The Underwater Airship

Exploring the wreckage of the USS Macon, which went down off the California coast 80 years ago.

A sudden wind shear hit the USS Macon. The rigid airship was returning from an exercise off the coast of California, carrying a fleet of F9C-2 Sparrowhawk fighters on trapezes inside its belly. The gust was strong enough to tear the upper tailfin from the ship. On February 12, 1935, the Macon was three miles from shore when it sank to the bottom of the Pacific.

The wreckage of the experimental airship sits 1,400 feet beneath the surface, but it does get the infrequent visitor. The site was discovered in 1990, when some items were collected—bottles and plates from the galley, and a few aluminum pieces of the airship’s structure, which were conserved and sent to the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. In 2006, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which manages the marine sanctuary where the Macon rests, led a mission to survey the site. Last summer it was visited by the exploration vessel Nautilus, run by the Ocean Exploration Trust. The crew was on a six-month mission around North America, and offered a day of ship time to NOAA. The agency sent Megan Lickliter-Mundon, who had been an intern in 2012 and wanted to study the Macon wreckage for her doctoral thesis on nautical archaeology at Texas A&M University.

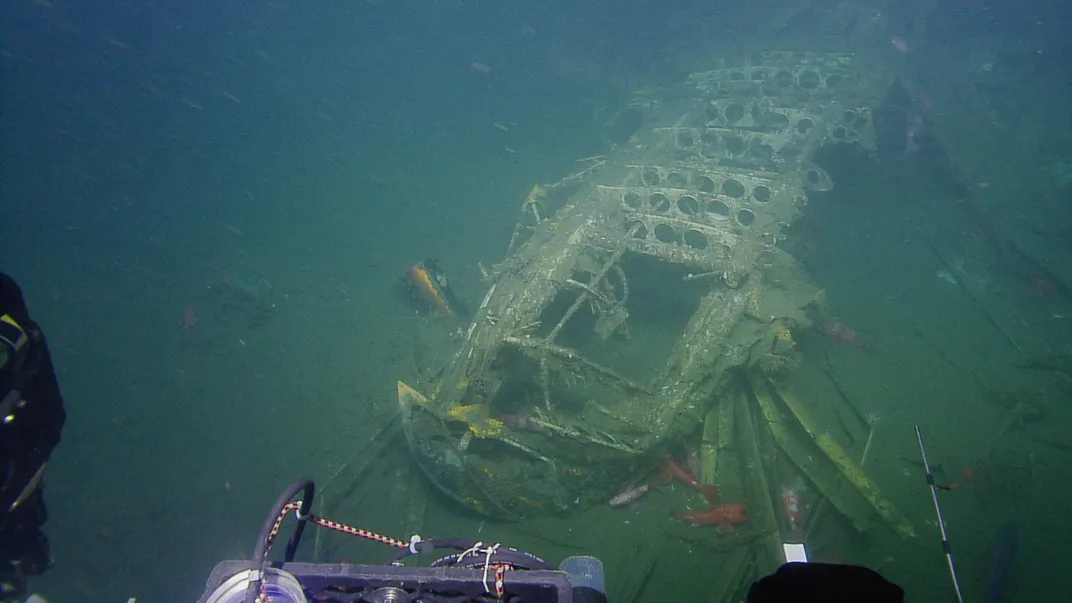

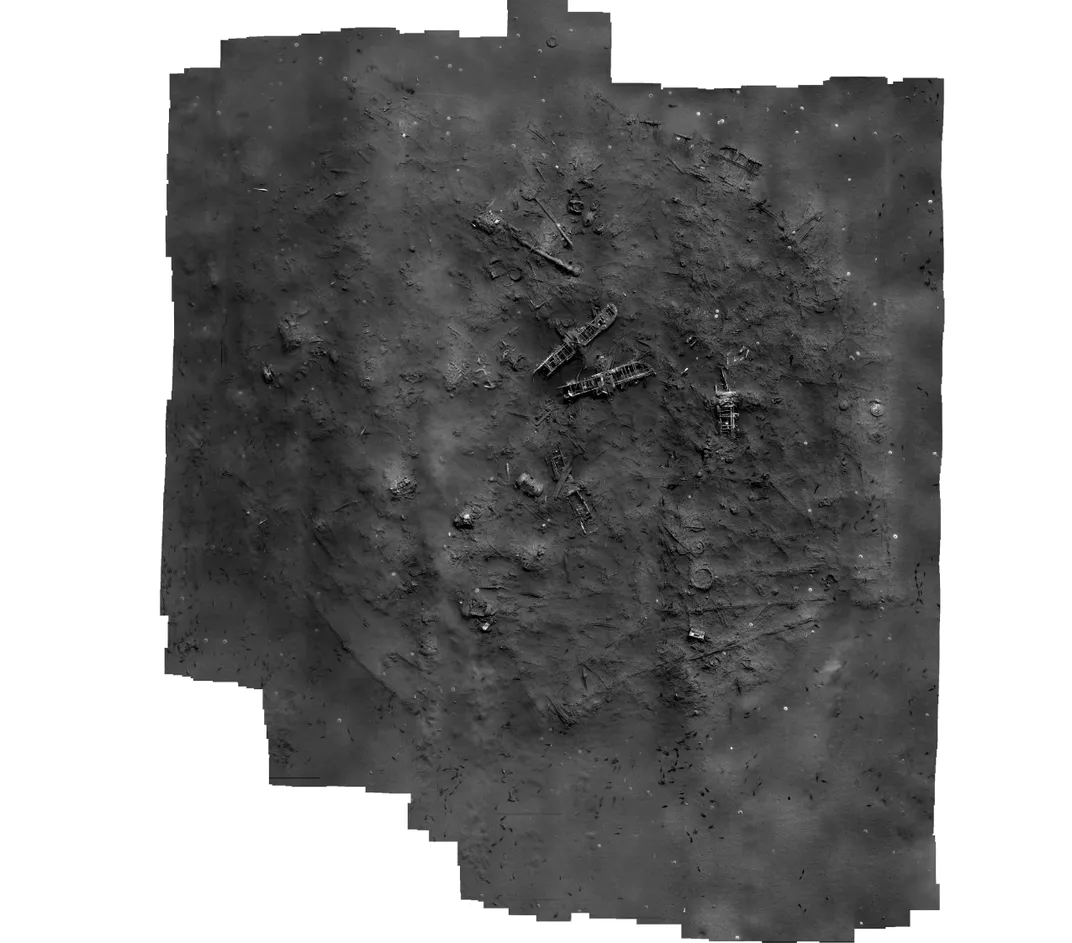

Last August, viewers could watch a livestream on the Nautilus’ website as a remotely controlled vehicle weaved back and forth over the site, recording it with high-definition cameras. When it finished, the vehicle grabbed a piece of the airship to take up to the surface. Lickliter-Mundon brought the aluminum piece to Washington, D.C., where she’s working with the U.S. Navy’s Underwater Archaeology Branch to conserve it and learn more about its decomposition during its 80 years underwater. “The conservation process for aluminum was unheard of [during the 1990 retrieval], so it went through an iron-based conservation process,” says Lickliter-Mundon. “We built the recovery of this expedition around bringing up a sample and comparing it directly.”

By studying the impacts of the different techniques used on the two pieces, specialists in underwater aviation archaeology (a field “in its teenage years,” says Lickliter-Mundon) can start to build a guidebook to care for wreckage sites, some of which are quickly reaching a century old. The Navy, which still owns the Macon and about 14,000 other aircraft wrecks around the world, “has a vested interest in all of its craft that fall under the protection of the Sunken Military Craft Act,” says Alexis Catsambis, a maritime archaeologist with the Navy. That might simply mean monitoring the site unobtrusively, or taking more proactive measures that slow the degradation. When metal is in saltwater, the sodium and chloride ions react with the loose electrons in the metal, creating a weak electrical current that eats away at the metal. One way to slow the process is clipping a small piece of a weaker metal, such as magnesium, to an aluminum girder sitting underwater. The magnesium will give up its electrons easier, leaving the stronger metal largely untouched. Lickliter-Mundon doesn’t know yet if it’s possible to preserve an entire aircraft this way, given how fragile many wrecks are, but she hopes to find out.

In addition to the conservation, Lickliter-Mundon wants to use the photomosaic to learn more about how the Macon sank. When the tail was torn by the wind, helium began venting from the rear section, causing the ship to tilt nose-up. As the crew dumped weight over the side, the Macon rapidly began to rise. Emergency vents popped to equalize the pressure, and the airship descended, hitting the water tail-first. At some point, Lickliter-Mundon says, the airship broke in two; the wreckage reveals that the larger piece carrying the hangar “went down like an accordion, because all the water ballast systems are on the end and…the biplanes are sitting right in the middle of the site,” she says. “They’re completely upright, they’re not really broken, they just settled down…. You can see the Navy insignia on [one]. It’s beautiful.” Unlike the demise of the USS Akron, the Macon’s sibling ship, which went down violently in a storm off New Jersey two years earlier, “it was a very gentle sinking.”