Mystery on Guadalcanal

In the wreckage of a Wildcat lay clues to what happened in a famous World War II dogfight.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/guadalcanal_631-jan07.jpg)

During the opening hours of the U.S. assault on Guadalcanal, the air battle produced one of the most storied combat engagements of the war. After a ferocious exchange of fire, Japanese ace Saburo Sakai shot down a Wildcat, flown by Lieutenant James J. Southerland II. Southerland bailed out and survived. The wreck of his airplane lay hidden for 56 years. In 1998, it was discovered, right where it had fallen.

The more inhospitable its resting place, the better the chance a wrecked airplane has of remaining untouched by scavengers and curiosity-seekers and the more likely it will still hold secrets for historians. Thousands of such ruins remain throughout what was known as the Pacific theater—on rugged mountaintops in New Guinea, in jungle ravines in the Philippines and the Solomons, scattered across tiny islands and a vast area of ocean floor.

Justin Taylan has been cataloging the location of those aircraft wrecks since 1993, when he toured the Pacific battlefields with his grandfather, a combat photographer in the South Pacific during World War II. A serious 28-year-old, Taylan founded PacificGhosts.com to locate and document the wrecks, about 30 of them in the Solomon Islands. He has visted more than 200.

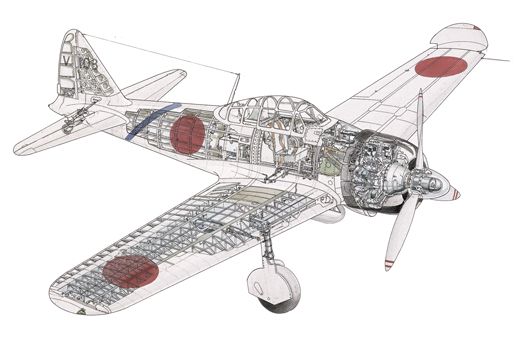

His company maintains a database detailing the research and has produced a CD-ROM on more than 30 of the wrecks (see Reviews & Previews, Apr./May 2003). When I met Taylan, he was publicizing his work at the Planes of Fame Museum at Chino Airport, California; it was the day of an airshow, and a good-size crowd had gathered to look at his photographs and hear him describe his expeditions. We talked about one of his most significant discoveries, the wreck of Southerland’s Grumman F4F Wildcat. It is believed to be the first U.S. Navy aircraft to shoot down an enemy in the Battle of Guadalcanal. It was also one of the first U.S. aircraft shot down in that battle. Both Southerland and Sakai were seriously injured—one stranded behind enemy lines, the other 560 miles from his base—but both lived and later told what happened that day.

Historians know Southerland’s version of the events of August 7, 1942, mainly from his after-action report, which was published in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings in 1943. His aircraft carrier, the USS Saratoga, was one of three tasked with providing air support for the assault on the Solomons and protecting the Navy ships massed off Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The months-long campaign was the first Allied offensive in the Pacific, and it marked the end of Japanese expansion.

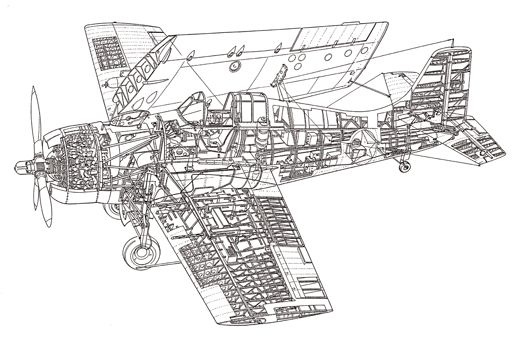

The pilot who shot Southerland down, Petty Officer First Class Saburo Sakai, would become one of Japan’s greatest aces. His version of the dogfight appears in the 1985 book Winged Samurai: Saburo Sakai and the Zero Fighter Pilots (Champlin Fighter Museum Press), written by Henry Sakaida and based on Sakai’s memoirs and on interviews with him. Sakai’s war career became well known with the 1957 autobiography Samurai! (E.P. Dutton and Company), written with aviation historian Martin Caidin. Both Sakaida and Caidin report Sakai’s claim that he could have killed Southerland, but showed mercy by firing at the aircraft’s engine instead of its pilot. In other significant details, the two pilots’ versions match, but both could only surmise why Southerland was unable to fire on Sakai when his Zero slid in front of the F4F (see “The Dogfight,” p. 34). After meeting Taylan, I hoped to examine the wreckage of the Wildcat to find out.

Taylan first saw the crash site in 2003. An islander, Edilon Gii, had come upon it in 1998, and led a group of historians there—among them, Michael Claringbould, who worked with Taylan on the PacificGhosts CD. Last winter, Taylan returned with a documentary film crew from Cineflix Productions in Montreal. Because I had assisted film director Michael Barnes with crash investigations in earlier projects, I was retained to analyze the wreckage of the F4F for the documentary Dogfight Over Guadalcanal, which aired in early November on WGBH’s “NOVA: Secrets of the Dead” series.

On a hot January morning, with cameras and sound gear, we followed Edilon Gii into the jungle. A farmer and hunter (Gii had discovered the wreck in a ravine while hunting wild pig), the 42-year-old guide led us on a clear path for a quarter of a mile, then bushwhacked through ankle-deep marshland. Deep in heavy foliage, Gii pointed his machete at a shattered dish and water can, all that remained of a Japanese field hospital. The air was hot and damp, and the site swarmed with mosquitoes. I could imagine what it must have been like to be a wounded Japanese soldier trying to recuperate at the makeshift infirmary. The Japanese lost 24,600 men—from a force of 30,000—trying to hold on to Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

Southerland walked for three days through this jungle, evading Japanese soldiers, until he reached the coast and sought the help of villagers, including 15-year-old Bruno Nana, who guided Southerland to the Americans. We visited Nana, who still lives on the island, and he talked to us about working for the Japanese during the occupation, laying communication lines. Nana told us that on August 6, 1942, the night before the U.S. invasion, “a German working with the Japanese warned us that the Americans were coming. So I left for my village.” At dawn, the villagers saw ships in the sound and evacuated to higher ground. “We watched the landings and planes coming in,” Nana said. “Boom, boom! We saw the whole thing from the hills.”

Following Gii as he hacked his way through saw grass, we began working our way up some 500 feet to the rim of an ancient volcano. The ridge formed an almost complete circle but opened on the side facing the sea.

“This ridge,” Taylan said, “is the one Sakai mentions in his account.” He pointed at an island to the northeast. “The dogfight began over Tulagi, and descended lower and lower in this direction.” After delivering the fatal blow to Southerland’s Wildcat, Taylan said, “Sakai almost hit this ridge during his pullout.”

I asked where the Wildcat wreckage was from our position, and Gii pointed into the crater.

Bushwhacking through sharp grass, we slipped and skidded down the incline. At one point, we began a traverse down a sheer dropoff, with the heavily laden cameraman showering me with loose rocks, mud, and branches from above and behind. No footholds would support full weight. With a bare hand, I clawed muck from around a vine root and gripped it, and with the other hand grasped a dangling vine. Its thorns cut my hand like razor wire. Working my way from hand-hold to hand-hold, I tried not to think about how we were to eventually get back out.

After about 20 minutes of snail-pace descent, we reached firmer though still steep terrain, and from there eventually reached the bottom of the crater. There, at a twist in a stream, we found the first piece of wreckage, a bullet-riddled aircraft engine bathed in shafts of sunlight.

Thunder echoed off the crater walls, and it began to rain. Swatting mosquitoes, I contemplated the danger of a flash flood and scanned the crater above our location. I saw a deep slash mark about 100 feet up the side of an immense hardwood tree. The scar looked like one that might be made by a spinning propeller. Just beneath it jutted aged splinters where a hefty branch had been broken off. The airplane had likely struck the tree at low velocity, probably in a spin. Had the Wildcat been flying when it hit, the debris pattern would have been in the shape of a triangle, wreckage fanning outward from the point of impact. But the engine poked from the stream bed within yards of the impact scar, and aircraft debris was scattered in all directions. We also realized that storms and floods had surely redistributed the wreckage since crash day.

I studied the engine. One propeller blade was still attached to the prop housing. Bent back at the tip, the blade showed signs that the engine was still pulling power at impact. Side by side near the tip were two bullet holes. One most surely was from a 7.7-mm round, the type fired by the machine guns on Zeros. The second, a larger hole, had been made with a round possessing significantly more energy. Too small for a complete 20-mm round, it most likely was caused by a fragment or ricochet of that higher-caliber shell, which Zero pilots fired from two cannon. There was an “exit wound” flare to the metal on the front of the blade. Both rounds had pierced the blade from behind: The shooter, or shooters, had been chasing the Wildcat. The evidence was consistent with what both Sakai and Southerland had reported: that Japanese Zero pilots had flown firing passes behind the Wildcat.

The Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine is an air-cooled radial with two rows, or banks, of seven cylinders each. One cylinder on the rear of a bank had been heavily damaged, though the cylinder forward and to the right (they are offset so that one does not block the air from reaching another) showed no apparent distress other than from exposure to the elements. Damage to the rear cylinder almost had to be from heavy weapons fire striking it from behind. The top of the cylinder, including the cooling vanes, was missing. A Zero’s 20-mm round could have blown the top off that cylinder, and as I examined the pushrod that had been attached to a valve that was now gone, I realized that Sakai had, as he’d said, spared Southerland. After arming his 20-mm, he aimed for—and struck—the engine. He could have easily aimed for the cockpit.

Moments prior to his bailout, Southerland had an opportunity to shoot Sakai down: The Japanese pilot overshot after a firing pass. Why did Southerland, who had already shot down two Japanese aircraft and out-maneuvered several others, not take advantage of Sakai’s error? He reported that he had tried to fire but had been unsuccessful. Was he out of ammunition, as he himself surmised, or had his guns jammed, as author Sakaida believed? Southerland said he had tried to clear the guns with the recharge mechanism mounted in the cockpit and still had been unable to shoot.

Taylan had seen a wing section on his first visit. A look at the machine guns mounted in the Wildcat’s wing might hold the answer to what had prevented Southerland from firing.

We moved west, up the stream, past thick concentrations of uprooted tree trunks, brush, and debris that presented clear evidence of flash flooding. Rain continued to pour. I wondered how much time we might have to scramble up the slope once we heard the rush of floodwater. My thoughts were interrupted by the sight of the top half of a main landing wheel protruding from the stream bed. Taylan remembered the wing was located uphill from that point. The climb was so strenuous that at one point I turned around, deciding that the route was too hazardous to continue, but Canadian photographer Larry Quesnel, with a 27-pound camera balanced on one shoulder and 30 more pounds strapped to his back, slipped past me and took on the ascent like a mountain goat. In another 200 feet, we came upon a wingtip. Gii, ahead on the slope, called down that a landslide had covered the rest of the wing with dirt. There was no hope of digging down to the wing and no hope of studying the wing-mounted guns. We decided to search the area for ammunition.

It was Gii who found the shell casing. When he held it up, my heart sank. The bullet tip was gone. A spent round was not what I was hoping for. Gii handed it down anyway, and I peeled away the muck. It was a .50-caliber, but what really interested me was that a section of linkage belt was attached. Linkage is stripped away and jettisoned as each round enters the gun barrel chamber. The fact that linkage was still attached to this round meant that it hadn’t been fired.

I cleaned away grime from the end of the shell. The primer showed no evidence of a firing pin’s impact: more evidence the round had not been expended. Then I turned it over and let out a whoop. The shell case had been dented—pierced—at the midpoint. Whatever struck the case had hit with high energy. Southerland reported taking fire both from the gunners on the Betty bombers he was chasing and from the Zeros defending the bombers. One bullet, he said, had cracked his bullet-proof windscreen. Other hits blew open the panels on the top of his wings through which armorers loaded the guns.

Gii’s find had been significant: It proved that at least one of Southerland’s guns still had ammunition.

At that point, we were about halfway up the western slope of the ravine. To return, we decided to continue upward, then make our way back across the ridge top. As I sucked in great breaths of air, any lingering questions I’d had about how the wreck had remained undiscovered for so many decades were erased.

Back at the King Solomon Hotel in Honiara, Guadalcanal’s capital, I placed a 7.7-mm round against the indentation and puncture hole in the .50-caliber shell Gii had found. It fit nicely. Because of the angle at which the tip of the round fit best, the round appeared to have arrived from ahead of the Wildcat. The casing most likely had been damaged during Southerland’s attack on the Betty bombers, but why was the bullet missing? I noticed that the casing was flared at its end. The flare shape of the neck indicated that this round had detonated outside the gun barrel. In piercing the casing, the 7.7-mm round had ignited the gunpowder; that’s why the bullet was gone.

Above the impact point on the casing, the linkage belt had been cracked by the same projectile that had continued on to pierce the casing. The combination of a round that had “cooked off” and a damaged belt had almost surely caused a jam within the ammo box or at the point where the round was to enter the feed channel. Sakai probably owed his life to the Betty crewman who had shot that 7.7-mm round. Taylan gave the casing to the National Museum in Honiara.

The following day, Gii went back alone to the site, this time in search of the cockpit. I was certain it was somewhere near the impact point. It may seem like a minor task to search for a cockpit in a two-acre area, but in that terrain the task is daunting. Gii didn’t find the cockpit, but he did discover Southerland’s .45-caliber pistol. Southerland reported leaving it behind in the aircraft when he bailed out.

Coming upon a crash site is an eerie experience. Maybe it’s the contrast between the stillness of the ruin and the obvious chaos of those final moments. Knowing the story of the dogfight made this encounter even more sobering. When I studied the Wildcat’s damaged cylinder, I could feel, across the span of 60 years, Saburo Sakai’s dilemma: whether to kill an enemy or to spare a fellow pilot amid the appalling violence of World War II.

Author Ralph Wetterhahn discussed the dogfight over Guadalcanal in an episode of the PBS program “Secrets of the Dead,” first broadcast in November 2006. See the program’s website for more information, including video.