Ode on a Canadian Warbird

The author remembers childhood, with round engines.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06C_DJ10-flash.jpg)

It was impossible to greet the epochal advent of the jet fighter with anything but contempt. I happened to grow up between 1939 and 1945 in a small Canadian town, but any kid born and raised anywhere during World War II knows in his bones that a true warplane wears matte paint the color of mud and swamp water; has exhaust stacks, glycol tanks, air scoops, and a cage-like cockpit; and is pulled ahead by a huge rotating disk. On startup, it snorts awake and coughs and sputters and shoots fire and smoke from its exhaust pipes; the noise smooths into a rising roar on takeoff as the landing gear swings up and it barely clears the tree line. When it comes home to land, its wings wigwag a bit and the tail sinks and the airplane bounces a couple of times on its fat black tires before rolling to a quick halt, emitting one final snort as the prop ticks to a stop.

Where was the romance in a shiny silver pipe that sounded like a vacuum cleaner and flew so fast and so high you could barely even see it? Even today, it's painful for worshippers of warplanes to admit that jets rule the skies and have for half a century.

I doubt I'm the only ex-kid thus frozen in aeronautical time. To have lived through World War II as a boy is to have absorbed a passion for the warplanes hurtling across the skies of Europe and the South Pacific with murderous intent. Their pilots were knights-errant maneuvering for the kill on adrenaline and instinct, furnishing the only glint of glamour in that endless slog of a war. Putting a knight-errant into a jet was like tucking him behind the wheel of a Buick Roadmaster.

A large part of our fascination was that every one of those countless, pre-1945 piston-powered warplane types was so vivid a personality—no two alike. Douglas, Lockheed, Supermarine, Hawker: Each manufacturer stamped its identity on the product—in the shape of the wing and the stabilizer fin, the blunt nose (air-cooled radial engine) or the pointy one (water-cooled in-line), the cross-section of the fuselage. British and American warplanes won our allegiance, in part because kids like me could have been in charge of naming them: Mustang, Spitfire, Hurricane, Thunderbolt, Tomahawk, Flying Fortress, Lightning, Liberator. German kids had to make do with letters and numbers (served them right!): Bf 109 and FW 190. Sinister-sounding Zero aside, Japan's fighting planes were saddled with sissy American-coined nicknames like Betty and Dot.

The media of the day didn't cater to kids; we had to feed our avidity for warplane facts by scrounging information via bubblegum cards, the silhouettes in plane spotter books, magazine photos, movies, and comic strips like Terry and the Pirates, Steve Canyon, and Buz Sawyer. Peer status hung on micro-knowledge: the difference, for example, between a Blackburn Skua (a fighter/dive bomber used by the British Fleet Air Arm) and a Blackburn Roc (an improvement on the Skua with an electrically driven, rotating gun turret).

What a mercy that kids couldn't penetrate the hectic Allied propaganda enough to learn, for example, that the Brewster Buffalo was a big fat hog of a fighter and a sitting duck in combat; that its pilots called the Bell Airacobra the Iron Dog (and not as a compliment); that the majestic-sounding British Boulton-Paul Defiant, its only armament a fixed, forward-firing gun turret amidships, was a kind of airborne Maginot Line; that at least half of all British bombers circa 1942 belonged in military aviation's old-age home even before the war. In a kid's superheated patriotism, anything with wings and a British roundel or American star—or a red Russian star, don't let's forget our Gallant Soviet Ally—was a gladiatorial hero.

The kid bursting with warplane mania needed outlets, so as not to explode. Drawing warplanes was easy, cheap, quick, and satisfying, and turned my bedroom walls into a gallery of aviation art refreshed almost daily. Flying models promised to be even more fun. Building them proved, alas, forever just beyond the skill and patience of a nine-year-old; every attempt to cut and glue all those delicate balsawood ovals and stringers into something resembling a Spitfire or a Messerschmitt exploded in curses and tears long before the glorious realm of rubber-band-powered flight was ever attained. Carving a 25-cent solid model from a rock-hard block of basswood with a paring knife (X-Actos were for the gentry) ended in similar frustration; the result would never even approximate the sleek object on the cover of the box.

To the despair of Canadian lads, some evil pact between FDR and Ottawa blocked the inflow of far superior American-made toys; I can never forget that visiting kid from Detroit smugly flashing a beautiful little plastic B-17 in his palm like the Hope diamond. The tiny Canadian toy industry's conversion to a wartime market produced only a crude metal object, painted an idiotically inauthentic pastel blue or mint green or scarlet, that looked like a Hawker Hurricane only if you held it at arm's length and squinted.

Canada, so vast and empty and safely distant from the European war, was the natural venue for a sweeping emergency program called the British Commonwealth Air Training Scheme. Almost as soon as war had been declared against Germany (Canada beating even Britain to the punch), training airbases sprang up across the country to mold fighter pilots and combat aircrews out of raw British Commonwealth and various other Allied recruits. Three or four such bases lay within a 20-mile radius of my Ontario hometown, the closest a mere nine miles east, near the hamlet of Jarvis. To a war-wild kid of eight, this was better than if they'd plunked down the Great Pyramid of Cheops in those empty fields.

My fondest dream was to get as close as possible to the action of the war— fated, barring some miracle, to remain a dream for a kid stranded thousands of miles from the battlefront. But miracles can happen. One such occurred the day in 1942 when my expat Uncle Gib, a New Jersey doctor and a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Air Forces, stopped by on a family visit. “Kindly Uncle Gib,” I should have said, because he leveraged his prestige to wangle the five McCall boys a tour of the Jarvis Bombing and Gunnery School.

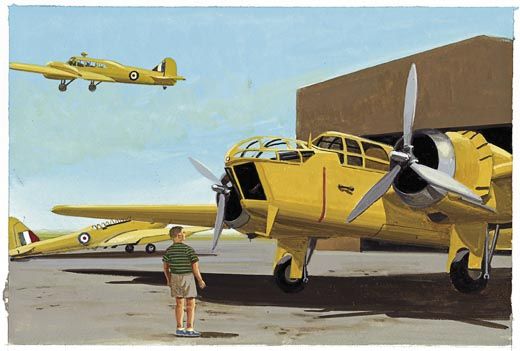

What shimmers brightest in memory from that enchanted afternoon 60-odd years ago was the quiet ecstasy of walking along the tarmac and touching real warplanes with my own hands. I discovered that real warplanes were streaked with oil and exhaust burns, scratched and patched in ways that escaped notice in those glamorous aerial views. Only superannuated types flew at the Jarvis school, like the Fairey Battle, an ungainly fighter-bomber that had almost singlehandedly lost the Allied air war over France in 1940; the Bristol Fairchild Bolingbroke, a variant of the Blenheim light bomber; the Westland Lysander, a gawky high-wing observation plane; and the Avro Anson, a harmless-looking twin-engine bombing trainer. All of the Jarvis aircraft were painted bright yellow like all RCAF training aircraft. But in the eyes of the boy airplane nut, every one was vital in the Allied war effort.

The thrills weren't always static. Our tiny corps of fanatics soon sniffed out the fields near town where student fighter pilots practiced low-level runs. The “Danger: Low Flying Area” signs served only as an invitation to stand out there in the open until an AT-6—Harvard, in RCAF nomenclature—suddenly materialized on the horizon and thundered straight toward us 30 feet off the ground, flattening even the nerviest against the earth as it passed overhead in a mad blur of noise and propwash. Whereupon you got up and did it again and again until the last Harvard had gone home.

My own aviation fever was intensified no end by having a father who wore the uniform of the Royal Canadian Air Force. In 1940, seized by the patriotism common among Canadian manhood at the time, he sidestepped his official exemption as a father of five to accept a commission as a pilot officer. At first, he flew a desk in Ottawa as a press liaison officer—natural enough for an ex-newspaperman, but hardly a stage for war heroics. His kids got over the letdown when Dad was assigned to run interference between the RCAF and the Warner Brothers contingent filming Captains of the Clouds, one of Hollywood's innumerable morale-stirring war movies, this one glorifying Canada's bush pilots and starring James Cagney. The McCall boys would reap near-royal prestige a few months later by showing up at school wearing our brand-new RCAF-style blue flannel Captains of the Clouds wedge caps.

Our RCAF connection next brought us a genuine butter-yellow “Mae West” life-jacket, the very kind worn by Spitfire pilots downed over the English Channel. We never bothered to ask how Dad had acquired this priceless article of the Allied air war. We simply made the most of it, taking turns bobbing about in the local swimming pool wearing that floating pillow while the have-nots stared in envy.

Dad was also assigned to shepherd the young Canadian fighter ace George “Buzz” Buerling across the country on a war bond drive. Dad's diary entries from that tour almost wince in pain: The dashing Buzz, fresh from scoring numerous kills in his Spitfire over tiny, beleaguered Malta, made an unlikely poster boy for the Allied cause. He liked killing people—in their parachutes, if the chance arose—and didn't mind saying so to the Canadian press. Buzz was likely to say just about anything, to my father's horror and the regret of Buzz's RCAF sponsors. (The restless Buerling, who'd known little else in his adult life but air combat, felt adrift in peacetime. He soon hired himself out to the fledgling Israeli air force, only to die in a landing mishap in Cairo in 1948.)

Dad would be posted overseas to the Canadian 6th Bomber Group in Yorkshire, England, in the summer of 1943, and military souvenirs kept trickling into our hands: the gorgeous blue-and-gold cloth shoulder patch of the U.S. 8th Air Force, cap badges of virtually every extant British Army regiment, booklets of tiny paper cutout models of British aircraft requiring a surgeon's touch to fold and glue to completion. The childish greed for such loot obscured any observations of what was happening to our father. Charged with writing daily morale-boosting profiles of Canada's brave young airmen for home-front consumption, he found himself over and over again interviewing one Lancaster bomber crew after another before a nightly raid—wholesome lads, many of them barely out of high school— only to find the next morning that they were never coming back. He lost his best friend this way, shot down over Arras, France, one June night in 1944. The relentless tragedies left him shattered; within six months, he was repatriated and out of the service. I don't think he ever really recovered, nor did his seething hatred of everything German ever cool.

The ugly realities that made the war such an ordeal for home-front grownups seldom penetrated the make-believe world of schoolboys. From a kid's perspective it was all mostly pain- and anxiety-free, a living comic strip that began on September 1, 1939, and chronicled one glorious, uninterrupted winning streak. The weekly movie newsreels verified this: It was only enemy ships that were getting sunk, enemy cities bombed flat, enemy planes knocked out of the sky. Only Allied airplane factories were humming, Allied ladies turning out bombs by the thousands, Allied ships sliding down the slips at an almost hourly rate. So far as you could tell from the carefully censored film footage, the D-Day landings were virtually without Allied casualties. There was Pearl Harbor, admittedly, but Japan had outrageously cheated, so that didn't really count. Only years later did I learn that the Dunkirk fiasco hadn't been a victory for our side.

Well past the end of hostilities with Germany and then Japan, my enthusiasm kept my World War II roaring on. Peace be damned, I wasn't ready to abandon all that hard-won warplane intimacy, or the state of perpetual excitement the war in the air had been stirring in me for what seemed to be my entire life. Besides, what thrills could a world at peace provide in their place? Bank robberies? Four-alarm fires? Stamp collecting?

I decided it didn't have to end after all. Particularly not when, in late 1945, a local farmer acquired a Canadian-built Hawker Hurricane of his very own, through a government program unloading suddenly redundant military aircraft for something like 20 dollars apiece. He parked the Hurricane in a field visible from the highway, to be cannibalized as needed for bits of metal or wire. Propeller and gunsight and a few vital instruments aside, it was all there: the airplane that had won the Battle of Britain! Over the next couple of years, I hiked out to that farm and climbed into that old fighter every chance I got, my every fantasy bout of aerial combat climaxing with my busting open the starboard-side escape hatch and tumbling out of the cockpit and down off the wing, to live and fly and fight another day.

As in a time-lapse film, the Hurricane—my Hurricane—would, over the months and years, gradually disassemble itself until one gray November day in 1949, I passed by that field and confronted an assemblage of skeletal struts and tubing, no longer a heroic fighter, but a rusting set of monkey bars. My World War II had finally ended.

Bruce McCall is a writer and illustrator whose work frequently appears in the New Yorker.