Stranded

Four aircraft, 12 airmen, 25 days, 40 below zero, in the middle of nowhere.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Stranded_0911_10_FLASH.jpg)

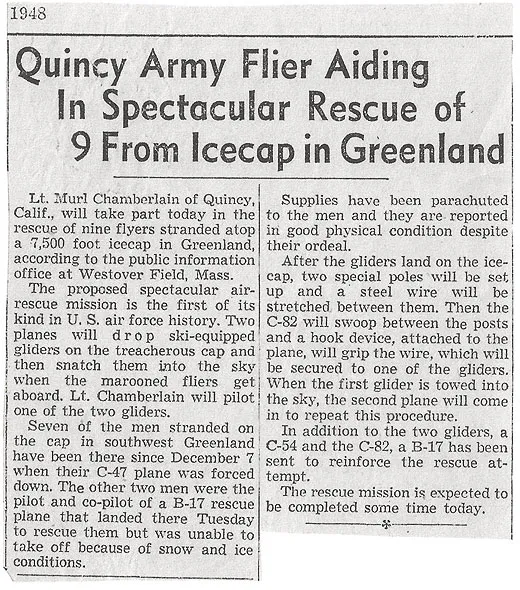

ON DECEMBER 7, 1948, an unusual aviation drama began to unfold. A U.S. Air Force C-47 transport on a routine flight across Greenland got caught in a whiteout and ended up flying into the snow-covered terrain. The pilot sustained head injuries, but all seven men on board survived.

The aircraft went down in southern Greenland, about 125 miles north of its destination, the Air Force base Bluie West One (BW-1). Three days later, an Air Force B-17 attempted a rescue of the downed airmen. But the bomber landed in soft snow and began sinking. Now another aircraft and two more airmen were stranded on the ice cap.

Eventually, a total of 12 airmen ended up in Greenland without an aircraft to get them out. The Air Force turned to the world’s premier arctic rescue organization, the 10th Air Rescue Squadron. The 10th was commanded by the legendary Bernt Balchen, the first airman to fly over both of Earth’s poles and the era’s greatest contributor to arctic search and rescue. My uncle, Murl Chamberlain, a glider pilot with the 10th, was called on to help with the crisis.

When it was over, Murl wrote a longhand account of it that I eventually inherited, along with photographs of the aircraft and people who had been stranded. This article is based in large part on his memoir.

In the 1940s, militaries were starting to use gliders for rescues. Gliders, such as those made by Waco, had been used in World War II for troop insertion and removal. Because they had no engines, they were essentially empty containers that could be filled with people needing to be transported, then picked up via a tow rope by a powered aircraft and hauled up and out. Germans used gliders in 1943 to remove troops from the Kuban peninsula in Russia, and in 1945, Allied gliders evacuated wounded troops from Remagen, Germany. Equipped with either wheels or skis, gliders could be adapted to a wide range of terrain.

My uncle Murl flew the CG-15A, an improved version of the CG-4 troop-carrier gliders made famous in the Normandy D-Day invasion and Operation Market Garden in Holland. The CG-15A could carry 15 soldiers or a light vehicle.

At the time of the Greenland crash, Murl and a few other airmen were at Warner Robins Air Force Base in Georgia, preparing to ferry a glider and its related equipment to Ladd Air Force Base in Fairbanks, Alaska. While they were on the runway, waiting for takeoff clearance, the group received a call from the Pentagon: “We were being diverted to Greenland in order to rescue a downed C-47 on the Greenland Ice Cap,” Murl writes. “[I]n a matter of minutes we were rolling down the runway heading for Westover AFB, Mass.

“Naturally, being a Lieutenant and having the shortest date of rank, I had the honor of flying the glider. I wanted to fly the C-54 [towplane] like the rest of the pilots, but in order to get flying time, the glider was my best bet.”

In the meantime, Air Force aircraft flew over the site, parachuting supplies and portable stoves to the stranded men.

On the first leg of the flight, recounts Murl, “I was the only pilot in the glider…. I had a companion though but he had had no experience in gliders or any type of flying…. All I can remember about him was that he had two stripes on his sleeve and he was very polite. He appeared to be enjoying the ride.…”

At Westover, “we received word about the Troop Carrier Command sending another glider, and that we would all arrive together at Goose Bay, Labrador [Canada], coordinating our activities. The weather was beginning to play an important factor and it looked like we would have problems being able to stay VFR [Visual Flight Rules].

“We left Westover…. The C-54 had a tendency to keep the glider at top redline on the airspeed indicator, and I was constantly pleading to slow down or we might end up losing the glider. As we progressed on our way towards Canada, the weather continued to deteriorate. We were now flying over an overcast and the holes in the clouds were fast disappearing. Night arrived with solid overcast below. At this time I was wondering what kind of weather we had at our destination. The report from the C-54 was that our destination [Seven Islands, in Quebec] had at least 2000 feet and 3 miles or more visibility. I believe we had a small discussion about continuing the flight and all agreed to proceed. I thought about cutting loose when we arrived over the radio beacon at our destination and then about an instrument approach in the glider. One small item was missing. The glider did not have any approach charts. I started asking questions: where the field was located from beacon, what type of obstructions and what the terrain was like? Were there such things as mountains or hills that could get in the way? What are the minimums?…

“My young friend again rode in the opposite seat…. He never sensed the developing problems and I saw no need to tell him. I figured it would be best not to go into details so he could continue to enjoy the ride.

“By the time we arrived over the beacon, there were no holes to let down through. All of a sudden the C-54 started a letdown and I knew then and there we were on our way to making an instrument approach. As we descended and entered the clouds, I thought immediately that the C-54 should turn on their landing lights, thereby, I had a chance of staying in visible contact with the C-54. It worked wonderfully. As we let down the C-54 was just a small silhouette with a circle of light around it. To me, it was a beautiful sight. When we broke out of the clouds, there were hardly any lights to see on the ground. It was practically pitch dark. But in a minute or so, we came upon the airfield and received landing instructions. I asked the C-54 to put the glider on downwind and then I would cut loose. As I pulled the release lever, I felt exalted and I had lost a little tenseness that had built up during the let down. Boy! It felt great to touch down and clear the runway….”

Later, the pilot of the tow airplane, Calvin Jackson, wrote of Murl’s landing-lights innovation: “This was a dramatic accomplishment and the Canadian people on the base lined up to greet the crew. Murl Chamberlain should have received a medal for that dramatic aviation event.”

The following day, Murl and his crewmate flew to Goose Bay, Labrador, arriving on December 16. He wrote: “Later, we found out our counter parts from Troop Carrier Command had aborted and had returned to their place of departure. The weather was a little more than what they could handle.”

The Troop Carrier glider and crew arrived a few days later. “Their attitude was arrogant and very uncooperative,” writes Murl.

“…Their entire attitude was that the 10th Rescue Squadron had no business flying gliders and that they were the only ones that were specially trained for this type of flying. None the less, I believe we gave them a lesson that we could arrive under severe weather conditions, when their pilots gave up and turned tail for home.”

The two units now had to coordinate efforts. “I did not get in on the meetings that took place,” Murl writes, “but when they were over it appeared that the 10th Air Rescue Squadron came up on the short end of the stick. I was now reduced to a co-pilot and a captain from Troop Carrier would be the first pilot. Right off, he let me know that he was in command and that I was his co-pilot. My commander [Bernt Balchen] gave some lame excuse and wanted to know if I went along with what was going on. Under the circumstances I couldn’t or did not want to mess up the rescue, or delay any part of it, because of any disappointment and I had a keen sense of duty that came before my pride. The other glider was to be flown by two lieutenants from the Troop Carrier Command.”

UP AT THE CRASH SITE, the men had perhaps three hours of sunlight each day. The crew of the B-17 rescue airplane used torches and other tools to carve out a comfortable shelter in the ice and survived on supplies air-dropped to them, including heaters. But the C-47 crew decided they should stay in their frigid airplane. “After about six hours,” wrote Calvin Jackson, “one of the [C-47] members…made up his own mind that he was going to die that night. He felt that he had one obligation to go down to the B-17 crew and bid them farewell. He climbed out of his sleeping bag, got dressed, and went down to the B-17 crew apartment, and there he found them with steaks frying, the bar was set up, the place was lined with [parachute] silk as fine as any Arabian tent could possibly be, the radios going, and they were sitting there playing gin rummy as cozy and roast as they would be if they were in their downtown apartment in New York.” The C-47 crewman ran back and told his crew mates what he had found. Eventually, “all of the crew members on the C-47 were in larger shelters and there was an underground community with apartments, everyone rejoicing, and surviving in fine condition thanks to the outstanding work done by the B-17 crew members.”

While the Air Force was mounting a rescue attempt with gliders, the U.S. Navy was trying another strategy. The carrier Saipan was ordered into position off the west coast of Greenland, carrying helicopters (including Piaseckis), for possible use if the gliders failed.

Weather around the crash site deteriorated, but neither of the glider crews was aware of the conditions as they made their way from Canada toward BW-1. The severe weather also kept the Saipan from getting into position.

“[From Labrador], there was around 600–700 miles of flying to reach our destination,” writes Murl. “The captain and I were becoming friends and we were working together as a team. It was much better to have two pilots at the controls instead of one. At least we could spell one another, while the other could take a break.” Though he has no engine and is doing no navigating, a glider pilot has his own flying to do: He must keep the craft above or below the towplane’s wake, and more or less on axis with the towplane’s direction of flight. When the towplane turns, the glider pilot has to match the turn, usually by duplicating the amount of bank. If the glider loses sight of the towplane, the two craft could collide.

“The clouds were forming and we were flying barely above the tops,” writes Murl. “It wasn’t long before we were flying IFR (Instrument Flight Rules). As we entered into IFR, we noticed that ice was beginning to form on the leading edge of our wings and our windshield…making it difficult to see through. The captain was trying to look out the side window and slip the glider a little to the side, in order to see ahead. I found a very small window in the center of the windshield and proceeded to discover how to open it. I finally found the combination and the small window came open with a loud bang. Cold air blasted through but it was the only way we were going to be able to see our tow aircraft. Things started to take a turn for the worst, the ice continued to build and the glider was not equipped with deicing equipment. Matter of fact, the aircraft was not intended for weather of this kind. I believe about this time the C-54 thought it best that we descend to a lower altitude. We started a letdown, trying to find a safer place where we could get away from the ice.

“I looked at that tow rope and thought, ‘If I could only crawl to the C-54 and had a chance of making it, I certainly would do so.’ But that was a fleeting thought, and I knew that I had no chance what so ever of accomplishing such a feat….

“It appeared that we were about to buy the proverbial farm; therefore, it was to our best interest to prepare for the big event, or try to stop the transaction if at all possible. At this time, I got out of my seat to go back into the fuselage of the glider to check on the life raft, that had been put aboard in case we had to ditch at sea. The life raft was rather large and it would have been a big job in order to discharge that raft out the side door, pull a lever to fill the raft with air, and then make sure the raft stayed around until both of us could get aboard. I realized that our chances were very small [even] if we could accomplish this task. The life raft was large enough to accommodate 10–12 passengers…. We would have to be extremely careful not to pull the air lever until the life raft was outside….

“I checked everything over and then returned to my seat, saying nothing about what I thought to the captain. As I put my headset back on and buckled in, the captain was upset about something. He said that the C-54 [crew] are considering cutting us loose because the weather ahead was forecast to be below minimums and they didn’t have the gas to return to Goose Bay towing a glider. He became completely irrational and dove the glider and pulled the nose up rather sharply and let go of the controls. This maneuver put a lot of slack in the tow rope and eventually in a few moments there would be a sharp jerk. I grabbed the controls and put the glider’s nose down and tried to minimize the jerk that was milliseconds away. We survived this maneuver and I asked, ‘What in the hell are you thinking about?’ All he said, ‘What’s the use, they are going to cut us loose anyhow.’ I shouted back, ‘We’re going to hold on as long as possible! I am not giving up that quickly!’

“We were now skimming along the top of the water not more than 200–400 feet above. The ice had melted, but that ocean was rough looking with many white caps present. The weather reports started to improve and it looked like we might make our destination. There was no more talk about ditching at sea, and we were beginning to feel that maybe we could survive another day.”

Finally, the glider released from the C-54 and landed at BW-1. Writes Murl: “I must say the ground felt so good that I could just kiss the ground and feel the soil and snow sift through my hands….

“A few days later, the other glider made the trip without many problems. The weather at BW1 was VFR. For some reason or another, the second glider flew directly to the rescue sight [sic] and proceeded to land near the downed aircraft,” even though the snow was very soft.

The Troop Carrier glider was readied for a rescue pickup. “Since this glider did not have skis on it when it touched down on the snow,” wrote Jackson, “it was noticed that the wheels penetrated the snow surface and the bottom of the glider became like a toboggan on a snow surface. Recognizing this, we instructed the ground crew to place large sheets of plywood…in front of the wheels to give a little platform as it started out.”

To prepare a glider for pickup by a towplane, the crew would place a loop of nylon rope between two eight-foot-high poles set about 10 feet apart. The glider was positioned about 250 feet away, pointing toward the poles. A nylon rope attached the loop to the glider. The towplane would fly low and, with a hook trailing from the back, catch the loop, pulling the glider up.

During the first attempt, the heavily loaded glider’s wheels dug in and the rope broke. The glider crew reset the bridle and removed the glider’s wheels, so the glider would slide on its belly. After an hour and a half, daylight was fading and the C-54 made a second snatch attempt.

Again, the towplane made a long run and snagged the bridle. This time the glider had frozen to the ice and would not move. The tow rope broke, then snapped back toward the glider, sawing into one of the wings and breaking off the horizontal stabilizer. The glider’s nose was also damaged.

The second glider, back at BW-1, was prepared for a Christmas Day attempt. “Our glider was stripped of all unnecessary equipment, including the landing gear,” Murl writes. “…Needless to say, I became excess baggage and the captain was elected to try the rescue attempt.” The glider was flown out, and Murl stayed behind at BW-1.

The second glider arrived at the site and was loaded with the stranded men. “I’ll never forget that rescue attempt,” said Edwin Thomson, one of the airmen, in a 1995 article in Yankee magazine. “It was on Christmas Day, and we were finally picked up successfully in the glider only to have the towline break when we were 500 feet up—half a ton of nylon rope snapped back like a rubber band…. I still marvel at how the pilot crash-landed us safely.”

By this time, the world was watching the unfolding drama. Major newspapers covered the events in painstaking detail. “Glider Rescue Attempt Fails; New Methods Are Sought,” one article was headlined; another: “Fliers Stranded On Greenland Ice Cap Will Have Yule Turkey Even If Rescue Fails.”

Finally, after the two glider failures, the Air Force asked Lieutenant Colonel Emil Beaudry, an expert on arctic flying, to bring the airmen out. Beaudry and his copilot, Lieutenant Charles Blackwell, took off from Sonderstrom in west Greenland in a C-47—at last, an aircraft with skis was being deployed to the scene. It also had jet-assisted-takeoff (JATO) bottles. Flying over six hours during a day with only three hours of daylight, the pilots arrived at the crash site early on December 31. All the survivors boarded. The C-47 took off, climbed, and headed south.

After a stop at BW-1 and another at Goose Bay, the aircraft headed for New York City. It was a typical sleet-and-rain winter day when the airplane landed at La Guardia airport. Over 200 press photographers snapped pictures as the men deplaned.

The drama was over.

IN HIS ACCOUNT, Murl criticizes a number of aspects of the rescue mission: “Col. Bernt Balchen, our 10th Air Rescue commander, was very, very late arriving in the area. By some of his statements it appeared that he did not want to take charge. He might have been afraid of losing his reputation, or maybe the Pentagon would not release full control to him. Therefore, we lacked leadership to control all factions of the rescue mission, at the scene of operations.

“We had our prima donnas among our own in the Air Force. Troop Carrier acting up and then taking the initiative to land a glider at the crash [site]. It appeared that did not come from any higher level than within the Troop Carrier personnel involved in the mission. No coordination at all with anybody. If someone had studied the photos of the downed aircraft, especially the B-17 [which had sunk in snow], the glider that first attempted the rescue might have fared better. The photo indicated soft snow, whereby, if the landing gear had been removed, their attempt might have been successful. Also ski gear from the States could have been ordered and been ready when the gliders arrived at BW1…. All these ingredients were building into one big mess, but by some miracle, we had a happy ending.”

Though he never made it to the crash site, his participation in the Greenland mission made Murl the Air Force’s highest-time glider pilot. He went on to have a substantial career in aviation. He continued to fly rescue, mostly in helicopters, through the Korean War, and then B-47s. He concluded his flying career teaching Army pilots to fly helicopters in the Vietnam War. A humble man, he didn’t want his experiences published before his death. In the last month of his life he told me that while he’d had a rewarding career, he’d never been awarded anything more than “a few air medals.” I pointed out that he’d taught me years before that only in the movies does a hero get to save the world. In the military, all we get is an opportunity to do our job, and if we all do our jobs better than the opposition, we all prevail, together.

Murl Chamberlain died on January 10, 2009, at the age of 87. The four aircraft remain in Greenland.

Edward J. Farmer is an engineer and businessman with 40 years of general aviation flying, including gliders.