Kunming Remembers the Flying Tigers

A photography exhibit based on the work of R.T. Smith honors the legendary fighter group that saved a Chinese city.

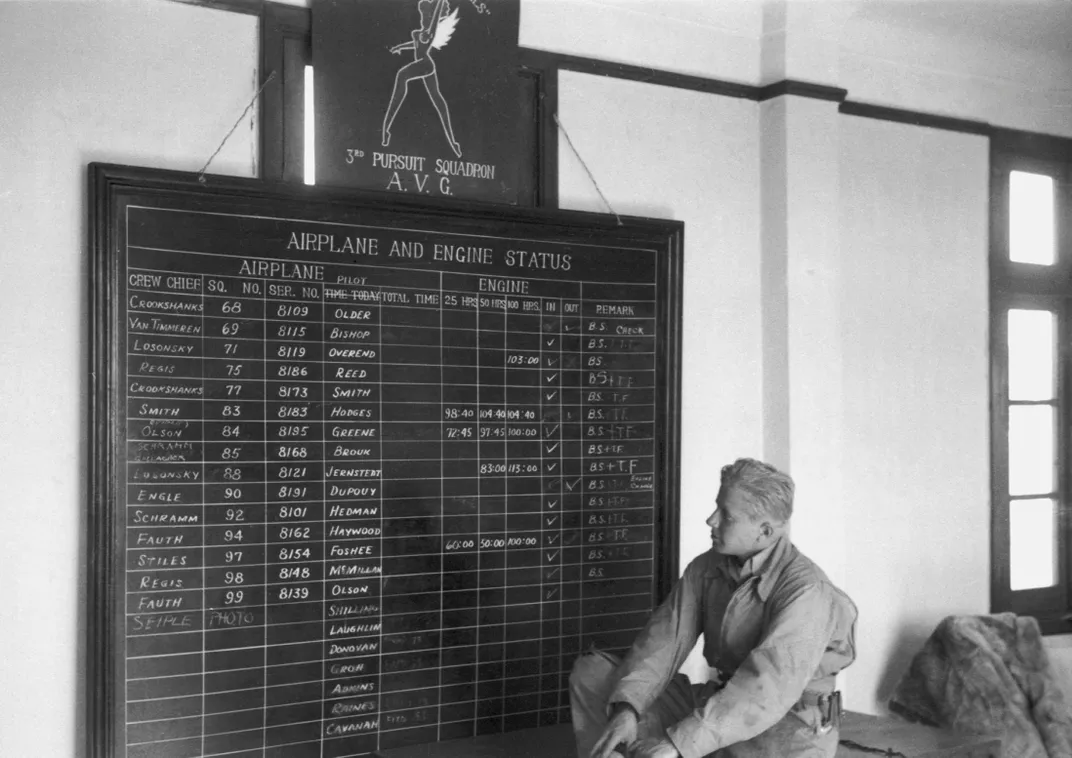

This December, the city of Kunming, a metropolis of 4.6 million in southwest China, is celebrating a group of Americans who 75 years ago saved the city from devastation. The First American Volunteer Group, better known as the Flying Tigers, was a short-lived unit, but during the seven months they flew combat, under the leadership of Claire Lee Chennault, they destroyed almost 300 Japanese attacking airplanes. To honor the group, the Kunming City Museum is mounting an exhibit of photographs taken by one of the pilots: R.T. Smith, a fighter ace, photographer, and author of the 1986 memoir Tale of a Tiger. His photographs show the shark-faced Curtiss P-40s that the group became famous for, as well as scenes of their life on the base in Kunming. What they don’t show is the desperation of a city that lay within easy reach of Japanese warplanes or the furious air battles that saved it.

By December 1941, the city of Kunming had suffered attacks by Japanese bombers for almost three years. The punishing raids were part of an assault on China that the Roosevelt administration interpreted as a threat to American interests in the region. The president, bound by the 1939 Neutrality act, responded with a covert operation. Months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor pulled the United States into war, a group of almost 100 pilots recruited from the U.S. Army Air Corps, Navy, and Marines resigned from their services and volunteered to defend China against Japan. In the summer of 1941, the First American Volunteer Group started training at a remote British airfield in Burma.

On the day the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, the Japanese army landed troops in Thailand, Malaya, and the Philippines. Days later, on December 18, AVG commander Claire Chennault, a retired U.S. Army Air Corps pilot who had become an adviser to the Chinese air force, dispatched two squadrons to Kunming, which became the group’s permanent base. Japanese bombers had hit Kunming that morning, and some 400 Chinese had been killed. When the American Volunteer Group landed, the city was still smoldering.

Two days later, on the morning of December 20, the Japanese bombers came again. A network of Chinese observers, which Chennault had established in distant villages, reported 10 Kawasaki Ki-48 bombers heading toward the city. Eight AVG pilots took off and stayed close to the base. When the Japanese pilots spotted them, the attackers jettisoned their bombs and fled south, where 14 additional AVG fighters patrolled. The air discipline Chennault had drilled into the young pilots was quickly forgotten as the encounter turned into a free-for-all. Three Japanese bombers went down in flames. The heavily damaged survivors fled back to base in Indochina. By some accounts only one made it back.

The AVG had become the heroes of Kunming. In publicizing the news of the battle, Time magazine hailed the American pilots as “Flying Tigers.” The nickname stemmed from the flying tiger emblem that Walt Disney Studios had created for the volunteer airmen two months earlier, and it is how they have been known ever since the Time report.

On the evening of December 20, the American pilots were feted at a banquet, an expression of gratitude from the people of Kunming. Eleven days later, the provincial governor decorated the pilots who had engaged in the fight. It was an astonishing defeat for the Japanese air force and, as it turned out, a lasting reprieve for Kunming. In his memoir Way of a Fighter, Chennault wrote: “Japanese airmen never again tried to bomb Kunming while the AVG defended it. For many months afterwards, they sniffed about the edges of the warning net, but never ventured near Kunming.”

Kunming has never forgotten, and I expect the exhibition of photographs at the city museum this month to be very well attended. Some years ago on the outskirts of Kunming, I attended the unveiling of a large bronze statue honoring the Flying Tigers. The taxi driver taking me back to the city got a look at the statue and was curious. “Fei Hu [Flying Tigers],” I said. Ah, the Americans. His grandfather had told him the stories. It had been a long ride, but the driver refused to let me pay. “I cannot take your money,” he said. “You are a friend of the Flying Tigers. We remember them.”