Psyops: Weapons of Mass Instruction

A Vietnam memoir from the author of Forrest Gump.

:focal(776x209:777x210)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/43/b0430932-dbf2-42d1-a05e-6655de9bbda5/adventures-inpsyops-full.jpg)

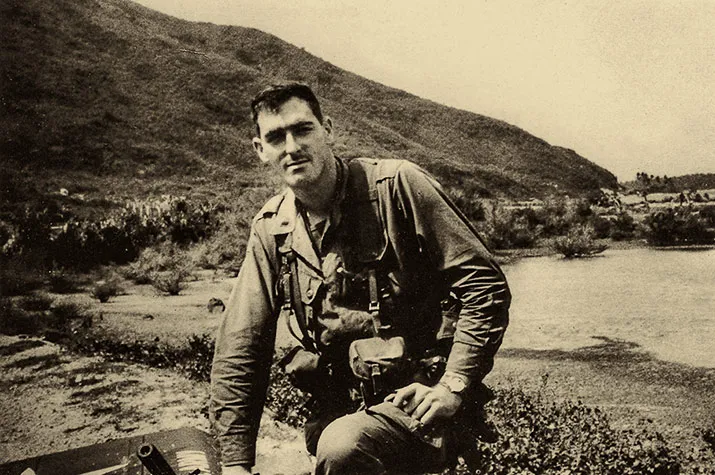

It was mid-July 1966 when I found myself on the edge of a typhoon 500 miles east of Okinawa, wondering just what in hell I had let myself in for. The swells were 40 to 50 feet, higher than my cabin aboard the USS Gaffey, a World War II-era troopship that was carrying my Army psychological warfare detachment to Vietnam. Unlike many of the thousand or so souls on board—including a battalion of the First Air Cavalry Division—I wasn’t seasick, but I certainly felt the straining vibrations through every inch of steel on the ship as it crested each wave.

I was a 23-year-old second lieutenant fresh from advanced training at the Army’s psychological warfare school at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. For three months, they had taught us every dirty trick in the books, and some not so dirty, and others not even in the books. My age and lowly rank notwithstanding, my impression was that I was headed for some exalted position worthy of a John le Carré novel.

Needing fresh air, I went up to the mess hall, where those who could were clinging to tables and those who couldn’t had their heads in various pans and pails provided by the messboys. For the voyage over, I had been assigned “extra duty” as the ship’s “rumors control officer,” so after I’d had my fill of fresh air, I joined an unfamiliar group who were sizing up the seas and quietly started a rumor that an enemy sub was following the ship. Then I returned to my cabin to see how long it would take for the rumor to get back to me.

A week or so later, we landed at Cam Rahn Bay, Vietnam, and were trucked north to Nha Trang, which, during the huge U.S. military buildup of 1966, was a hive of activity, with Army trucks and airplanes relentlessly disturbing what must have once been a peaceful, lovely city on the South China Sea. My destination—along with the destination of 50-odd enlisted men I’d commanded on the way over—was the 245th Psychological Operations Company, which served the II Corps area in Vietnam’s central highlands, site of some of the most savage fighting thus far in the war.

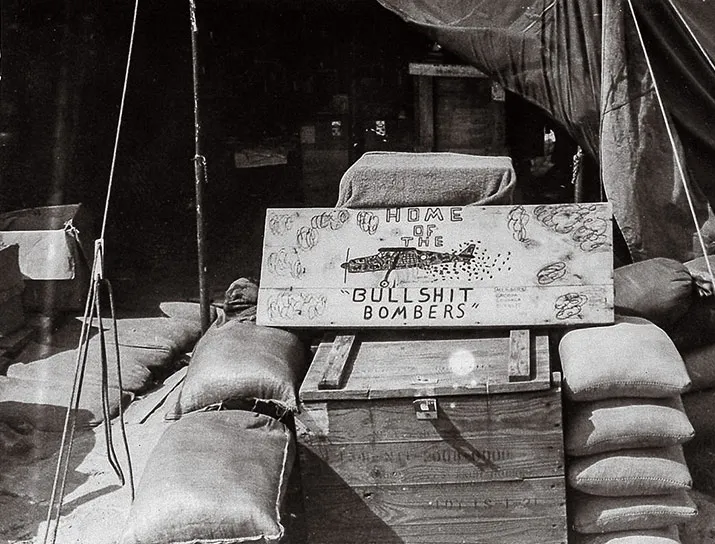

Nobody seemed to be expecting us, nor knew what to do with us. Members of the unit found some tents and told us to set up camp at the edge of a rice paddy near the town dump. If that wasn’t bad enough, it turned out this was the area where daily they burned the contents from the officers’ latrines, and the foul black smoke engulfed our encampment. I was living with some officers in better quarters, but clearly this wouldn’t do, and by the time I got it straightened out, I was told by the 245th’s commanding officer to report to the main psychological operations in command in Saigon for further instructions.

Once there, I was informed that the building had recently been bombed by Viet Cong terrorists. There was nothing for me to do but report in every morning. After I made my report, I was on my own. Thus I spent every day for the better part of a month (courtesy of a college friend) playing tennis at the Cirque du Sportif, a swanky kind of country club in the middle of Saigon left over from French colonial days.

Evenings I spent dining at the rooftop restaurant of the once-fashionable Rex Hotel, watching flares fired by units of the 25th Infantry Division to attract or deter the enemy—I was never sure which—on the far outskirts of the city. I was still wearing my “Psychological Warfare” shoulder patch from Fort Bragg days, and other officers seemed to look at me as if I were some kind of spook or a character from a Graham Greene novel—or so I thought then. Looking back now, I realize they probably thought me a fool—but all that was about to change very quickly.

One day when I reported in at headquarters, orders had arrived from the 245th, assigning me as the leader of a psychological warfare field team with the 1st Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division, operating from a fire base in Phu Yen province, near the town of Tuy Hoa (pronounced “tooey wha”). The brigade, about 4,000 strong, was operating separately from the division, conducting Operation Seward, to protect the rice harvest along the coastal plains, and beyond that, patrolling in the mountain valleys for units of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

The day I arrived at the 1st Brigade headquarters, there had been a terrific firefight the night before, a little ways up Highway One, which ran the length of the country. A large force of Viet Cong had attempted to overrun one of the brigade’s artillery bases, and troops on both sides had been injured and killed. The brigade had only recently arrived in Vietnam, and this was its first big fight. Everyone was terribly upset at the American casualties.

My field team was a sergeant and three enlisted men: two of specialist class rank and one private, who was my jeep driver. They had arrived before me and set up shop in an eight-man tent by the barbed wire on the edge of a large rice paddy that was a respectful distance from the latrine.

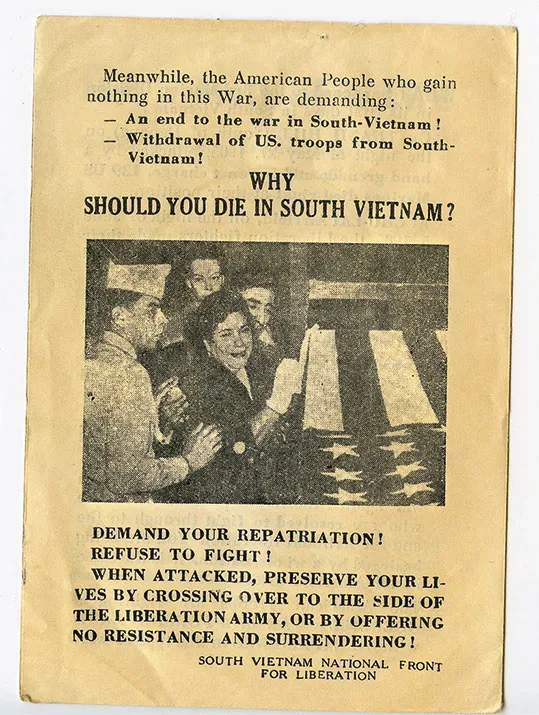

Our equipment consisted of a powerful loudspeaker of the kind used in football stadiums, which could be carried on the operator’s back. Another team member backpacked the 40-pound load of batteries that kept the speaker going. Our gear also included a tape recorder and a number of Vietnamese language tapes that directed the enemy to surrender. The idea was that when one of the U.S. battalions engaged with the VC or North Vietnamese regulars, my team would be helicoptered to the site of the fighting and begin broadcasting surrender demands. In addition, one of the several English-speaking Vietnamese interpreters assigned to the brigade would be made available to us for conveying gentler messages.

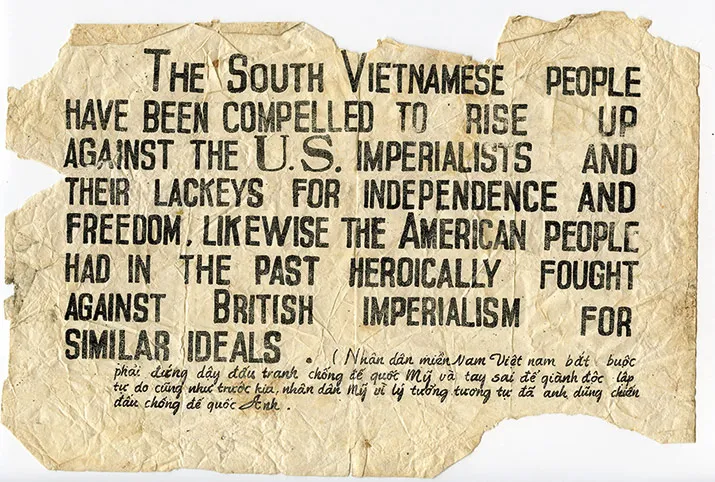

In the meanwhile, my job was to see that appropriate propaganda leaflets were dropped at every occasion. For instance, a report came in from one of the platoons patrolling in a remote valley that North Vietnamese soldiers were stealing chickens from the villagers’ coops. Using the brigade’s secure signal facilities, I teletyped (“twixed”) this information back to the 245th in Nha Trang, along with the coordinates of the village, which I plotted off a map, and by the next day a U.S. Air Force AC-47 would arrive over those coordinates and its crewman would toss out tens of thousands of leaflets to that village and others nearby informing them the NVA were a bunch of no-good chicken thieves and should not be supported in any way, shape, or manner.

At some point during this period, higher headquarters ordered that the word “warfare” be dropped from our title, and our job became psychological “operations,” probably for the same reason that after World War II, the War Department had been renamed the Department of Defense—it sounded less bellicose.

We were also told by the brigade’s intelligence section that the communist forces had an especially high regard for propaganda and psychological operations, and thus if we were taken prisoner, a price would be put upon our heads. They suggested that we exchange our psychological warfare shoulder patches for the ivy cloverleaf insignia of the 4th Division, which we were happy to do, since the division had a long and glorious history during World Wars I and II, and we didn’t want to have our heads chopped off.

***

To win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese, I had another tool at my disposal: an airplane. Designated a U-10, the Helio Super Courier was especially designed for psychological operations. It was a STOL (short-takeoff-and-landing), high-wing, single-engine two-seater complete with an Air Force lieutenant pilot, as well as a compartment in the back for large boxes of leaflets, plus fittings for our powerful loudspeaker.

We flew missions almost every day weather permitted, circling low over targeted villages, heaving out leaflets like tickertape at a parade, and broadcasting messages in Vietnamese to soothe the savage breast. Occasionally we were shot at, and after one flight, bullet holes were found in the U-10’s tail and rudder. Most of the leaflets were made up by the psychological operations geniuses in Nha Trang or Saigon, based on various intelligence reports and the machinations of authorities much higher than me. However, I got to make up my own leaflets if I pleased, and have them printed and delivered for distribution by the faithful U-10, which had only one speed: It taxied, took off, flew, and landed all at approximately 40 knots (46 mph).

On the U-10 missions, I would bring a map or get with the pilot beforehand to give him coordinates. He had a map with a transparent acetate cover on which he would circle the coordinates with a grease pencil.

A lot of leaflet drops were in triple canopy jungle or wooded hillsides where someone—maybe Long Range Patrols or one of our infantry companies—had reason to believe an enemy was present. We also kept boxes of stock leaflets beneath our cots and stacked up to the top of the tent to use if we needed to move fast.

We were never certain whether the leaflets hit the target, unless it was a village you could see from the air. The drop was usually from about 2,500 feet, unless we were being shot at.

The pilot sat with the map in his lap, making educated guesses as to whether we were over the target. Heaven only knew if he was right; all we saw was miles and miles of green jungle interspersed with rice fields or mountains. When he thought he was at the correct spot, he would bank toward the target to make it easier for me to reach back and begin throwing handfuls of leaflets as we circled. After either I or one of my men tossed the leaflets, you could see them fluttering down.

I dimly remember one of the infantry platoon leaders telling me over drinks in the tent that passed for an officers club that the North Vietnamese soldiers were using our leaflets as toilet paper—his men had stumbled on an area in the jungle littered with the evidence. This led to us discussing a plot to embed the leaflets with itching powder or some other unpleasantness, but nothing came of it.

We also had, at our disposal, an AC-47 “Gabby” aircraft—a twin-engine Douglas DC-3 in civilian life. We used it to circle above the enemy’s suspected hiding places and play scary funereal music over the loudspeakers to cause them to run away in terror or at least to keep their troops awake all night.

If the weather conditions were just right, some of these airplanes were equipped with a kind of movie projector that would shine big dragons or other frightful things onto low-hanging clouds. A downside of these tactics was that they could cause any friendly South Vietnamese troops in the neighborhood to run away also.

An added stratagem was for the Air Force to follow the Gabby ship with a Douglas C-47 Spooky airplane equipped with three General Electric mini-guns, which could fire at the terrific rate of 100 rounds per second. Circling at 3,000 feet, a Spooky (also known as “Puff, the Magic Dragon”) could put a 7.62-millimeter bullet into every square yard of a football-field-sized area in less than 10 seconds. Needless to say, the enemy below did not welcome this development.

***

The brigade fire base was a tumultuous place, with helicopter, airplane, tank, truck, jeep, foot, and armored personnel carriers constantly bringing people and taking them away. The battalions were always rotating into and out of the field, except for a sort of palace guard that stayed to protect the base and the enormous tent that contained the Tactical Operations Center, or TOC, which was the focal point of all brigade-related matters great and small.

Here the daily briefings were held, amid rows of maps belonging to the operations and intelligence sections. Banks of radios connecting every aspect of the operations were constantly blaring or hissing, or both, at the assortment of officers and non-commissioned officers who manned them.

Presiding over all this was the brigade sergeant-major, who had built a huge chair at the far end of the tent, which he occupied like a king on his throne. Inside the TOC and out, the expression “Sorry about that” (a phrase from the popular 1960s TV comedy “Get Smart”) was repeated approximately 10,000 times a day by everyone from privates to the commanding general himself.

Half a dozen times, we received word that a unit in the boondocks had made contact with the enemy and our field team was desired at the scene. But in every case but one, before we could get our gear to the helipad, the enemy contact was broken. The one exception was on Christmas Eve, when a rifle company got into a fight with an NVA force of unknown size in a steep valley near a river. We arrived at the place and trudged forward to the sound of guns when suddenly we saw armed men coming toward us.

They turned out to be our men, who were pulling back because an artillery strike had been requested. The contact, however, had been only about 100 yards ahead, well within broadcasting distance of our speaker, so we set up and commenced to play tapes telling the enemy to “Lay down your arms,” “Surrender, and you will not be harmed,” etc., etc. Then the artillery strike came in, and the shells bursting changed the mind of anyone who had been tempted to surrender. The enemy high-tailed it out of there and probably didn’t stop, in the words of the company commander, “till their asses got all the way back to Hanoi.”

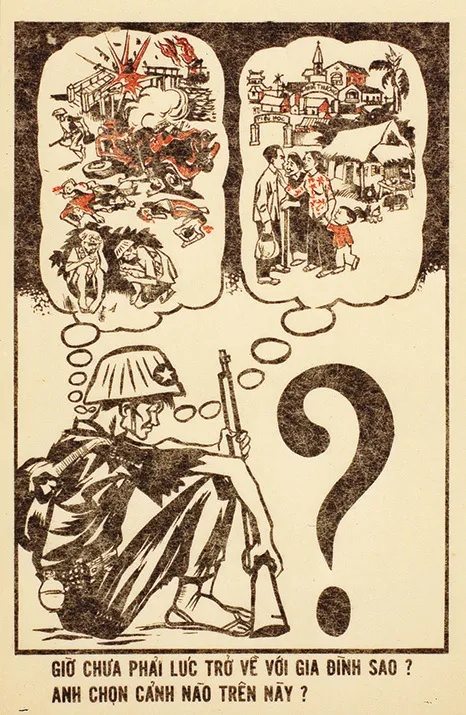

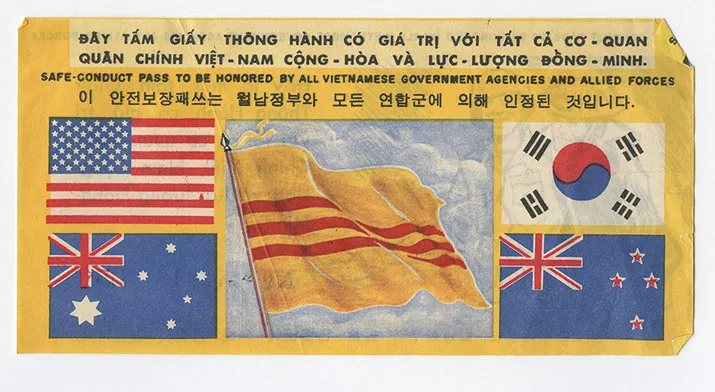

Judging the propaganda’s effectiveness remained difficult. If the subject was broached during any enemy interrogations, the answers were never shown to me, and the spooks doing the interrogating didn’t want me interfering with their conversations. One measure to judge by, however, was the “Chieu Hoi” pass. The Chieu Hoi (pronounced “chew hoyee,” meaning “open arms”) program was a U.S.-backed South Vietnamese effort to promote enemy defections. A “safe conduct pass,” a bit smaller than a dollar bill, promised the holder that he would not be harmed if he surrendered. They were distributed in the countryside by the millions. Sometimes the passes were found in the belongings of enemy soldiers who had been killed or taken prisoner, proving that they’d been at least thinking of giving up.

Not long after Christmas, our psychological operations came to an abrupt halt. It was winter—monsoon season. It rained day and night, a cold, violent, windy rain coming in off the South China Sea. Sometimes it rained so hard we could not see the flagpole in front of the TOC. Out in the field, mud indescribable in volume seized up troop movements, and heavy vehicles could not be used except on roads. Naturally, nothing flew.

For six long weeks, everything and everyone stayed damp or outright wet. No place was dry except the cockpit of the U-10. I would go and sit there alone and smoke a cigarette, sometimes joined by the pilot, who I discovered had been in his college’s chapter of my fraternity.

Then one morning in March, the rain simply quit. On that day, word came down that the brigade was pulling up stakes and moving more than 100 miles inland, over the mountains, to the 4th Division’s main base camp at Dragon Mountain, northwest, near the town of Pleiku. During the monsoon season, the communications system had worked only sporadically; now it was not working at all—all of my “twixed” queries about what I was supposed to do went unanswered. The brigade S-3 (operations officer), whom I reported to, said we ought to go along with the brigade to Dragon Mountain, which seemed like a much better idea than being left alone in the countryside.

The convoy of tanks, trucks, jeeps, artillery pieces, and personnel carriers was several miles long. We slowly wound our way along the coast, through many villages whose occupants were eager to sell us anything from Coca-Cola to dried monkey paws. In the evenings, we camped, with the nearby infantry shooting flare shells from mortars all night. I was still unsure why, but it certainly kept us awake.

We soon entered the steep and isolated passes of the central highland’s mountains, in which we came across the smoky villages of the Montagnard people, hill dwellers who lived in grass huts built on stilts. After several days, we arrived at Dragon Mountain, where the division was already in the early stages of Operation Junction City, a huge corps-sized effort to defeat the enemy in the central highlands.

It turned out, however, that I had made the wrong decision, and everyone back in Nha Trang was furious at me for going with the 4th Division. They had at last answered my twix queries by telling me to continue psyching out the communists from the Military Assistance Command-Vietnam (MACV) compound near Tuy Hoa—but by then the brigade signal section was packed up and convoying up the road with the rest of us, so I never got the message.

I returned to Tuy Hoa on a UH-1 Huey helicopter gunship and set up operations at MACV. It was an entirely different experience from being with the infantry. MACV had ice cream and hot food, and at night showed movies at an outdoor theater. I had my own room, with a bed, bathroom, and shower. Sometime during this period, I was promoted to first lieutenant, a distinction that signified I was no longer a complete and utter shavetail.

But what we were doing was still serious business, and I was soon reminded that the war was always with us. The compound was surrounded by a stone wall about six feet high, and one night somebody left his steel helmet on top of it. Right about sundown, the helmet suddenly flew into the air. Upon investigation, it was found to have a bullet hole clean through it. Since it was ruined, the next night someone placed it back atop the wall, and about the same time several of the men swore they heard a bullet pass through the air. Two nights later, the helmet flew off the wall again; the sniper had a clean shot. He also had an almost foolproof MO: he fired only a single shot; it was always right before dark. We knew he had to be somewhere in the line of trees across the rice paddy, but several villages with hundreds of people lived there. MACV sent out teams to get him, but he was never caught, and after a while the helmet looked like a piece of Swiss cheese.

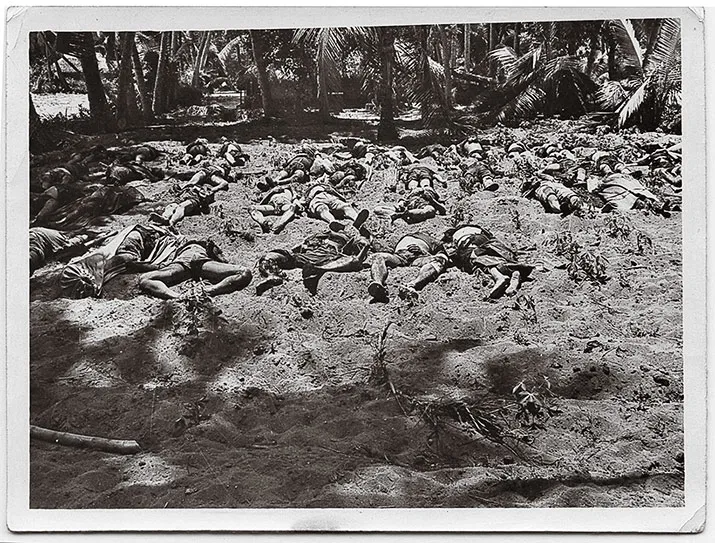

One day I was summoned by the MACV commander and told to provide psychological operations assistance to an infantry regiment from South Korea that was operating north of Tuy Hoa. In particular, I was told that the colonel commanding the regiment wished for me to be his guest for a luncheon that very day. I put on a clean uniform and had my driver take me to the South Koreans’ headquarters; there, I was told that the luncheon was to be in the field where their troops recently had an encounter with the NVA.

While I was with the regiment, a Major Pak was to be my guide and interpreter. He had been educated “in your country, at UCLA.” Some distance from our destination, we began to see the results of the Koreans’ encounter. Bodies started to appear near the road and in the paddy fields. It must have been a running engagement, and the South Koreans hadn’t even collected enemy gear and removed their dead and wounded.

When I arrived at the colonel’s temporary headquarters, it became apparent that the luncheon would be al fresco: A long table had been set in a stucco building, the roof of which had been blown off. Across a field, dozens of bodies stretched into the distance. The Korean colonel was full of good cheer, partly because the battle had been successful and partly because he looked forward to a respectable meal. He seemed particularly proud that he could offer me a bottle of Coca-Cola—over ice!

The meal began appropriately enough with soup, served by stiff Korean privates who had clearly been told that if they knew what was good for them, they would be excellent waiters. At one point, I spooned up some broth that was filled with little grayish-white things like limp grains of rice, and asked Major Pak what they might be. “I believe in English you would call that toad larva,” he replied with a nod and a grin. The meal went on in that vein for most of the afternoon. There must have been at least a dozen courses, one of them an excellent roasted pig, which the colonel informed me had become collateral damage from the fighting. Same was true with the next course—duck breast on a wood spit with kimchi, fermented cabbage.

The colonel told us that he was interested in transforming his victory into a propaganda coup against the enemy, at least two battalions of which were lurking across a ridgeline visible from the dining table. He wanted to drop leaflets on them. I said I could have any kind of leaflet he wanted made up and dropped by the Air Force the following morning. Major Pak told me the colonel wanted to send the enemy soldiers a “friendly” message. “He has beaten them, and now they can honorably surrender, and will be well fed and well treated,” said Pak.

I spent the evening designing the leaflet. The colonel even wanted his name on it—“Colonel Moon.” I sent in the request to Nha Trang, asking that they put some “doves of peace” on the leaflet, and perhaps, in consideration of the colonel’s name, a full, beaming moon. I gave them the coordinates I’d taken off a map after the luncheon, and headquarters promised to have 40,000 leaflets and Chieu Hoi passes laid across the area the next day. I never found out if it got the desired results.

***

One of the pilots I’d become especially friendly with was a forward air controller, Air Force Major Mo Cotner, whom the other pilots jovially called the Old Gray Eagle because in his 40s, his hair had turned white. Mo liked flying gliders for sport, and he was going to teach me to fly them when we returned. It never happened. About three months after I left, in 1967, he was killed.

From the first concept, I had never liked the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall—a black gash in the ground with the names of our dead on it; it sounded like we were supposed to be ashamed of the war. But one night about 15 years ago, while in Washington, D.C., my wife and I drove past it, and on impulse I stopped and we walked over to it. The memorial didn’t have a register then, just 58,000 names listed by year and date of death. I stood there in the middle, bewildered, and mumbled something about wanting to find Mo Cotner.

My wife, who is clairvoyant, walked up to one of the panels, put her finger to a name, and turned to me. “Would that be Morrison Cotner?” she asked. Indeed it was. I looked up other names. It was extremely moving, and I had been wrong about the memorial.

The war is long, long, past us now. We are old men, as the veterans of World War I were when we were young and brave. Among other things, I have written a number of military histories, and on one occasion several years ago, I traveled to Nashville, Tennessee, to speak to a large group about a book I had written on World War I. In the audience was the writer Charles Bracelen Flood, also an author of military history, whom I hadn’t seen in nearly 40 years.

Charlie Flood and I had become friends at the MACV compound while he was there researching his excellent book on Vietnam, The War of the Innocents, published in 1969. Charlie was the first real writer I’d ever met. After the speech, he and I went into the bar for some catching up, and toward the end of the conversation he asked, “Say, do you remember that helmet?”

“The one they used to put on the wall and the guy shot at it all the time?”

“The same,” he said, “and I have it. When our bunch was pulling out, I asked around and nobody wanted it, so I brought it home. It has six bullet holes and nine dents in it.”

“Really?”

“Yes,” he said. “I keep it on my desk. When people ask about it, I tell them that’s the helmet I wore in Vietnam!”

Winston Groom is the author of 19 books, including Forrest Gump and the Pulitzer finalist Conversations With the Enemy. His latest book, The Aviators, was released last November 5 by Random House.