A World War I Aircraft Enthusiast’s Collection Tracks the Evolution of the Species

Javier Arango goes on a mission to find authenticity by reconstructing airplanes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/a2/b0a21a9e-0f97-417d-9c13-8531b708fa14/04e_dj13_spadxiiiarango1561_live.jpg)

It’s a windless morning near the California town of Paso Robles, all birdsong and stillness—until an airplane shatters the calm with the startling brrruuuppp…brruuppp of its rotary engine. A Sopwith Camel crosses the fence and seems to pause, kestrel-like, before alighting on the grass. Rocking on the uneven ground, it taxis to the hangar, where, as soon as the propeller stops, a crewman places an oil tray beneath its nose and begins to wipe down its dripping cowl. The pilot extricates himself from the tiny cockpit and hops to the ground.

Javier Arango speaks softly, with a faint accent of his native Spanish. Now 50, he was in high school when his father bought the first of what would become one of the world’s finest private collections of World War I aircraft.

“I’ve been interested in airplanes all my life,” says Arango, owner of the Aeroplane Collection and a Board member of the National Air and Space Museum. “Especially antique airplanes, for some strange reason. My original fascination was with the personalities of the first world war, and I read about the aces and what they did and how they flew. In the late 1970s my father and I met some people from Flabob airport, Jim Appleby and Mac McRiley, who built replicas of those old airplanes, and my father had McRiley build a Fokker Triplane for us. That airplane flew in 1981. But we had no idea it was going to turn into a ‘collection’!” That replica of the Fokker Dr.1 triplane of Manfred von Richthofen was less a historical artifact than a functional toy.

Externally, it resembled the original, but it had a modern engine, propeller, and brakes, a tailwheel rather than a skid, and a radio, so it could be operated among modern airplanes at conventional airports.

His interest piqued by the Fokker, Arango’s father next acquired a Sopwith Strutter replica built by Jim and Zona Appleby. The Strutter—so called because of the arrangement of one and a half struts supporting the upper wing—was a two-seater, much larger than the Fokker. It too had a modern engine, propeller, brakes, and internal structure of welded steel tubing that replaced wood and canvas. But it was not strictly a fighter, and Javier, by now a Harvard undergraduate majoring in the history of science, was principally interested in fighters. So they acquired a third replica, a Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a built by prolific replica builder Carl Swanson of Darien, Wisconsin—like the others, a pastiche of antique and modern components.

As he got older, Javier’s interest shifted from the pilots to the airplanes themselves, and he started asking questions like: Were the aircraft very different from what we fly today or were they similar? And how did their designs come about? “So we started collecting really as authentic as we could,” he says. “A friend gave me some very good advice about collecting: ‘Restrict yourself. Make sure that the collection tells a story.’ ”

The story the Arangos chose was the evolution of aeronautical technology during the four years of the war. All the combatants built airplanes at a feverish pace, nearly 150,000 of them, mostly fighters or two-seat reconnaissance aircraft, but nearly all were destroyed in combat or accidents. Designed for brief and often inglorious careers, airplanes were made of impermanent materials. Those that escaped hostile fire and takeoff or landing accidents deteriorated quickly in routine use or in storage.

The hectic pace of manufacture and attrition denied manufacturers the leisure to stand back, take stock, conduct research, and methodically conceive a novel prototype. On the other hand, their techniques and materials allowed new designs to be built and tested in weeks. Engineers improvised. Types came and went by the dozen. The choice by governments of which to procure in large numbers and which to ignore seems to have been ruled as often by caprice as by good sense. Some features that appear prescient from our perspective, like the all-metal construction and thick monoplane wing of the Junkers J.1, got nowhere, while others, such as the pointless triplane arrangement initiated in England and promptly copied in Germany, spread like infections before disappearing as suddenly as they had come.

The Dutchman Anthony Fokker was particularly prolific, once bringing eight different prototypes to a German procurement competition. When one of his offerings was passed over, he modified it overnight, re-submitted, and won. Though he was not a favorite of the German general staff, Fokker found ways to sell his airplanes, exploiting his acquaintance with aces like Oswald Boelcke and von Richthofen, who respected him because he was, like them, a virtuoso pilot. Fokker had a great success early in the war with his Eindecker, the so-called “Fokker Scourge” of the summer of 1915, and near the end with the D.VII, the only fighter of the era to have a noteworthy career after the Armistice.

The Arangos began their quest for authenticity by replacing the modern engines and propellers of the airplanes they had with original ones, and removing brakes, radios, and all the other gear required by modern airports. They moved the nascent collection to the family ranch near Paso Robles, about midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, built hangars, dedicated a 2,200-foot stretch of grass to a runway, and scouted the surrounding fields for emergency landing spots. Here, Javier could fly under conditions similar to those for which the airplanes had originally been built: grass fields, and readiness at any moment for an engine failure and a forced landing. Forced landings have been few—one occurred when a pushrod from a rotary’s cylinder came adrift and began to tear up the cowling—but to avoid tempting fate, the more valuable airplanes are dismantled and put on a truck if they need to make the four-mile trip to the Paso Robles airport.

The Arangos engaged Chuck Wentworth, who had taught Javier to fly the Fokker Triplane replica at Flabob, first to rebuild airplanes and then to build others from scratch. With the help of Wentworth, who incorporated at Paso Robles in 1991 as Antique Aero, the collection grew, acquiring or building a string of Nieuports—models 11, 17, 24bis, and 28—as well as additional Sopwiths and Fokkers. It also snagged a few outliers, including two Blériot XIs—the model in which inventor Louis Blériot had made the first aerial crossing of the English Channel—and a non-flyable pre-war Fokker Spinne, whose Dutch name, meaning “Spider,” referred to the web of wires bracing its warping wings. Recently, it has added a SPAD XIII replica built by Roger Freeman of Vintage Aviation Services, and a Wentworth-built Sopwith Snipe, both displaying the increased strength, bulk, and mass made possible by the Mercedes and Hispano-Suiza liquid-cooled engines that began to replace the lighter but less powerful rotaries late in the war. Two of Arango’s airplanes, the Eindecker (the name means “monoplane”), with a 100-horsepower Gnome, and the Sopwith Tabloid are the only representatives of their types that are accurate and flyable. The collection includes two originals: a 1917 Sopwith Camel that is being restored to flying condition with a 130-hp Clerget engine, and a Blériot built by the Vandersarl brothers of Colorado in 1911.

Aficionados of World War I airplanes form a small but fractious community. They debate authenticity: Is this airplane more or less authentic than that one? What are its shortcomings? What shade of red was von Richthofen’s triplane? Should modern fabric coverings, bolts, and cables be allowed? Is 4130 aircraft steel an acceptable deviation from the mild steel of the originals? Such minute questions arouse surprising passions. “I have seen many very nasty and very personal encounters among these different groups,” Arango says.

Although manufacturers used different techniques for framing and bracing, building a World War I replica from scratch is much like building a balsa-and-silk model airplane. The fabrication techniques were simple, so cabinet-makers and tinsmiths could readily adapt their skills to turning out thousands of airplanes. A proper respect for authenticity requires, however, that all of the work be done in the way it was a century ago.

There is little agreement about the proper use of words like replica, reproduction, restoration, and accurate, authentic, and original. It may seem intuitively obvious that a reproduction built today, no matter how accurate, is not an authentic World War I airplane. Just a few dozen airplanes built during World War I exist, mostly in museums; only a handful still fly. But the matter is complicated by the fact that even the surviving original airplanes have invariably been repaired or restored with various degrees of attention to authenticity. An airplane built today using original plans, materials, and methods might be more historically accurate than a surviving original that has been improperly restored. To further compound the problem, not all original examples of a given type were identical: Thousands were built; they used different engines, different factories adjusted the structures to suit their tools and methods; and when they reached the field, pilots modified them yet again. There is no single definitive Sopwith Camel, Fokker D.VII, or Nieuport 28 against which to measure a modern copy or restoration.

“There are three levels of authenticity,” Arango says, speaking of the 23 airplanes in his own collection. “The original Fokker from 1981 and the first S.E.5, those are the lowest kinds—the lookalikes that you use for movies in Hollywood. The next level is three or four airplanes that were like those, but that we have retrofitted back to nearly their original state. The structure is not 100 percent, but they have the correct engine, the correct weight, the correct aerodynamics, the correct look and sound. The others are pretty much as authentic as we can get.” Arango accepts certain deviations—for safety’s sake, modern seat belts and coverings in lieu of explosively flammable nitrate-doped linen—but the structures, fittings, and engines are correct in every other detail.

As the desire for historical accuracy grew, says Arango, the fieldwork and research required grew with it. For Sopwiths, detailed original plans are still available. Not so for Fokkers. Originals in museums can be inspected and measured to re-create plans. When there are no surviving originals, as is the case with Fokker’s Triplane and D.VI, dimensions must be derived from photographs and construction details inferred from other Fokker products.

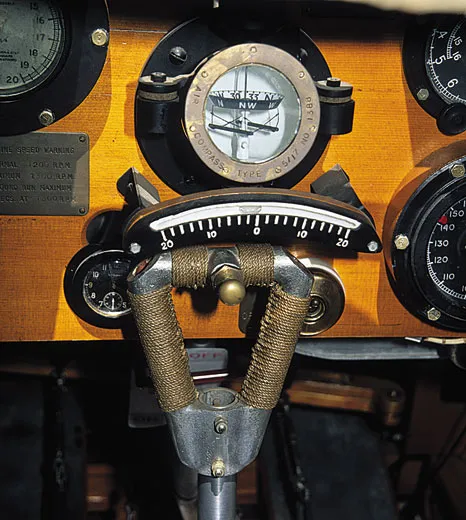

Original instruments and other components can still be found, sometimes in odd places. “You know where we get the magneto switches for the British airplanes? You can go to old British hotels, and that’s the light switch,” Arango says. “It’s exactly the same fixture that they’re using now.”

Engines are a perennial challenge. Arango’s airplanes all have or are awaiting original engines, and all but one is in flying condition. Most of the airplanes in the collection are outfitted with rotary engines. Not to be confused with the modern Wankel-style rotary, World War I rotaries look like radials until they start, and you find that not just the propeller but, improbably, the entire engine spins. One of their peculiarities was lack of a throttle; pilots decreased the power output by cutting the ignition to various cylinders with a “blip switch.” Although these engines were manufactured in the hundreds of thousands, very few still exist. The 110-hp LeRhône, which would be the correct engine for many types, is in particularly short supply.

The collector’s dream is to find, tucked away in the back of a barn, an intact airplane. It seldom happens anymore; the barns have all been searched. But Arango has had that time-capsule experience. “A couple of years ago we got a phone call from someone who said: ‘I know you have these airplanes, are you interested in an engine? It belonged to my father or grandfather or whatever and it’s in a case.’ And the case was the original case. We opened it and there was a 160 Gnome inside—from 80 years ago, untouched.”

Like airplanes, engines can be reproduced to perfection. For several years a Paso Robles machinist, Richard Galli, has been creating for Arango a set of 10 precise copies of an original 110-hp LeRhône. The work generates mountains of metal chips, liberating, for example, a 35-pound crankcase from a 650-pound slug of steel. The manufacture of the required 90 cylinders—an inhumanly tedious task—has been outsourced: They are being hewn out of steel bar stock in New Zealand on computer-controlled machines owned by film director Peter Jackson’s Vintage Aviator Ltd., which reconstructs World War I aircraft.

The ability to fly the airplanes, not merely look at them, is crucial to Arango’s effort to gain insight into their evolution. Contemporary reports of their flying qualities are not always intelligible to a modern aviator. He recounts, “One of the British aces, Albert Ball, flew Nieuports and he flew the S.E.5, and he complained that the S.E.5 is slow. I’ve flown both. There’s good data on the speeds. The S.E.5 is a much faster airplane—so what did he mean?” He may have meant that the S.E.5 was less quick on its feet, less responsive, than the Nieuport, but only a pilot familiar with the flying characteristics of both types would know. Similarly, pilots claimed that the Fokker Triplane climbed “like a monkey,” although its rate of climb was actually average. Like other thick-wing Fokkers, however, it could fly in a more nose-high attitude without stalling than the thin-wing Sopwiths and Nieuports, and the appearance of climbing steeply may have convinced other pilots that it was climbing rapidly.

Each type has a distinct personality in flight. “Some of them, 10 minutes and you get out of the airplanes, your legs are shaking, and you’ve aged,” Arango says. “The Nieuport 11, for example, is so tail-heavy, you have to be pushing the stick all the time. Eventually we put in bungee cords to help. The rudders have no feel, so you end up pushing with both legs and releasing with one. The airplane’s wandering all over the place. If I want the simple, safe airplane, the S.E.5 and probably the Fokker D.VII are the best. They’re comfortable, the engines are quite reliable, they’re stable, especially the S.E.5. One of my favorites is the Sopwith Camel. It’s marginally stable, but if you get to know it, it’s so much fun. It climbs at double the rate of any other airplane, it turns in nothing, it maneuvers—you just think and it goes there—and once you get used to its peculiarities of flying sideways and not doing what you expect all the time, it’s a very nice airplane to fly.”

First flights are always a challenge; the only possible preparation is experience in many airplane types. After taxiing and raising the tail, says Chuck Wentworth, who has made first flights on many of the aircraft he has built, “you just take a big deep breath and go.” The airplanes designed late in the war fly much like airplanes of today; the 1914 Eindecker, on the other hand, is more peculiar, having only movable controls, no fixed surfaces on the tail, and no ailerons (to bank, the pilot uses cables to twist the wings). Even the blip switch is primitive: The ignition is either on or off, full power or nothing. “I put myself into the 1914 mindset to fly it,” Wentworth says. “I don’t expect it to fly like a Decathlon or a Pitts Special.”

Arango, who has written several scholarly articles about the subjective characteristics of World War I aircraft, has begun testing some with modern digital data-gathering equipment, gyros, accelerometers, and force gauges that are now sufficiently compact to fit even in the claustrophobia-inducing cockpit of a Camel. The final results of his scholarship are still to be published, but it already appears that some commonly accepted wisdom—for instance, the idea that the gyroscopic forces of spinning engines powerfully affected maneuverability—may be exaggerated.

Apart from what the collection may in the end teach us, to walk through the Aeroplane Collection hangars is to experience a special mixture of awe and wonderment: awe merely to be in the company of these characters from past dramas, each airplane with its own personality and expression; and wonderment at how little time separated the tentative Blériot and Spinne from the mature and deadly SPAD and D.VII. How in the world, you wonder, did Fokker find his way, in four chaotic years of war, from the rickety Eindecker to the plywood-skin wing of his D.VIII, which would not have looked out of place if you had mounted it on a Curtiss P-40 some 20 years later?

It makes you think too of the young men who fought daily in these airplanes, when each hour was the one in which they might fall, or bleed, or burn to death. The Arango collection reanimates under a California sun a past when, at the clatter of an approaching Sopwith, mechanics put down their tools and strode out to meet the pilot who survived—by skill or luck—another day of war.

Los Angeles-based pilot and aviation writer Peter Garrison designs and builds his own airplanes.