Where the War Began

A new aviation museum preserves Pearl Harbor’s past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/war-388-sept06.jpg)

The first time I got a good look at Ford Island, in Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor, was through the left windscreen of a Cessna 172 on April 23, 1987. I was a member of the Hickam Air Force Base Aero Club, and I was getting checked out in the Cessna by my flight instructor. We entered the landing pattern above the short runway that bisects Ford Island. Though I was busy with throttle, flaps, and radio, I recall spotting the submerged battleship USS Arizona, now a memorial to the ship’s 1,177 crewmen who lost their lives in Japan’s surprise attack on the morning of December 7, 1941. I am a retired military pilot, and coming in at 1,000 feet, I could imagine how easy it was for the Japanese dive bombers and torpedo airplanes to strafe the U.S. naval air station below.

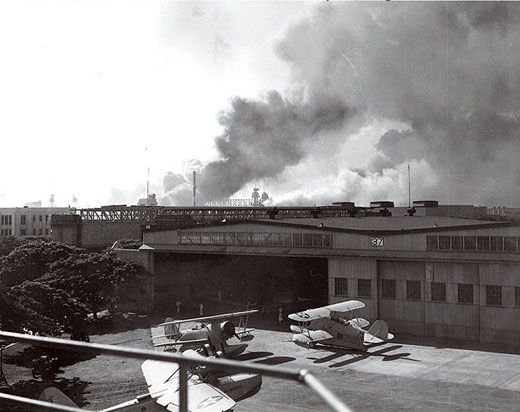

Last September, I was able to see Ford Island up close, as a guest of Allan Palmer, executive director of the soon-to-open Pacific Aviation Museum, which comprises much of the historic air station: an orange and white control tower and three of the surviving hangars. Hangar 37, the first building to be restored, is scheduled to open December 7; it will house several exhibits about the Pacific air battles that took place in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Hangar 37 will offer amenities that many aviation museums do—a gift shop, food court, flight simulators, and theater. But only at the Pacific Aviation Museum can visitors see the scars of December 7: a bomb crater, strafing pockmarks on concrete ramps and taxiways, and the remnants of two hangars that didn’t survive the attack.

Palmer, a former fighter pilot and Vietnam veteran, escorted me to the front of Hangar 79, an 87,750-square-foot building that will eventually house the museum’s Korean, Vietnam, and Cold War exhibits (the collection includes everything from a North American F-86 Sabre to a Bell UH-1H helicopter). Weeds have sprouted through cracks in the tarmac, and the facility is in need of repair. Pointing to green window panes on the hangar door, Palmer asked, “See the bullet holes?”

Japanese strafing runs had left the glass panes full of holes. Several other windows looked as though they had been broken by vandals. “We’ll replace the broken panes and those that don’t have the original green tint, but leave the ones from the attack as they are now,” said Palmer.

Palmer drove past the museum’s other two hangars, which will eventually house exhibits. He pulled up a short distance from yet another hangar, still used by the Navy.

“Here is where the Japanese began their attack the morning of December 7,” said Palmer. “The Navy’s patrol bomber squadron was located here. The Japanese wanted to bomb the seaplanes on the ramp first, because they were the only aircraft that could find [Japan’s] carriers, so it was number-one priority. In photos from that morning, you can see a plane burning right over in that direction.” We walked a few yards closer to the hangar. “Here’s the evidence,” he said, pointing at the ground. Two lines of golfball-size holes had been gouged in the asphalt. “The pilot was probably in a bank when he fired,” said Palmer. “The machine gun on the [outer] wing made that pattern, and the [inner] wing’s bullets hit first, over there.” Two distinct strafe patterns were visible, one ahead of the other. I glanced up into the clear blue sky and imagined a Zero in a slight left bank, wings sparkling as the pilot fired his guns.

The next day, I drove to the museum’s main office, temporarily located in Honolulu, and met Mike Wilson and Syd Jones.

The son of a test pilot, Wilson is the museum’s curator. He had the opportunity to experience aviation first-hand as a commercial pilot before working in the restoration department of the San Diego Air & Space Museum. He joined the Pacific Aviation Museum in June 2005 and takes pride in historically accurate restoration. “Neanderthals in Speedos” is how he refers to improperly restored aircraft. “You wouldn’t put up with mistakes like that in a natural history museum,” he said, “but it happens all the time in air museums.” Wilson’s responsibilities involve planning exhibits and verifying the historical accuracy of everything associated with the collection’s aircraft.

Jones is the museum’s restoration director. He used to work for Tom Reilly Vintage Aircraft in Kissimmee, Florida, where he helped restore warbirds, including a Boeing B-17 and several North American P-51 Mustangs.

Inside a warehouse at Honolulu International Airport, some of the Pacific Aviation Museum’s treasures await transport to their new home. A Stearman N2S-3 Kaydet, covered with a polyethylene sheet, looked as clean as it must have on October 15, 1942, when it rolled off the factory line in Wichita, Kansas. This particular Stearman, serial number 07013, was flown by a future U.S. president. In December 1942, 18-year-old Navy aviator George H.W. Bush flew a solo sortie in the airplane. Years later he recalled his feelings about flying another Stearman: “I was a little scared at first, but the plane was forgiving, and I made it through,” he wrote to a reporter for this magazine in 1994.

From the warehouse, Wilson and Jones led me to an atrium inside the airport. There, in a splash of sunlight, hung an Aeronca 65TC monoplane trainer. Built before World War II, the Aeronca was airborne during the attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, the trainer was operated by the Gambo Flying Service, and a Gambo flight instructor was teaching his son to fly when a wave of Zeros swept past. It wasn’t until after the father and son landed at what is now Honolulu International Airport that they realized the Aeronca’s tail had been shot up, damage that is still visible.

During a phone interview after my visit to Ford Island, Palmer tells me that his aircraft wish list includes “certainly anything Japanese theater. A Val dive bomber comes to mind first. There just aren’t very many of those. There are one or two still in jungles here and there. But then there’s things like Corsairs, P-40s, Hellcats, Betty bombers. We’ll acquire as many of those as we can.” In the meantime, Military Aircraft of Riverside, California, is making a full-size fiberglass replica of a Curtiss P-40 for the museum’s Pacific theater exhibit.

Palmer is most pleased with two recent acquisitions: a Japanese Zero fighter and a Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat, “two really centerpiece airplanes that were major combatants during the Pacific campaigns of World War II,” he says. The Mitsubishi-designed Zero A6M2-21, built under license by Nakajima, was the same type of fighter that attacked Pearl Harbor, although the museum’s Zero rolled out of the factory a year later, on December 14, 1942. This Zero was based in the Solomon Islands, where it flew against American fighter squadrons, including the U.S. Navy’s VF-17 “Jolly Rogers,” Greg “Pappy” Boyington’s VMF-214 “Black Sheep,” and the Cactus Air Force of Guadalcanal. More than 20 years after the war’s end, Bob Diemert, a pilot and aircraft restorer, recovered the Zero on Ballale Island in the Solomons and took it to Canada, where he rebuilt it. Diemert later sold the Zero to the Commemorative Air Force, which flew the graceful fighter at airshows for 10 years. Of all the aircraft in the collection, the Zero might be Palmer’s favorite. “It’s a real ‘wow’ factor for people visiting here, particularly the Japanese,” he says, “because they can see something that’s been recovered, and is here where it all took place. They can stand out there in the grass near the cracks in the concrete runway and kind of imagine all of this going on all around.”

The museum’s F4F-3 Wildcat was manufactured in 1943. The U.S. Navy accepted the fighter on April 3 and assigned it to the aircraft carrier USS Sable. It’s possible the Wildcat and the museum’s Zero could have tangled in a Pacific battle or two had the Wildcat not crashed in Lake Michigan during a training flight on June 21. The F4F-3 never saw combat and had only 150 hours on it when John Dimmer brought it out of the lake in 1991 and restored it to flying status. The Wildcat was on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle when the Pacific Aviation Museum purchased it from Dimmer last December.

In addition to the Zero and the Wildcat, Palmer has rounded up a Douglas C-118, a McDonnell Douglas F-15, a North American SNJ-5B, and a Soviet MiG-15, among other aircraft. These artifacts will no doubt draw a steady stream of aviation fans, but the real attraction of the Pacific Aviation Museum is its historic Ford Island setting.