The plane that taught Anne Morrow Lindbergh to fly is flying again.

Lindbergh’s Trainer: The Brunner-Winkle Bird

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bird631x300.jpg)

The same airplane, a rare Brunner-Winkle Bird BK biplane, is the subject of two photographic portraits, shot 82 years apart. In each, a smiling woman named Anne looks over her shoulder from the rear cockpit at her husband, standing on the ground just behind her. The first photo is of Anne Morrow Lindbergh and her husband Charles, taken in May 1931 on New York’s Long Island. The second is of Anne Fichera and her husband Joe, taken in January 2013 at their home at the Kentmorr Airpark in Stevensville, Maryland.

Joe had all but finished restoring the Lindberghs’ Bird to its original condition. Of the many aircraft Fichera had worked on, the Bird was his first, longest, and best-loved project. And it was his last. Last January 23, less than two weeks after the photo was taken, Fichera died at 92, and the Bird that was not only his love is now his legacy.

Charles Lindbergh bought the Bird in September 1930 for his wife to complete her pilot training, and registered it in her name. The aircraft was built by the Brunner-Winkle company of Glendale, New York, which between 1928 and 1931 turned out 220. Known for its durability and ease of handling, the Bird was especially popular with female pilots, according to the Virginia Aviation Museum, which exhibits one at its facility in Richmond. Only 70 remain.

Anne practiced for her pilot license in the Bird in May 1931 at the Long Island Aviation Country Club. Afterward, she recalled in her book, Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead, she went “round and round the field alone in that plane, making one hideously bumpy landing after another.”

Charles, her instructor, insisted she keep going until she made a decent landing. Soon, she wrote, she experienced “absolute exultation” as she made her first solo flight away from the airport, flying over New York City, and landing at Teterboro airport in New Jersey. Her recollection: “[M]y dream as a young girl [had] at last come true.” She passed her Department of Commerce flight tests on May 29, 1931.

In 1946, after changing hands 10 times, the Bird landed in storage at the Lawrence Airport in North Andover, Massachusetts. A young Joe Fichera bought it for $600, spending everything he had—$300—and borrowing the rest. He knew of its Lindbergh history, but at the time, he did not give it much thought. He had just gotten out of the military, was anxious to fly, and wanted an airplane. The Bird was available and ready to fly. But the wind had other ideas.

On May 9, 1946, before Fichera had a chance to fly the Bird, a strong gust ripped its steel moorings from the ground and lifted the aircraft into the air (along with six men struggling to hold it down). The men let go; the Bird shot up and flipped over, crashing down on its upper wing.

Fichera was unable to repair the airplane then; he was recalled to active duty at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. There, he established a program for training airframe-and-engine mechanics, and volunteered the Bird as his students’ project. By 1950, Fichera was flying the aircraft again, but not for long. One day in April, the engine quit on takeoff at Hyde Field in Clinton, Maryland. A few moments later, the Bird was once again on its back (though Fichera was unhurt).

This time the airplane would wait 61 years to be restored. Fichera moved on to other things, including a job at the National Air and Space Museum’s restoration shop, the Paul E. Garber facility in Suitland, Maryland, where he restored some airplanes and compiled evaluation reports on others. He retired in 1984, but it wasn’t until 2001 that Fichera, at age 80, began the final restoration. He was remarkably matter-of-fact about the effort. “It mostly just needed new wings,” he told me. “The rest of it was just cleaning it up, new floorboards, stuff like that.”

But it took him 12 painstaking years, working almost every day. The only major component that needed replacing was the top wing. Fichera worked from original plans, and from the wing’s intact right half. Most of the other original parts could be salvaged—even Anne Lindbergh’s dusty seat cushion.

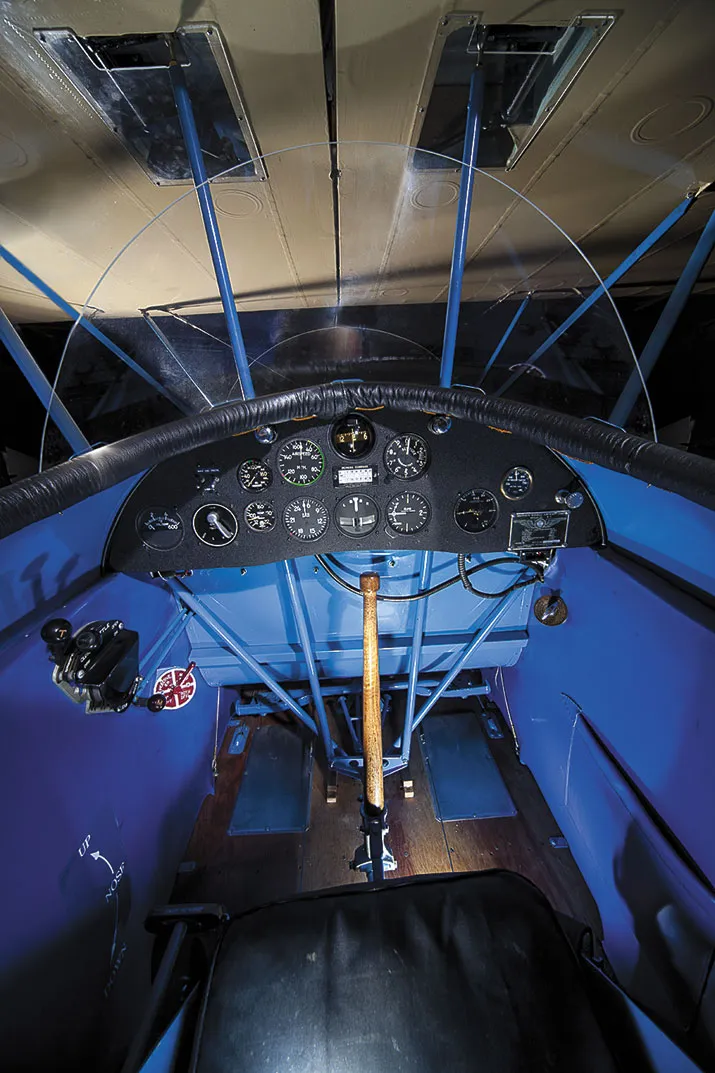

The five-cylinder, 100-horsepower Kinner engine was completely overhauled, but needed only new rings, valve guides, and “stuff that wears out,” Fichera said. The bent propeller was straightened out and polished. Only one instrument—the front cockpit airspeed indicator—was replaced. In his sole concession to modern materials, Fichera coated the airplane with a polyester finish called Ceconite to protect it from the elements.

Fichera replicated a brilliant Bahama blue he found on the landing gear—the color it was during the Lindbergh era—and determined that cream had been the color of the stripe and the wings.

The Bird has other Lindbergh traces: an extra storage compartment in front of the two-place front cockpit, and dial fuel gauges in both cockpits. Fichera had reproductions made of the lights that Lindbergh had installed on the wingtips and rudder. But the most personal touch is out of view. Before selling it back to the manufacturer, Lindbergh autographed the Bird on a piece of plywood inside the right lower wing walkway.

Like Lindbergh, Fichera taught with the Bird. Although several of his friends and colleagues toiled on the restoration, he welcomed newcomers, including two midshipmen from the nearby Naval Academy, who helped with some of the heavy lifting, and a 10-year-old named Gretta Thorwarth, who had a keen interest in airplanes. Her father, who worked on the Bird, brought her along to learn how to rib stitch. Gretta’s careful work, small size, and youthful, boundless enthusiasm enabled her to work inside and all over the Bird.

“I got to do so many crazy, cool things with him,” she says of working with Fichera. “Compression-checking a pile of valve springs, sorting through cylinders when he was picking out the best ones for overhaul, doping [by brush] the landing gear fairings, hooking up lines, instruments, safetying hardware, helping to fit new metal fairings, taping out numbers and letters for painting, painting in the red ‘Kinner’ letters on the fresh rocker covers.”

Now 17, she can’t imagine her life without the influence of Fichera, “an 80-, 90-some-year-old fountain of endless information from generations past,” she says. “You can’t find people like this anymore.”

Fichera’s vision for the project—to have the airplane flying regularly—is almost complete. The Bird received its airworthiness certificate from the Federal Aviation Administration in 2012, and flew again last July, with family friend Bob Newhouse at the controls. Now Anne plans to have Newhouse take the Bird to fly-ins for antique aircraft at Horn Point, Maryland, on May 18 and Blakesburg, Iowa, in August.

Paul Glenshaw, director of the Discovery of Flight Foundation, last wrote “Kings of the Air” (Feb./Mar. 2013).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lindbergh-2-715.jpg)