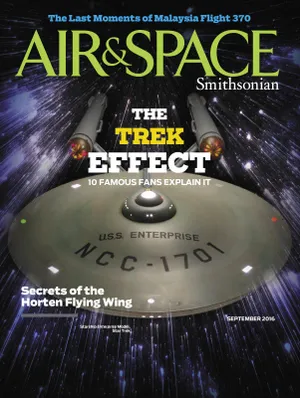

Restoring Germany’s Captured “Bat Wing”

A team of conservators works to preserve the innovative Horten Ho 229 V3.

:focal(640x349:641x350)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/50/ec50ab1f-d225-41cf-957b-d5bd63b9b2f5/16h_sep2016_eric_2000-9339_live.jpg)

The aircraft has always intrigued aviation fans. But after a 2009 National Geographic Channel special aired, touting the Horten Ho 229 V3 flying wing’s “stealthy” characteristics and claiming it was stored in “a secret government warehouse,” Internet forums went wild.

The “secret” warehouse was simply the National Air and Space Museum’s storage facility in Suitland, Maryland. The U.S. Army Air Forces had captured the flying wing prototype—along with hundreds of other German aircraft—near the end of World War II. In April 1945, George Patton’s Third Army found four steel-and-wood Horten prototypes; of three airframes, the V3 was nearest to completion, and was shipped to the United States. It made its way to the Smithsonian around 1952.

At the time, the Institution had a lot of airplanes but little display space. So the Horten remained in storage for almost 61 years, some of that time outdoors. In 2013, Museum staff began evaluating the Horten’s center section to see if it could be safely moved to the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center for conservation.

The aircraft features a steel-tube framework enclosed by a plywood skin, which had been damaged during storage: “The plywood was badly delaminating in some areas,” says Lauren Horelick, an objects conservator at the Museum.

While the initial objective was to stabilize the aircraft so that it could make the 40-mile trek from the Museum’s warehouse to its Virginia restoration facility, conservation staff gathered a wealth of information.

The center section’s structural wooden supports, the team discovered, are made from Scots pine—not a wood widely used for aircraft. It may have been chosen because of wartime shortages, but, says aeronautics curator Russell Lee, “we have to remember that this particular airframe was highly experimental. It was in no way designed to be a production airplane. If they had got it into production, they may well have used something very different.”

Conservators found two kinds of paint on the aircraft: The first is a blue-gray paint that was added by the U.S. Army Air Forces when the aircraft was displayed right after capture. But its original green paint appears on the interior and parts of the exterior plywood panels. The team considers the green paint unusual and has determined that its chemical composition is similar to that of fireproof paint developed in Germany during the war.

“We did a lot of analysis of the paint,” says Horelick, “and it was fascinating to see how advanced the Germans were, considering the limitations of plywood, and coming up with ways to enhance [that material’s] performance.”

So was it stealthy? The designer, Reimar Horten, claimed in 1983 that the flying wing was meant to include a kind of stealth capability that would make it difficult to detect with radar. In his 2011 book about the aircraft, Only the Wing, Lee recounts: “Reimar wrote that he planned to sandwich a mixture of sawdust, charcoal, and glue between the layers of wood that formed large areas of the exterior surface of the H IX jet wing to shield…the whole airplane from radar, because the charcoal should absorb the electrical waves.”

As the conservation team prepared the center section for its move, they examined the plywood skin for evidence of radar-absorbing compounds. If charcoal had been added to the flying wing in an effort to deflect radar, they would have expected to see a layer of it, something the team didn’t find.

The team did discover that two different adhesives were used to assemble the plywood panels, but only one of the adhesives—urea formaldehyde—can accept any sort of fillers or additives. Samples taken from the aircraft and analyzed under a digital microscope showed small black particles. The results of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy suggest the particles are bits of oxidized wood.

“We were finding that as we brushed our adhesive across our plywood repair material, we found small bits of this wood at the bottom of the adhesive jar,” says Horelick. “Based on this, I have a really strong suspicion that the little particles that we see in the Horten’s adhesive layer could be from the plywood manufacturing process.”

In 2008, engineers from Northrop Grumman, builder of the B-2 Spirit flying wing bomber, spent a day at the Museum looking at the Horten and making a number of radar measurements. “They published a scientific paper,” says Lee, “and the bottom line is that they couldn’t say the aircraft was any stealthier than a regular sheet of plywood.”

The public’s focus on the aircraft’s possible stealth aspects slightly dismays Horelick. “I think once we stop paying attention to the big picture, we lose perspective on the overall iconography of the piece, which was a leader in the streamlined, all-wing design. I feel that the emphasis should be less on these teeny particles and more on the overall swept-wing look of the aircraft.”

At some point in the aircraft’s history, engineers may have tested its Junkers Jumo 004 B-2 turbojet engines. The restoration team found scorch marks on the belly panels that line up with the engine exhaust tubes. “It is, in fact, wood scorching,” says Horelick. “It can’t be mistaken for anything else.”

“It’s on both sides, under both engines,” says Lee. “I found one document that after the Horten jet got to Wright Field, [the Army Air Forces] had been working on the jet with the goal of flying it. Very quickly they decided to abandon that effort. Why, is not clear.

“That’s why the Museum preserves these artifacts rather than sandblasting all the finish off,” says Lee. “There’s always these incredible things to find out.”

The center section of the Horten Ho 229 V3 is currently on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center’s restoration hangar. Its wings sit close by. The next steps in its restoration and preservation include treating the plywood wings and rotating the big, heavy outer wing panels from a vertical to a horizontal orientation. When that happens, the stark beauty of the world’s first jet-powered flying wing will be seen once again.