Letters From a WWI Jenny Pilot

In 1918, my grandfather’s wish was simple: “Give me a Lewis gun in the cockpit of a fast fighter plane, and I know that I’d be satisfied with life.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/7e/977eee8d-73dd-4f50-9a59-e9ef814cfd2f/01_my-grandpa-in-wwi_feb_14.jpg)

When the United States enters the first world war, in the spring of 1917, Louis Crawford is 33 years old, has two children, and works as a county school superintendant in rural North Carolina. He has been a railroad draftsman in the Arizona Territory, a journalist in Philadelphia, and a moderately successful author of popular short fiction. But it’s his earlier experience—as a cavalry sergeant in the war in the Philippines and as an infantry officer during the Mexican revolution—that commends him to the U.S. Army. His application is accepted, and he is shipped off to Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, to train as a company commander destined for the trenches. Among his cadre at the post is Captain Dwight David Eisenhower. Among his classmates: First Lieutenant F. Scott Fitzgerald. And among his dreams is one that has been with him since childhood: the hope of emulating the valor of his father, a thrice-wounded Union veteran of the Civil War.

“My first childhood memory is of my father’s saber hanging on the wall,” Louis writes his wife Kate. “Can you imagine what that means to a boy who wants to be a soldier?”

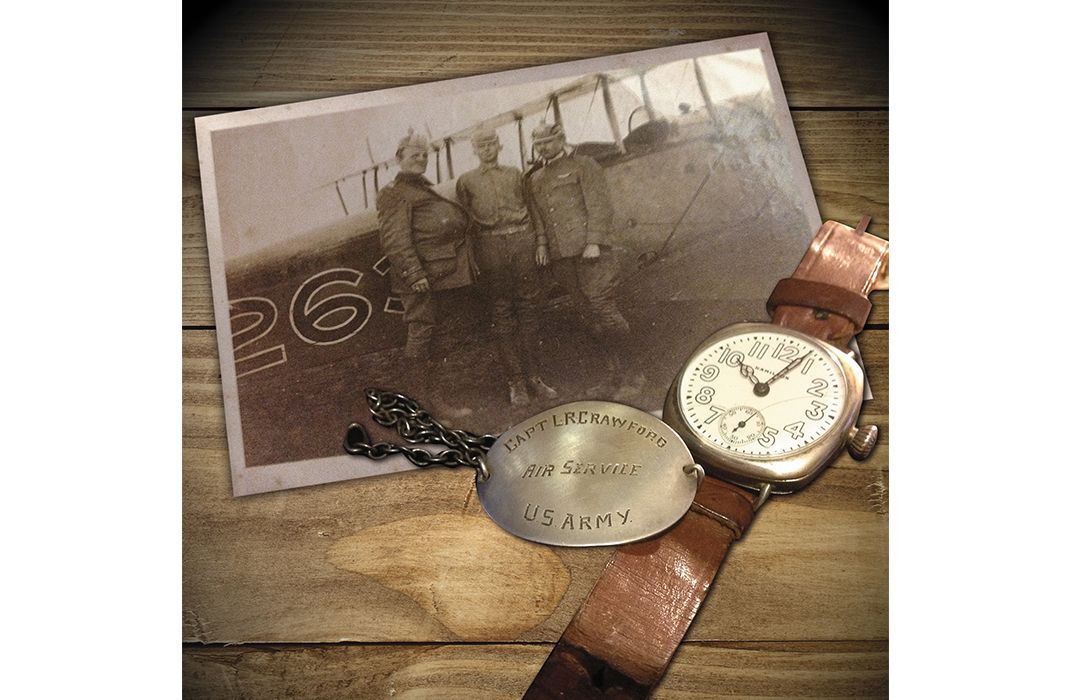

Louis Crawford is my grandfather, and I inherited his mementos from World War I. From his letters, his journal, and his photographs, I have been able to put together a picture of a man who, because of his patriotism and the outbreak of war, unexpectedly came to fall in love with flying.

Louis trains hard at Oglethorpe, but an X-ray taken during a routine physical detects a shadow on his lung: tuberculosis. The findings deny him a combat posting. In his diary, he records his “bitter disappointment.”

But he will not give up his dream of active service. He travels to the War Department in Washington, D.C., and comes away with a commission as a first lieutenant in the Signal Corps’ newly formed aviation wing. “I was to be known as a Ground Officer,” he writes in his diary. “I had never even thought of entering the Air Service before.”

On November 26, 1917, Lieutenant Crawford reports for duty as officer in charge of maintenance at Kelly Field, near San Antonio, Texas. The base would train most of the U.S. fighter pilots who served in France, as well as many of the mechanics who supported their flying.

My grandfather’s work swiftly grows to include responsibilities as salvage officer, officer in charge of summary courts, and finally commander of the field’s troop of carrier pigeons, birds with tiny tin cups under their wings who serve as the only means pilots aloft have of contacting their base.

In May 1918, he is promoted to captain, but he frets that his work is merely routine. I can easily envision the new captain—after months of salvage and maintenance work, staffing courts-martial, and tending to birds—standing one day at the edge of the field. He closely watches the fragile biplanes trudge down the rutted runway with their sagging wings and shaking fabric before suddenly falconing into the sky; later that evening he writes in his diary, “I realized for the first time that it could be done.”

He gets his chance. In August 1918, the army opens flight training to the ground officers. Captain Crawford applies at once.

He is not a natural pilot. His journal and his letters home document his struggles to master a skill so foreign to anything he had ever experienced before. His competence grows, and his fearlessness is never in question. Once he notes, “I find that I do not ever think of the personal danger while flying, my chief idea being not to smash up the ship.” One of his instructors remarks, “Captain Crawford seems to disregard the ground.”

He flies the Curtiss JN-4, a homely little biplane nicknamed the Jenny. The JN-4 can reach a maximum speed of 75 mph and climb to a service ceiling of 6,500 feet—impressive figures for its day. The airplane’s primary use is as a trainer, and virtually every American and Canadian pilot sent to the front will have spent time in the Jenny’s dual cockpits.

My grandfather painstakingly masters the demanding ship, and comes to love it. His hours in the Jenny prompt the most exact writing to be found in his letters, most of them written to his wife. It is as though he were replaying every moment of one flight in order to correct its faults in the next. And he’s very critical, indicting himself not only for technical flaws but also for matters of style: “Banked for the turn too close to the ground. No harm done, but bad form.” His instructors say little, which causes anxiety, but they move him along in increasingly demanding tasks. Within a week of his first flight, his teacher will casually kick a plane into a spin at 2,500 feet and wait for Louis to find his way out of it.

I did pretty well, but I learned the danger of it, for on one trial I could not centralize my rudder soon enough and we got to revolving very rapidly and fell 1000 ft. before I could level the ship. On another one I tried to level before the spin had developed and actually kicked the ship over on its back. This had me guessing for some time before we described a half loop to come out.

“It’s a lot of fun,” he insists, then adds honestly, “when your instructor is along to give you nerve.”

One of Louis’ instructors, a Lieutenant Merrill, assigns the fledgling pilot a series of stunts designed to increase his confidence. In the first, a power spiral, a steep bank throws the Jenny on its side, shifting the rudder and elevator positions. “It’s hard to remember the change,” Louis writes, “but if you make an error in your controls you are very apt to go into a spin. I cut several of these spirals, but found them difficult.”

He masters the maneuver and soldiers on, though each day presents its challenges.

I had a thriller in the air today—bumps like never before—with all controls held neutral, the ship would roll and toss just like a small boat in a high sea. You had to keep fighting it all the time to stay right side up. I have never worked so hard as I did. The air pockets were fierce. It’s a queer sensation to fall fifty feet or shoot straight up, to feel the bottom of the ship drop out from under you…

And there is at least one moment of manifest danger when a new instructor, Lieutenant Funck, twists the airplane into an Immelmann, and a stream of oil flies back across the fuselage and into both cockpits. “It completely blotted out the windshield and my goggles,” he writes. “I pulled them off and got a faceful of oil. The ship, in the meantime, had dropped out of the loop and was volplaning [gliding without power] down…. The strain of the loop in the high wind had broken a feed pipe in the motor. If it had happened to me alone, I think I would have lost control before I discovered the trouble, because I was blinded for several seconds.”

Other barriers stand between Louis and his coveted gold wings. He flies no more than an hour or two a day; he is expected to keep up with many of his regular duties; and his health continues to be fragile. But the greatest threat to his ambition was time. On October 30, he tells his diary, “I now have my back to the wall. The time allotted for dual instruction has expired. I must solo tomorrow.”

On the journal’s next tattered page, he begins to describe this elemental rite. It’s frustrating to be denied the details: Silverfish have eaten almost all of the paper. But at the bottom, a single word—“Celebrate!”—survives.

On June 17, 1918, he promises Kate, “I’m going to have my picture made for you in helmet and goggles,” adding scornfully, “So many here are taken that way of men who never go near a plane.”

Louis is very photogenic: a small, slender man with obsidian eyes, a strong jaw, and a generous mouth. I found another photograph—a comic tableau vivant in which my grandfather stands with two buddies beside a parked JN-4, his belly bloated with a pillow, portraying a fat Prussian foe, a tiny German helmet propped atop his head. Other casual poses find him lounging with brother officers outside his quarters, standing proudly beside the plane cleverly named for his wife (“K-8”), or grinning cheerfully with the post baseball team he managed.

But in his correspondence, he shows a flair for drama. Usually seeking to calm Kate’s worries, he still writes on one occasion, “Know, darling, that if I crash, I’ll be thinking of you as I come spinning down.” And, having mastered a maneuver called the “falling leaf,” he sketches a Jenny slip-sliding down the margin of one page. “It’s a grand sensation—think of me cutting such a stunt 2000 feet in the air!”

Most of his surviving letters are to his wife, but a few are to others. On January 30, 1919, Louis writes a letter to his daughter Louise—my mother—with a long description of his carrier pigeons. He names one for her: “The other day, Lieutenant Blakely flew 100 miles up country and sent me a message by Louise. He turned her loose at 10 am and the message was on my desk at noon.” He describes how the pigeons are summoned: “When they’re all out flying and we want to call them in, we rattle an old tomato can filled with pebbles and they come straight home.” The bird Louise, he tells his daughter, “after carrying the message to me laid a little egg to celebrate the occasion.”

As a pilot, he is quick to pay special attention to the achievements of the Air Service. “Whenever we shot down a German flyer, our planes flew over next day and dropped flowers on the crash site. And the Germans buried young [Quentin] Roosevelt [Theodore’s son], with full honors after they brought him down. The reason for this fellow feeling is that air combat is single-handed fighting—man to man—and that brings out the best there is in a man.”

In the months after his solo, flying becomes one of his regular duties, and one of his greatest delights. Captain Crawford enjoys a style of aviation largely unavailable today. He rides an open cockpit, guided by a compass and a hand-drawn map, following roads, railroad lines, and riverbeds. The wire, wood, and canvas feel alive to him, as well they might to someone whose prior beast of burden had been a horse.

He becomes a capable aviator, and is made an instructor.

Louis can find comedy in flight. In a feature story in the Hertford, North Carolina Herald, he observes: “My favorite stunting ground is a couple of miles south of San Antonio, selected because there are several good fields available in case of trouble. One borders on the State Insane Asylum. Frequently in coming out of loops or Immelmanns while hanging on my back for a second several thousand feet up with only a thin safety belt between me and the hereafter, I have imagined the inmates on the porch beckoning and saying: ‘Come on down, you qualify.’ ”

But as the war enters its final months, he becomes increasingly frustrated at being left out of combat. In one letter he writes of the enemy: “I’ve read where they are using American uniforms to deceive our troops. Oh, for one crack at them! Give me a Lewis gun in the cockpit of a fast fighter plane and I know that I’d be satisfied with life.”

But the Armistice is signed before he gets the chance to fly in combat. Now Captain Crawford has another anxiety to face. He dreams of a major’s gold leaf, but radical post-Armistice reductions in force sweep the services, including the airmen at Kelly Field. During the war, the base hosts a total of nearly a quarter of a million men; the number now shrinks to 10,000. Though Kelly remains open, Headquarters Southern Command determines Colonel Crawford’s unit to be over strength. Somehow, though, my grandfather manages to keep bars on his shoulders: With a new posting as a lieutenant of cavalry, he takes command of troops stationed in Columbus, New Mexico. His service is interrupted in October 1920, when he is ordered to the Cavalry School at Fort Riley, Kansas.

But the illness that has shadowed him grows more aggressive, and on April 9, 1921, he dies in an army hospital in Denver. He is buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, in Virginia.

His last months in uniform offered modest rewards. “This afternoon I rode Jim for two hours and led Kino for exercise,” he wrote from Fort Riley on November 16, 1920. “I was anxious to take the kick out of him. Kino behaved beautifully and I complimented him so much Jim got jealous.”

I have a photograph of my grandfather leading a stocky little cavalry pony out of a dusty corral, getting ready to saddle up and take his place at the head of his unit. His eyes are shaded by the wide brim of his campaign hat; his smile is confident and clear. Pinned to the horizon above the mountains behind him, a little biplane hangs motionless in midair, a Jenny trudging into its new life as barnstormer or mailplane. Lieutenant Crawford has a new life too, and no doubt he misses flying. But he is happy to be working with horses again.