Moments and Milestones: Once Around

The 75th anniversary of a round-the-world trip.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Moments_and_Milestones_0911_1_FLASH.jpg)

This October marks the 75th anniversary of a globe-circling race not unlike the ones on today’s reality TV shows. In 1936, three New York journalists set out to travel around the world using “established means” of transportation available to anyone who could afford the ticket. The point of the contest was to demonstrate that air travel was accessible to all and was rapidly shrinking the world—and to pump up newsstand sales. Leo Kieran was a reporter for the New York Times, and Herbert R. Ekins wrote for the World-Telegram. At the last minute, they were joined by Dorothy Kilgallen of the Evening Journal, a 23-year-old novice crime reporter with a couple of semesters of college and a pedigree: She was the daughter of James Kilgallen, a veteran Hearst writer. The National Aeronautic Association handled the timing of the race, and the clocks started when the participants left their papers’ offices on the evening of September 30.

The first leg was a dash to Lakehurst, New Jersey, in a driving rainstorm that put all three on highways instead of in aircraft. They were headed to the Hindenburg. Kilgallen almost missed the dirigible, but the crew held the departure until she boarded. All three journalists cabled their accounts of each day to their newsrooms. (Read excerpts from Kilgallen's dispatches.) As it turned out, Kilgallen and Kieran were to be companions through much of the adventure. After the Hindenburg arrived late in Frankfurt, Germany, Ekins, aviation-savvy and clearly set on winning, jumped on a KLM DC-2, an airliner that two years earlier had come in second in a race from London to Melbourne.

For Kilgallen and Kieran, it was planes, trains, and automobiles as they battled delays on their journey to Brindisi, on the heel of Italy. Kieran abandoned a slow train and hired a driver, who drove him down through Italy at breakneck speed. He and Kilgallen had cast their lot with the British flag carrier, Imperial Airways; they planned to take an airliner from Brindisi to Hong Kong. Imperial was to prove safe, cautious—and slow. They lost seven hours when their departure for Athens was delayed by winds, which was just as well for Kilgallen, who had arrived in Brindisi late because a locomotive had broken down. During the trip to Hong Kong, Kilgallen noted repeatedly that the airline’s schedule seemed to be based on mealtimes.

Kilgallen was content to soak up the sights, sounds, and smells of the exotic lands in which she alighted. All of it seemed out of a storybook, she wrote, as she overflew jungles teeming with lions and leopards, and waters that were “shark infested.” She never got to meet Chancellor Hitler, she sighed, but there were lots of grand poobahs the rest of the way. She parted ways with Kieran at Bangkok, Siam, and for some unfathomable reason took a single-engine de Havilland Puss Moth, whose pilot got lost in Indochina and made a scary landing in a field before finding his way to Hong Kong.

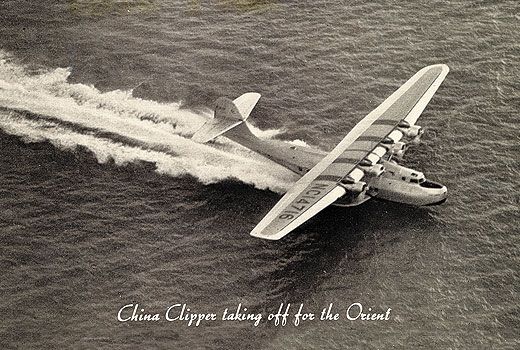

By the time both reporters arrived in Hong Kong to board a steamship for Manila and their homebound leg aboard Pan American’s China Clipper, they learned that Ekins was long gone aboard an earlier no-passenger Pan Am trial flight. He’d talked his way aboard as “crew,” which violated the rules, as Kieran reminded Times readers.

Even so, Ekins, having made his trip in 18 days, was declared the winner, a victory that Kieran acknowledged sourly in print, as he and Kilgallen sat in Manila until a typhoon blew through. They finally made Honolulu on October 22, and Kieran was in New York three days later, with an elapsed time of 24 days, 14-plus hours. Kilgallen, apparently through the offices of her father, had arranged for a flight from San Francisco to New York (via Newark) in a speedy Vultee. She set some records, including “the first woman” kind and also an absolute record for 5,000 miles in the air on her Honolulu-to-Newark leg. Her total time was 24 days, 12 hours, but the race had turned her into such a celebrity that in many ways, she was the winner.