Control the Air

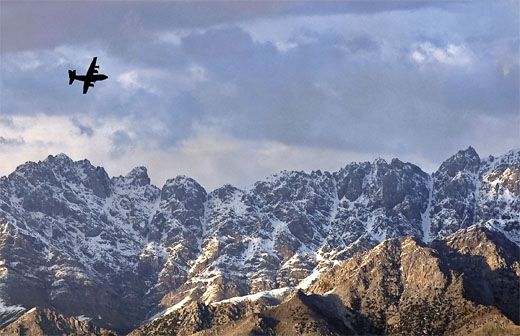

On the ground with Marines in Afghanistan, the author sees a different side of close air support.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/closeair-flash.jpg)

A familiar voice greets me from the shadows of an earthen barrier in Watapor Village, a few miles west of Pakistan in Afghanistan’s mountainous Kunar Province. “What brings you out to this neck of the woods?” asks Marine Captain Zach Rashman. Fresh off the back of a troop transport, I join Rashman behind the barrier to escape the sun as we await a nighttime convoy. We’re headed to Camp Blessing, a military base about the size of a small city park; the Marines call it “The Edge of the Empire.” From this outpost, a platoon from the Second Battalion, Third Marine Regiment has been trying to ensure stability in the area by befriending villagers and flushing out enemy militias. Some of their adversaries may have fought for the Taliban, others for al Qaeda; others are on their own. U.S. intelligence officers have identified 22 different groups of bad guys in the province.

Now in October 2005, the platoon is preparing for Operation Valdez, named in honor of Lance Corporal Steven Valdez, a Marine killed at the base by a mortar lobbed from a nearby ridge. The purpose of the mission is to locate the spot from which that mortar was launched and record its coordinates in order to rapidly return fire should the position be used for another attack.

I had met Rashman six months ago, and 8,000 miles away, when he was a first lieutenant and 15 pounds heavier. At a live-fire training area outside Twentynine Palms, California, I watched him rehearse the job he’s here to do as a forward air controller: guide weapons from aircraft to the precise spot where ground forces need them. In answer to his question, I came to Afghanistan, embedded with the Second Battalion, to observe how the often misunderstood mission of close air support is conducted. Having seen how Marines train for it, I’ll be able to see if the training matches what is required in combat. Rashman, a 26-year-old CH-53D helicopter pilot who had just recently volunteered for a tour to work side by side with infantry, is able to point out almost immediately one big difference. “What you saw at Twentynine Palms six months ago was all USMC,” he says, “Marine Air, Marine infantry, Marine artillery—Marine everything. It’s all joint here. Local Afghan forces roll with Marine grunts. We get lifted by Army Chinooks. Air Force A-10s provide fixed wing. Higher [command] even pushes us special operations AC-130s every now and again, and there is usually a Predator buzzing around somewhere.”

A day after my arrival, I’m accompanying the platoon as they deploy from the base to destroy cave complexes near the mortar position where the enemy could hide. This will be my first combat experience involving CAS—pronounced “cass” in military circles—and I tap my fingers nervously on the ceramic plates of my body armor. As the order to move to the landing zone is given, I see Rashman running for a combat operations center instead of the waiting helicopters.

“Aren’t you coming?” I ask.

“I’m stayin’ in the rear for this one,” he says.

“We got air, don’t we?” I practically cry, and I flash back on a prediction Rashman made a day or two prior: that in combat I would understand the urgency of wanting every form of supporting fire available. I understand already, and I haven’t even left the base.

“Type-3 control, brother,” he responds, indicating that he, as a controller, will grant aircraft permission to engage on their own as long as the strike fits a series of parameters, including where and when they plan to drop ordnance. “I have to stay behind to act as not only the forward air controller, but to deconflict [separate airplanes from one another and from munitions] and deal with other types of air in addition to CAS, all that good stuff…. You’ll be fine, just keep your head down.”

I hurry to catch the 20 Marines quietly marching away and reach the helicopter landing zone just as two Army CH-47 Chinooks, accompanied by two Army AH-64 Apache gunships, appear in the distance. My minder, First Lieutenant Patrick Kinser, explains the plan to me as Camp Blessing’s mortar crews launch a barrage of 120-mm rounds at a ridge protruding high above the firebase. Textbook close air support missions start this way—“suppression of enemy air defenses,” the military calls it—to keep the aircraft called in for an attack from being attacked themselves.

“The birds’ll lift us and we’ll head down valley, as if we’re on a routine flight, but then we’ll bank hard and come in for a surprise attack,” he continues. “Apaches will fly cover for us, then do close air support, if necessary.”

Sensing my anxiety, the 24-year-old lieutenant adds, “A-10s are rippin’ up here right now for CAS work, Rashman’s already got ’em cleared. Hope you get to see some gun runs. You haven’t lived till you’ve seen an A-10 hit a position with that 30-mm rotary gun. And tighten your helmet. Looks loose.”

The Chinooks roar onto the dirt landing strip as the Apaches carve broad arcs overhead, keeping watch for enemy movement. Twenty Marines and 20 local Afghan Security Forces personnel load a week’s worth of food and bottled water, then themselves, into the big helicopters. The engines spin up, and we lift away from the firebase.

Like Clockwork

Almost every Marine headed to Afghanistan or Iraq stops first at Twentynine Palms, the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in California’s Mojave Desert, for roughly 30 days of combat training. Six months before Operation Valdez, I’m there too, crouching next to Zach Rashman as he eyes a target a half-mile distant, near the bottom of a gently sloping desert bowl. The Second Battalion, Third Marine regiment, based out of Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, is in the second week of a pre-deployment workup. Under the intense supervision of “Coyotes,” a select group who teach, oversee, and maintain the safety of visiting exercise forces, the battalion is preparing to assault a target—a cluster of dilapidated tank hulks—in a live-fire training exercise. As a forward air controller, Rashman is one of three Marines who will be directing the fire.

A Marine battalion can call on mortars, artillery, and aircraft, and each of the three kinds of fire is typically provided by operators who cannot see their targets. Instead, forward observers act as eyes for the weapons operators. Observers for each of the three forms make up the battalion’s fire support team, or FiST, and coordinate their respective “fires” for the maximum destructive power and psychological impact.

Rashman and the other members of the FiST mark their maps and check and re-check their radios in preparation for the fury they will soon be directing onto the targets.

“This is a combined, simultaneous live-fire event; we design the training to be as close to the real thing as possible,” says Lieutenant Colonel Doug Pasnik, my guide for the day. Pasnik, an F/A-18D naval flight officer and a veteran of dozens of recent close air support missions in Iraq, runs the air support component of the day’s exercise.

On the rocky knoll where the fire support team works, we hear the first rumbling booms of distant artillery pieces; 155-mm shells thunder into the target area seconds later, sending plumes of earth into the sky. UH-1 Huey and AH-1 Cobra gunships crest a distant ridge and assume a holding pattern, awaiting targeting instructions from Rashman. Coordinates blare from Coyotes’ radios and members of the FiST shout back and forth, sometimes peering through binoculars, sometimes noting positions on the backs of their hands.

“Rashman will be doing Type 1 control, meaning he sees both the target and the attacking aircraft,” Pasnik says, holding a radio set in each hand. Type 2 control means the ground controller is able to see either the target or the aircraft, or neither, if he has an observer who can see the target. Type 3 is similar to Type 2, except that the controller doesn’t clear a strike for each release; instead, he clears the aircraft to engage for a period of time and within a limited area.

“Got ’em—eyes on the Hornets!” shouts a member of the FiST as he thrusts his index finger high into the air. Two F/A-18C Hornets streak across the powder blue sky. Smoke 21, the lead Hornet pilot, checks in with Rashman.

“One of the most difficult—and important—aspects of controlling air is deconflicting with other aircraft and fires,” Pasnik explains as the Hornets disappear into the distance. “You have to ensure that your aircraft won’t be in danger of getting hit by an artillery or mortar shell—or another jet or helicopter.”

Infantry, packed into swift-moving armored personnel carriers, push into my field of view as artillery-lobbed “white star cluster” rounds burst over the target, showering it with burning phosphorus and marking it for the air strikes to come.

“Okay,” Pasnik updates me, “Rashman’s worked the Hornets into the fire support plan; the pilots have told him how long they’ll be on station and what they’re carrying. He’s deconflicted the other fires; they’ll be shutting down just before the jets are inbound. He’s holding the two gunships off laterally, for employment later.”

As Pasnik refocuses his attention on one of his radios, pieces of this seemingly chaotic puzzle click together for me. In order to transmit all relevant information to an attacking aircraft, ground controllers use a standardized set of instructions, the “Nine-Line Brief.” The brief details the nine points of information required by pilots tasked with close air support, including target descriptions and locations of enemies and friendlies. Once an aviator reads the information back, the ground controller will issue the “cleared hot” call, granting permission to release ordnance.

Just as Rashman completes his brief, Smoke 21 rolls in; the pilot immediately confirms the information. Rashman’s voice booms out of the Coyotes’ monitoring radios: “Cleared hot.”

Smoke 21 dives and the roar of twin jet engines reverberates in my chest. A hundred-yard wall of roiling fire vaults skyward as six 500-pound, Mk82 bombs slam into the ground. Smoke 21 banks hard away from the conflagration—and barrel rolls. The FiST erupts in cheers. The rattle of .50-caliber machine gun fire resonates from tanks that have taken positions in the hills around the target, 81-mm mortars begin slamming the target anew, and the infantry swarms over its goal.

“That,” Pasnik says, “is how CAS is done.”

The Chaos of Anaconda

By all accounts, one of the great successes of the war in Afghanistan was an unprecedented coordination of air power with special operations forces on the ground, who accompanied Northern Alliance fighters and designated enemy targets for air strikes. But when the military leaders of the Afghanistan campaigns attempted to combine special operations with conventional forces for large, coordinated missions, there were also failures.

Among the most visible breakdowns—and the most analyzed—was the confusion that jeopardized Operation Anaconda in March 2002. Planned to trap al Qaeda and Taliban fighters who had slipped away from the December 2001 battles in Tora Bora and who were hiding in eastern Afghanistan, Operation Anaconda was a weeks-long battle in mountainous terrain. It had been planned months earlier and always with the expectation of close air support, but no notification had been given to air commanders until five days before the battle began, and no system was in place to manage and integrate close air support requests.

The night before the battle began, Air Force Major Scott “Muck” Campbell and Lieutenant Colonel Eddie “K9” Kostelnik had been called out of their base in Kuwait and were the first A-10 Thunderbolt II pilots on the scene in the Shahi Kot Valley.

“Nobody knew where anybody was,” says Campbell. “Nobody was deconflicting. The biggest threat was us running into each other, not the bad guys shooting at us.” Campbell describes pulling off of a gun run only to find himself just a few hundred yards off the nose of an AC-130. At one point, a Navy F/A-18 rocketed between his wingman’s aircraft and his own. “K9 and I were getting ‘talked on’ to a target and a JDAM [Joint Direct Attack Munition] goes off directly below us, and we’re like ‘Where’d that come from?’ It was completely out of control,” says Campbell. “A mortar would impact and we’d literally have a crowd [of friendly ground troops] calling in.”

It wasn’t that the air controllers and pilots weren’t speaking the same language. The military has made certain that training in every service is based on the same set of protocols. “The air controller course I went through is virtually identical to those of other branches,” says Rashman. “Upon graduation we’re all Joint Terminal Attack Controllers—JTACs.”

The problem in Anaconda came from the mission’s planning staff. In a study of joint operations conducted for the Naval War College, Marine Colonel Norman Cooling blames the disarray during the battle on the failure to integrate command. Special operations forces in the area reported to U.S. Central Command instead of to Army Major General Franklin Hagenback, the joint task force commander to whom all other participants in the battle reported. “Failures in integrated planning and intelligence sharing produced highly publicized fratricide incidents and situations such as that on ‘Roberts’ Ridge’ where a Ranger Quick Reaction Force inserted into a known enemy kill zone,” Cooling wrote. (In the Roberts’ Ridge incident, Navy Petty Officer First Class Neil Roberts was killed by enemy gunfire. Six more Americans died trying to rescue him.)

Military leaders analyzed the deficiencies in integrating air power with ground forces and proposed twin corrections: First, insist on unity of command. In Afghanistan, two different commands, one controlling special forces, the other controlling conventional forces, had produced an us-and-them culture, similar to the division that had characterized the Army and Air Force approaches to air power since the services separated in 1947 (see “A Little Help From Above,” p. 56). Second, make close air support a part of the original battle plan instead of an emergency call. “We need to quit using CAS to save lives and start using it to win battles,” says Colonel John Allison, former chief of the close attack branch in the Air Force joint air-ground division, tasked with integrating ground and air operations. “We have grown an entire generation of Army officers who think there will always be airplanes overhead. It is an airpower buffet, hot and ready 24/7. You get hungry and go eat—no planning required. The Air Force is quite good at doing close air support…but if the Army doesn’t incorporate air into its maneuver and fire plans from the beginning, it will always be the 911 call.”

Combat CAS

On Operation Valdez, the mission runs as smoothly as the training I witnessed at Twentynine Palms. The two Chinooks land side by side and lower their loading ramps on a flat, grassy section of the target ridge. Motivated by a stiff tug by Corporal Justin Bradley, a 6-foot-5, 270-pound squad leader, I bolt down the loading ramp and immediately gaze skyward to see one of the most soothing views of my life—Apaches roving the airspace high above nearby ridgelines and A-10s soaring above them.

“Show-of-force CAS!” Bradley yells over the shriek of the Chinooks’ engines. “Just the sound of those A-10s keeps the bad guys down. Everybody says the A-10s are ugly. Betcha never seen such a beautiful sight in your life though.”

They are a reassuring sight, but I don’t gaze upward long. I’m busy finding a rock to take cover behind.

Apaches, A-10s, and even an AC-130 gunship (at night) fly support missions throughout the next four days—never firing, but remaining on station and ready to provide support at a moment’s notice as the Marines run patrols, looking for the mortar position. The roar of the Warthogs and the whine of lower flying Apaches echo through the steep valleys of the Hindu Kush. Throughout the operation, our interpreters and attached Afghan fighters pick up Taliban radio chatter and alert us of impending ambushes. But none comes. During a day patrol led by Bradley, the Marines on his squad discover signs of a mortar position and note its coordinates, then blow up a small cave complex where they determined the enemy had hidden munitions. That done, we hike back to Camp Blessing.

Weeks later, out on another operation, I discover that the Marines can’t always count on air support. As we ground-pound up and down the steep Afghan hills on Operation Pil (“elephant” in the Afghan language Dari), the air above us is empty. Now, machine gun rounds zip over my head, splintering tree branches and pinging boulders at the patrol base, coming within inches of people in our group. Lieutenant Kinser directs the Marines to return fire at a ridge above us where he detected muzzle flashes. The grunts squeeze off bursts from M240G light machine guns, M16s, and M249s. The ambush quiets. We maintain our covered position, waiting for air to arrive.

Later that night some members of our attached scout sniper team reflect on the firefight. “No air on station. Safe for them to pop up and hit us,” team leader Sergeant Keith Eggers surmises.

No one understands why aircraft haven’t been sent to hit the ridge from where we were ambushed; nothing shows up for hours, long after the shooters have fled. We later learn that Rashman had immediately requested support, but an inbound C-130 with landing gear problems shut down the field at Bagram Air Base, grounding the A-10s.

Rashman is on the mission with us this time, and he seems always to be working his radios. Since the battalion has only two forward air controllers to support operations spread across hundreds of square miles, Rashman is called upon to clear air on targets he often not only can’t see, but isn’t even near—at all hours of the day and night. But he says that the chance to fight alongside infantry is why he chose to temporarily leave his career flying helicopters. “Ask any [Marine] aviator who has done a tour as a forward air controller what their favorite billet has been, and they’ll tell you the FAC tour,” he maintains.

In 2003, Marines got their first glimpse of a system that can receive images from aircraft, including unmanned aerial vehicles, and relay instructions using the system’s radio link. Designed originally for the Air Force and called Rover (for Remote Optical Video Enhanced Receiver), the system enables ground forces to see what pilots see through their targeting pods. Now real-time imagery can be fed across the battlefield to commanders, pilots, air controllers, and ground troops. That ability is considered vital when attacking fleeting targets or supporting friendly troops on the move across long distances. Future wars, like current ones, will no doubt require that kind of attack and that kind of support.

A Little Help From Above

Although the first close air support sorties were flown in the Italo-Turkish war of 1911-1912, World War I began without a formal doctrine for using aircraft to support troops on the ground. That was remedied by France in April 1916, when it became the first country to codify the mission.

The most famous U.S. display of the mission’s effectiveness was made in the summer of 1944, when General George Patton’s Third Army raced toward Germany through France. As Patton’s tanks advanced, the P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts of the XIX Tactical Air Command, led by General O.P. Weyland Jr., flew in front of them and struck opposing tanks, blew up tank barriers, and strafed troops, trucks, and gun emplacements. Control of the pilots in the air came not from trained infantry on the ground, but from P-51 and P-47 pilots stationed at the head of the advancing tank columns. The position of air liaison officer, as Weyland called the pilot directing the air strikes, was a coveted one: Pilots took pride in helping their airborne brethren get weapons squarely on the target. The speed of Weyland’s air strikes overcame an Army belief that aircraft should be used only when artillery couldn’t reach.

In that campaign, the performance of the Republic P-47D Thunderbolt, with eight .50-caliber machine guns and the capacity for 2,500 pounds of bombs, reinforced the idea (introduced by a German aircraft in World War I, the Halberstadt CL II) that an aircraft could be designed and produced specifically for close air support. The Jug, as its pilots called it, could also survive severe damage from ground fire to get its pilots home.

The years following World War II were fraught with disagreement among the U.S. military branches over CAS, particularly between the Army and the newly formed Air Force. With responsibilities for all types of air missions — strategic bombing, interdiction (damaging the enemy’s military potential before it can be brought to bear), and transport, as well as close air support — the Air Force began to concentrate its resources on striking the enemy from afar. The Army argued that it needed more control over U.S. Air Force aircraft to help its infantry maneuver because there were still ground wars to fight.

The services disagreed more fervently over priorities for air power at the outbreak of the Korean War than at any other time. The decision in Korea to place Marine Corps air operations under the command of the Air Force exacerbated the discord, but the war also produced another storied demonstration of close air support. As the First Marine Division withdrew fighting from the Chosin Reservoir in the winter of 1950, Marine F4U Corsairs flew day and night, using napalm, gun runs, and rocket attacks to keep the Chinese army hunkered down.

Long into the cold war, the strategic nuclear mission remained the Department of Defense’s air priority. But experience on the ground in the Vietnam War, which began without a joint Army-Air Force doctrine of close air support, ushered in new ideas and capabilities for CAS. Two Marine Corps aviators proposed a dedicated forward air controller aircraft, which became the OV-10 Bronco, used by all services. An Air Force captain pushed the development of the side-firing gunship (initially developed for camp perimeter defense, this platform would evolve into one of the deadliest CAS platforms available). The gunship became the AC-130, flown today by special operations crews. And new policies allowed commanders in all services to plan and coordinate air operations with other military branches.

After the strategic air power successes of Operation Desert Storm, debates over the priorities of air missions have continued. The challenge for the air services now is how best to use air power in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, where typically the enemy forces are not concentrated but dispersed and sometimes impossible to find.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ED_DARACK.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ED_DARACK.jpg)