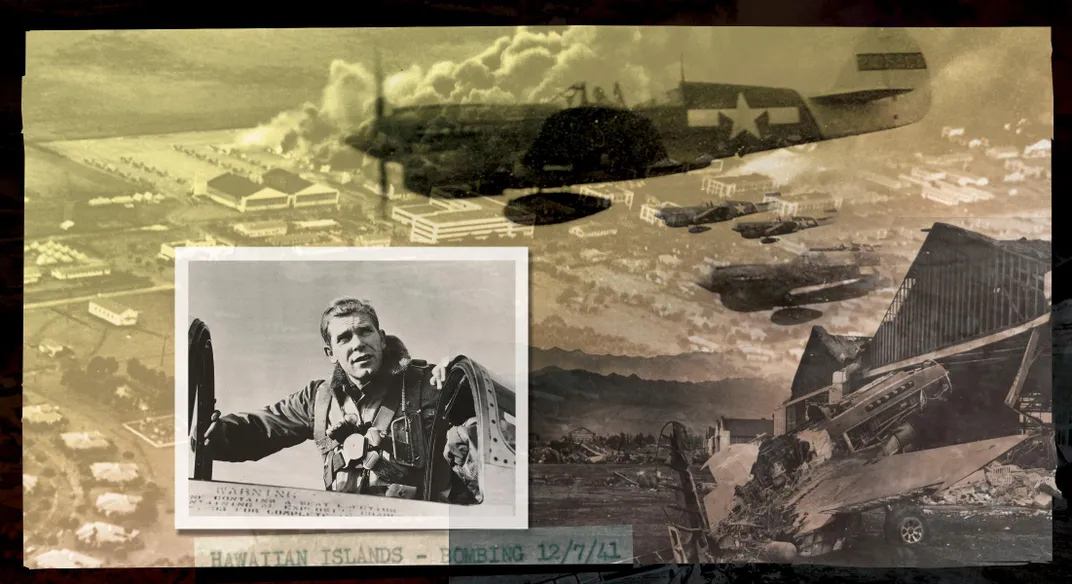

A Fighter Pilot at Pearl Harbor

Emmett “Cyclone” Davis remembers that horrifying day.

:focal(1651x667:1652x668)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/2c/3a2c2b0b-4e47-4de2-8533-8ab1a46bb476/08e_dj2015_davisviasaltlaketribunecyclone025ss_live.jpg)

United States Army Air Forces fighter pilot Emmett S. “Cyclone” Davis flew one of the first missions of World War II, and one of the last.

By the time Davis retired from the Air Force, in 1963, he had commanded five squadrons, six groups or wings, and an air division. He flew over 100 types of aircraft, from biplanes to Mach 2 jets.

After retirement from the Air Force, Davis worked for Hughes Aircraft, where he participated in the development of the Angle Rate Bombing System, helped evaluate performance of the Air Intercept Missile on the F-4, and helped arrange placement of the Hughes radar system in the F-15.

In a conversation with Rich Tuttle last May, Davis recalled his World War II exploits, and Davis’ son, J. Tucker Davis, elaborated on some of his father’s comments. Tucker Davis is writing a book about his father’s experiences. Emmett Davis died on November 3, 2015, as the magazine was going to press. He was 96 years old.

Tuttle: You were at Wheeler Field in Hawaii when the Japanese struck. What happened next?

Emmett Davis: There was a dance at the officers’ club Saturday night, and a poker game after the dance. I got to bed at three o’clock in the morning. That morning a friend awakened me and said, “The Japs are here!” I looked out the window and saw a Japanese dive bomber going down the flightline, so I jumped out of bed, put on my flightsuit, and ran down the hall. A friend saw me and said, “Come on, Cyclone!” We jumped in his convertible and drove to the flightline.

We got strafed by a Japanese [airplane] while we were driving down there, but they didn’t hit us. We parked and ran to the hangars and got strafed again but didn’t get hit. We had all the airplanes lined up wingtip to wingtip, and they were surrounded by fire, so I started bringing the airplanes out. I got three of them out. The fourth P-40 I decided to keep, but it didn’t have guns so I taxied to a redoubt. I got a sergeant and he and I broke through the door of the ammunition depot with a fire axe and got six machine guns.

We got the guns loaded. They made another strafing run at us but [missed]. They were so low I could see a Japanese rear-seat gunner grinning at us. I charged my guns and taxied out and took off. I called the controller and he sent me to Barber’s Point, where they thought an invasion was taking place. There was no invasion.

I intercepted three other P-40s from Wheeler Field, one flown by Gabreski [Lieutenant Francis Gabreski, the leading American ace in Europe]. They told us to escort some B-18s from Hickam Field to look for the Japanese fleet, but Navy guns were shooting at everything in the sky, so I told the flight controller at Fort Shafter to get the Navy under control or there would be no escort. We landed and refueled. We had two more patrols but they were uneventful.

Tell me about the big dogfight over Cape Gloucester, New Britain, on December 26, 1943, when the U.S. Marines invaded.

I flew two missions that day [in a P-40N from Finschafen, New Guinea]. I flew an early morning mission and I tested my guns, and my armament chief could see the guns had been fired, so when I came back and landed, he took the film out, but then he forgot to reload the camera. So anyway, I got in a fight and there was some question about how many airplanes I shot down, but I suspect I shot down at least seven.

But you got credit for two, right?

I got credit for two. My wingman saw the first two and so I got credit for that.

You shot down one other airplane, on September 27, 1943, giving you a total of three victories in World War II. [Richard] Dick Bong, the American ace with 40 victories, was under your command?

Bong was in a different unit, but he was allowed [by Fifth Air Force Fighter Command Headquarters] to shift around to get hot missions and fly with other people. When he broke Eddie Rickenbacker’s World War I record, he was flying with our unit [80th Fighter Squadron, Eighth Fighter Group].

Having flown one of the first missions of the war, at Pearl Harbor, your father also flew one of the last.

Tucker Davis: The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945; the second on Nagasaki on August 9. There was no indication at that point that Japan would surrender. So, on August 9, General Frederic Smith, commander of the Fifth Fighter Command, told my dad that the planned invasion [of the island of Kyushu] would proceed. The best intelligence available determined it was probably going to be better to attack from the north because air defenses there were assumed to be lighter.

Sixty-two P-38s, with Dad leading, took off from the island of Ie Shima, near Okinawa, on the morning of August 10. As they neared the target—probably flying through residual fallout of the Nagasaki atomic bomb the day before—Dad started to have a bad feeling about attacking from the north, so he swung the whole formation around to attack from the south. And as they did, the sky, at their exact altitude, and where they would have been, just went black with ack-ack.

One pilot, Arthur Lasker, said if it hadn’t been for Dad’s intuition, over half of the P-38s would have been lost. One guy had one of his engines shot out but he made it back. There were a couple of guys that had bullet holes, but they all made it home safely.

Dad’s story has always been that the two big bombs got the attention of the Japanese—but his 62 P-38s brought them to the table!