Coanda’s Claim

The story of a jet flight in 1910, just seven years after Kitty Hawk, may be too good to be true.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/coanda-flash.jpg)

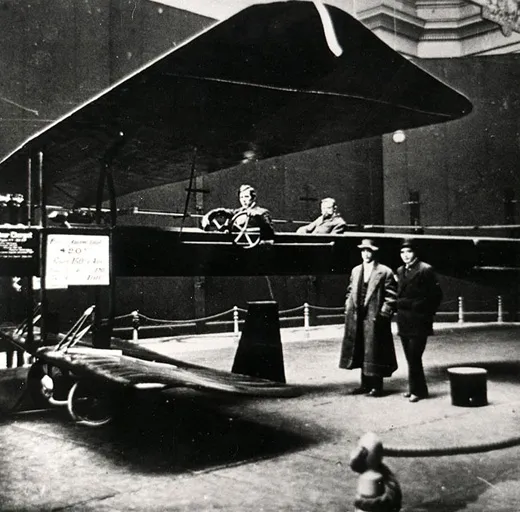

The weird-looking flying machine was called “Turbo-Propulseur” by its inventor, the brilliant Romanian aeronautical engineer Henri Coanda. A hundred years ago this week, on December 10, 1910, the Propulseur accidentally flew—or so Coanda would later claim—during taxiing tests at Issy-les-Moulineaux, outside Paris. If true, it was the world’s first jet flight. But Coanda’s accounts of the alleged flight changed markedly over the years, and a close examination of his stories, as well as his patent documents, leave more than a little doubt that it happened at all.

The Propulseur caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the Second International Exposition of Aerial Locomotion, held at the Grand Palais in Paris from October 15 to November 2, 1910. Coanda’s invention was strikingly different from the usual flimsy biplanes of the day. Instead of a propeller, the revolutionary monoplane had an inverted flower pot-shaped front, with built-in rotary blades arranged in a swirl pattern. The heart of the machine was an internal turbine screw driven by a conventional four-cylinder, 50-horespower Clerget engine. The Clerget was to turn the rotary blades, thus sucking in air through the turbine while “the heat of the exhausting gases…exited...at the rear, driving the plane forward by reaction propulsion,” according to a December 1, 1910, article in the journal La Technique Aeronautique.

Coanda’s patent (French patent No. 416,54, dated October 22, 1910) gives more insight into how the engine actually worked. When air rushed in the front, it passed though different channels that contracted and expanded it. In this way, the air’s “kinetic energy [was] converted into potential energy,” according to the patent. Next, the air was “directed to the diffuser...which then discharges it.”

To improve the efficiency of his machine, Coanda suggested that the channels be heated to increase the pressure of the air passing through them. Any heating agent would work, including exhaust gases from the engine. Moreover, this propulsion system could be applied to any vehicle, said Coanda—including a ship, “motor car,” or airplane.

What is notably lacking in the patent (including identical ones taken out in England and the United States) is any mention of injecting fuel, which in a true jet engine would combust with the incoming air. Judging only by the Turbo-Propulseur’s patent, it was no more than a large ducted fan, a super vacuum cleaner with wings. And it couldn’t have flown.

Throughout the Exposition, Coanda’s airplane was well publicized. Yet none of the reports hinted that the Propulseur on display was capable of actual flight. For instance, L’Aérophile observed: “If the machine would ever materialize as the inventor hoped, it would be a ‘beautiful dream.’ ”

And the accidental flight? At a speech before the Wings Club in New York in January 1956, when Coanda was 69 years old, he said of the Propulseur: “I intended to inject fuel into the air stream, which would be ignited by the exhaust gases....Thus I hoped to obtain the jet reaction desired...” That would appear to close the case: The inventor never finished his invention.

Why then, did he make a contradictory statement in an article published just a few months later in the Royal Air Force Flying Review, titled “It Actually Flew in 1910!” In the September 1956 issue, Coanda is quoted (by writer Rene Aubrey) saying that he did inject fuel. While taxiing and “concentrating on regulating the flow of petrol [gasoline] in the jet engine,” he said, “I suddenly saw the fortifications around the airfield looming up in front of me. There was only one thing to do. I lifted the machine off the ground.” Aubrey then writes that Coanda lost control of the plane and, “Injecting more fuel into the turbine, he suddenly found himself surrounded by flames. Desperately he cut off the fuel. The aircraft stalled and Coanda was thrown clear of the machine as it gently collapsed to the ground and burst into an inferno of fire. Coanda escaped with a few bruises....It was the end of his first jet flight.”

Another article on Coanda, in the March 1967 issue of Flying magazine, gives a precise date for this supposed flight: December 10, 1910. Could the date have been chosen to add authenticity to an unsubstantiated claim? A page-by-page search through the Paris newspaper Le Figaro for the entire month of December 1910 turns up no story about a flight or accident at Issy. Nor is there any mention in leading aviation journals of the day. Nothing. The only reference even closely related, in Flight, reports (under “Doings at Issy”) that in mid-December 1910 there was no flying due to bad weather.

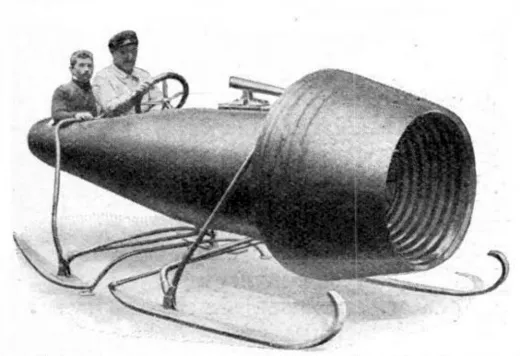

So the claim of a jet flight in 1910 doesn’t hold up to scrutiny, or at the very least needs corroboration. But Coanda’s story doesn’t end there. After the Propulseur was displayed in Paris, he was approached by Grand Duke Cyril, first cousin of Tsar Nicholas II, to make a sled for the Russian royal family. After all, the engine could propel an “aeroplane, ship, motor car, etc.” Coanda built it immediately, with the help of a French boat manufacturer. Instead of a Clerget, he fitted it with a six-cylinder 30-HP Grégoire engine.

The sled had the same inverted flower-pot front, but the body was teardrop-shaped, with two recessed passenger seats at the rear and large snow runners underneath. The sled was exhibited at the Twelfth Automobile Salon of France, also at the Grand Palais, from December 3 to 18, 1910, and was written up in leading car magazines. It was about 13.5 ft long, and was steered with an automobile steering wheel. The accounts say the sled was baptized for Cyril by Russian Orthodox priests using an improvised altar, in a shed usually occupied by motor boats and workmen.

But like the airplane, the sled appears to have been propelled by air alone—not hot exhaust gases produced by combustion, as in a true jet. Motor World called it “more of a ‘wind waggon’ than a tractive vehicle.” No wonder a drawing of it shows two people sitting directly on top of what would have been the turbine’s exhaust exit! Indeed, the passengers would have been cooked instantly if the Propulseur was a real jet.

After spending time and money on his Turbo Propulseur, Coanda may well have discovered that the vehicle’s thrust was embarrassingly feeble for an airplane, and better suited to pushing a sled over ice. Even then, it’s not clear that Cyril’s sled ever worked. The Motor (London) said the inventor claimed it “will be capable of 60 mph.” But no record has been found of an actual run. The Motor only concluded that the sled was to be sent to Russia.

As for Coanda, he was no doubt a skilled aeronautical designer, and became a Romanian national hero (the airport in Bucharest is named after him). But it appears his Turbo-Propulseur may not have quite worked out the way he envisioned. We may never know for sure.

Frank H. Winter is a freelance writer. He was on the staff of the National Air and Space Museum from 1970 to 2007, serving as the Curator of Rocketry.