de-rated from 3,780 shaft-horsepower to 2,850. Ten were crammed inside the Princess’ vast wings, the two outermost each driving a single propeller; the inboard eight were mounted in pairs to drive four sets of contra-rotating props. The complex gearboxes through which the “Twinned Proteus” drove those props were a chronic problem, and the powerplants were complex enough to warrant two flight engineers.

Only one Princess ever flew, for just under 98 hours of testing. The other two were completed but quickly mothballed, since BOAC had already abandoned flying boats nearly two years earlier. Saunders-Roe promoted the SR.45 as a long-range troop carrier, but the Brits had no need, since they were giving up their east-of-Suez empire. NASA briefly thought of buying a Princess to carry Saturn V rockets from Huntsville, Alabama, to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and the U.S. Navy entertained the idea of having Convair re-power the boats with experimental nuclear reactors. Neither notion panned out. The three Princesses, their airframes having corroded while in storage, were scrapped by 1967.

Some remember the Princess from its flybys at England’s Farnborough airshow, where its slow-turning, contra-rotating props created the airplane’s characteristic muttering, low-pitch growl. “From the direction of the Solent the great Princess flying boat appeared,” wrote James Hamilton-Patterson in Empire of the Clouds: When Britain’s Aircraft Ruled the World. “Saunders-Roe’s chief pilot, Geoffrey Tyson…[brought it] past the stands at Farnborough in an almost vertical bank, one wingtip perilously close to the grass. Years later, it was revealed that he was traveling so fast that a glitch in the powered control system had almost prevented him from rolling back upright. It had cost him sustained physical effort to haul the massive machine back onto an even keel, having been for a long moment only feet away from…disaster.”

Saunders-Roe then designed the Duchess, a six-jet, swept-wing version of the Princess, and in 1956 proposed a 1,000-passenger flying boat with 24 jet engines. Neither had any takers.

Stephan Wilkinson’s new book Skygirls: A Photographic History of the Airline Stewardess, co-authored with his college classmate and fellow pilot Bruce McAllister, has just been released.