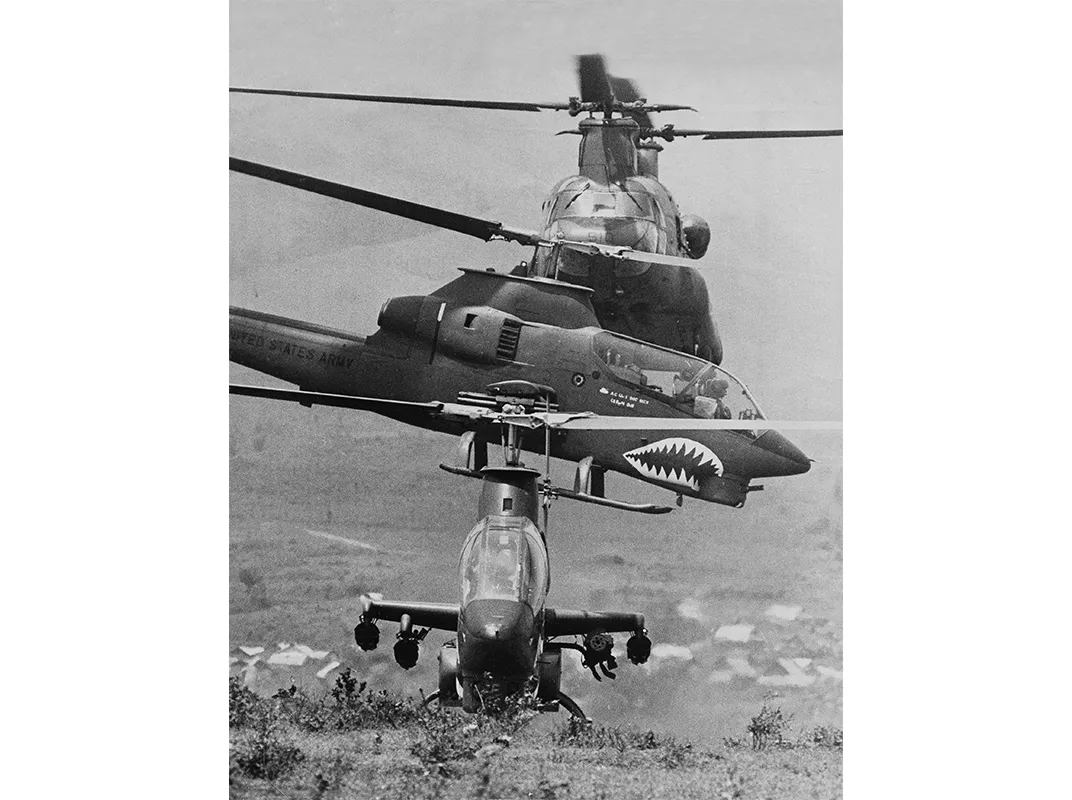

In Vietnam, These Helicopter Scouts Saw Combat Up Close

Cobras and Loaches, two vastly different aircraft, relied on each other to fight the enemy.

:focal(737x296:738x297)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/fd/66fd1f80-63cb-41c3-af2d-f6d9494f8fd5/07p_sep2017_4romero.jpg)

“You were right in the enemy’s face with a helicopter and had to know what you were doing,” recalls warrant officer Clyde Romero of his 1,100 hours flying scout missions over South Vietnam in 1971. “It’s like a street cop going into a bad neighborhood. You can have all the guns, vests, and radios you want, but you need street smarts or you’re going to be dead within an hour.”

Although most combat aircraft in Vietnam aimed for altitudes and speeds that helped them avoid anti-aircraft weapons, U.S. Army crews flying Hughes OH-6A Cayuse helicopters flew low and drew fire—to set up the shots for the Bell AH-1G Cobras circling above. These hunter-killer missions, among the most hazardous of the Vietnam War, tested the resolve of the OH-6 pilots and the aerial observers sitting beside them. Although many were still teenagers, their survival depended on well-honed instincts and razor-sharp reflexes, along with plenty of luck.

In 1965, the concept of helicopter-borne fighting forces was still new and largely untested, and units in Vietnam invented tactics on the spot. The U.S. Army began to use Bell OH-13 Sioux and Hiller OH-23 Raven helicopters, once artillery spotters, to scout ahead of UH-1D Huey formations in the moments before air assaults to gather information about landing zones and enemy locations. Vietnam’s mountainous terrain stressed the underpowered, obsolete helicopters to their limits: They could neither fly fast enough to escape enemy fire nor carry enough armament to pose a meaningful threat. Units in Vietnam began sending UH-1Bs outfitted with rocket pods and machine guns to circle over the scouts at around 600 feet and attack anything that might interfere with the imminent troop landing. But the Hueys proved too slow to do the job properly, and the need to replace both scouts and protectors was immediately evident.

Within that same year, help was on the way. An inventive Bell Helicopter engineer was already at work on the world’s first attack helicopter, and Bell’s decision to keep the project hidden until complete let the model slip into service as a Huey derivative (see “The Birth of the Cobra,” Aug. 2017). In August 1967, the AH-1G Cobra arrived in Vietnam.

The Cobra was fast and deadly. From the rear cockpit, the pilot fired rockets from launchers fixed to the stub wings on either side; the copilot in the front operated a chin turret that held a minigun and grenade launcher. Unlike its troop-carrying ancestors, “a Cobra was like a World War II fighter,” says Jim Kane, who arrived in Vietnam fresh out of Purdue University. “It was a joy to fly.” Kane, who today sells securities in Richmond, Virginia, flew AH-1s in Vietnam from 1968 to 1971.

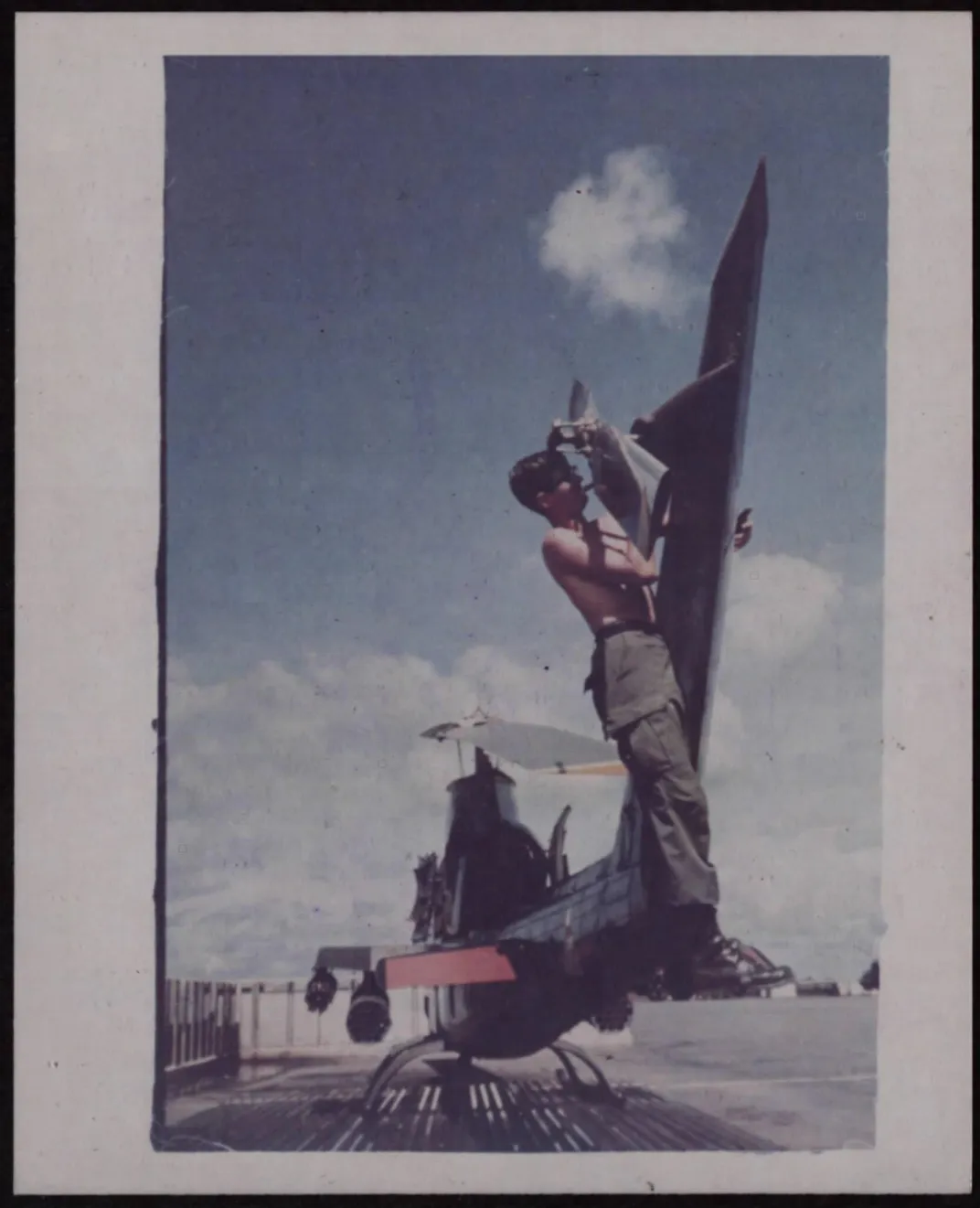

Following a contentious selection process that included allegations of industrial espionage and political favoritism, the first Hughes OH-6A observation helicopters arrived in Vietnam in December 1967. Army troops called the OH-6As Loaches, a contraction of “light observation helicopters.” The ship was unusually light and had plenty of power, perfect for flying nap-of-the-earth missions, and its 26-foot-diameter main rotor made getting into tight landing zones a snap. It had no hydraulic system and its electrical setup was used primarily to start up the engine—simple even by 1960s standards, which for practical purposes meant it was easier to maintain and harder to shoot down than other helicopters. But the light aluminum skin could be easily pierced by rifle bullets, and it also crumpled and absorbed energy in a crash, and a strong structural truss protected critical systems—like the people inside. Loach crews regularly walked away from crashes that would doom others.

As the H-13s were phased out, Loaches were paired with Cobra gunships. Loaches, usually with a pilot and observer and sometimes a door gunner aboard, flew as little as 10 feet above the treetops at between about 45 and 60 mph, scouting for signs of the enemy. Cobras, nicknamed Snakes, flew circles 1,500 feet above the scouts, waiting to pounce on whatever the Loach found. But the Vietnam War was unlike any previous American conflict; there were few real definable frontlines, and combatants needed to know what was happening all around them, all the time. “We operated from fixed bases that were islands, if you will, of allied control,” says Hugh Mills, who flew both Loaches and Cobras in Vietnam from 1968 to 1972, and went on to fly helicopters for the Kansas City Police Department. He recalls: “360 degrees around you was enemy territory, and the ability to work with American and [South Vietnamese] units on the ground really required aviation to be able to look eye to eye to tell the good guys from the bad guys.” Loach-Cobra pairings were sent out more and more frequently, until their main role was to gather general intelligence rather than prepare landing zones.

Missions began every day at dawn, when crews were briefed on where to fly and what to look for. To hunt for encampments, bunkers, or other signs of the enemy, commanders would deploy a flight of one scouting Loach and one supporting Cobra, called Pink Teams. (Scouts were known as White Teams and Cobras as Red; the two colors combine to become pink. In some areas, Purple Teams—one Loach and two Cobras—were also common, as were other variations.) “We were so close to the elephant grass that we’d blow the grass apart to see if anyone was hiding in there,” observer Bob Moses says. Moses, a 19-year-old draftee, arrived in Vietnam in July 1970 for the first of two year-long tours, and later worked for the Department of Veterans Affairs as a therapist and administrator. Even trampled grass was a clue; it meant that enemy troops had passed through the area within eight hours, the time it took for grass to dry upright. Since units were all but permanently assigned to particular areas, they came to know the local geography intimately and could spot anything out of the ordinary. “We were combat trackers,” says Mills. “I followed footsteps. I could see a cigarette butt still burning. I could tell how old a footprint was by how it looked.

“Most of our engagements [we] were 25 to 50 feet [away] when we opened up on [the Viet Cong],” Mills continues. “I’ve seen them, whites of the eyes, and they’ve seen me, whites of the eyes…. I have come home with blood on my windshield. A little gory but that’s how close we were.” As the Loach flew among the trees, the rear-seat pilot in the Snake circling above kept a close eye on the little scout and the front-seat gunner jotted down whatever the Loach observers radioed. Upon encountering enemy fire, Loaches were to leave immediately, dropping smoke grenades to mark the target so that within seconds, the Cobra could roll in. Loach crews were equipped with small arms and returned fire as they fled. They could also use grenades and on occasion even homebuilt explosives; more aggressive units mounted forward-firing miniguns. Cobras generally attacked with rockets, preferred for long-range accuracy, switching to the less-accurate chin-mounted machine gun and grenade launcher only if they were far enough away from friendly troops or if the rockets—AH-1s could carry as many as 76 rockets—ran out. Four troop-carrying Hueys (called a Blue Team) often sat idle somewhere nearby, ready to insert troops if the Pink Team discovered an interesting target—or were shot down and needed rescuing.

Loach and Cobra were in constant radio communication, and because of the intensity of hunter-killer missions, it wasn’t long before pairs in each type knew each other well enough to anticipate the other’s moves. “It had to do with the timbre of your voice—how you talked to other guys on the radio,” says Romero, who arrived in Vietnam in 1970, initially as a Huey co-pilot. (He later transferred to the Air Force and flew F-4 Phantoms, and eventually became an airline captain.) Loach and Cobra crews lived together, and schedulers generally paired the teams with the partners they requested, though given the high turnover rate, that wasn’t always possible. “To this day I am closer to those guys I flew with in Vietnam than my own brothers,” says Mills. “I spent more time with them.”

For most of the war, there was no formal Army training to prepare scout pilots and observers. Army headquarters developed doctrine by building on what worked in the field, rather than the other way around, and each unit in-country did things slightly differently. Though Cobra pilots were trained Stateside, most Loach pilots didn’t take control of OH-6s until arriving in Vietnam. “You had a couple of flights in the Huey, then you rode front seat in a Cobra,” scout pilot Allan Krausz recounts. Krausz was ordered to Vietnam in April 1971, and today teaches Army students how to fly the Eurocopter UH-72 Lakota, a twin-engine trainer. After around 10 hours at the controls of a Loach, the pilots were deemed worthy of flying in combat.

Warrant officer John Shafer was 21 when he arrived on October 16, 1970, to fly Loaches. “I was just out of flight school when I went to Vietnam.” He flew Loaches for the next 11 months, and today is an accountant in Seattle.

The observers and gunners had even less experience. “There was one day of initial training,” says Bob Moses, who was first trained as a tank crewman and then as infantry before a sudden transition to helicopter door gunner. “I went up in a Loach with an M60 machine gun to get used to firing the weapon. That was about it.”

Another such gunner was 19-year-old Joel Boucher, drafted and sent to Vietnam from 1967 to 1969. Boucher quickly discovered that life as a qualified crewman was extremely dangerous. “We flew down along the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” he says of the supply route that wound through Vietnam and neighboring Laos and Cambodia. “The NVA [North Vietnamese army] was everywhere. Each time we went out, we got shot at. One time we ran into hundreds of enemy troops. We thought they were ARVNs [Army of the Republic of Vietnam] until they started running. It was pretty hairy, and we got the hell out of there.” But Boucher got a rush from the missions, and stayed six months beyond what was required of a draftee. Upon returning to the United States, he established a career in the construction industry and settled in rural Sierra City, California.

Other Army pilots, most of whom flew Cobras or Hueys, thought of Loach pilots as a little offbeat. “Scout pilots were a different breed of cat,” says Cobra pilot Jim Kane, who likens his former colleagues to the airborne equivalent of the Tunnel Rats, soldiers who crawled head-first into Viet Cong-built tunnels without any idea what awaited them there. “I was wounded three times and shot down nine times,” Romero reports. “The shelf life of a scout pilot was probably six months. You were killed, shot down, or got scared and quit. I liked it because in the Bronx, I was a ghetto kid. I was used to getting up close and personal with the enemy.”

Mills, who served two tours in Loaches and one in Cobras, was shot down 16 times—all but once in OH-6s. The Army dictated that after 300 hours of flight time, each Loach go through a thorough inspection, but in practice such inspections were rare: Few Loaches survived to reach that mark.

“I had a wingman shot down,” pilot John Shafer says. “They went down in the jungle, and both [members of the crew] survived. I had another lead that went through 150 feet of trees, and they survived.”

Shafer himself had brushes with disaster, and his luck nearly ran out on a mission west of Dak To, near the border with Laos. “I got shot down on my 22nd birthday,” March 27, 1971. “I was flying wing and just dropped into the AO [Area of Operations]. Following the lead, we got peppered with rounds.” The Loach had a bad vibration, but he made it about half a mile before he had to land. “Just as I set it down, the tail rotor spun off. The enemy was moving toward us when a [command and control] ship picked us up. Cobras rolled in and blew the downed aircraft up—taking with it about 15 bad guys standing around it.”

Jim Kane’s Vietnam tour abruptly ended one day in February 1971. NVA troops shot down a Cobra, killing the crew. Kane was dispatched to the crash site in another Cobra with copilot Jim Casher. While they were circling the wreckage, enemy rounds hit their ship. Kane recalls, “The vibrations were so harsh I had to return to base camp at Khe Sanh,” seven miles from the Laotian border. Upon landing, an inspection revealed a damaged pitch link, a rotor head component so critical that had it failed, they too would have crashed.

“We got into another aircraft and went back out. We were about ready to call in tactical air support to blow up the wrecked ship when another Cobra took a lot of fire. So I engaged the enemy, but didn’t make it out of that one.

“We got hit by incendiary .51-caliber rounds, and the phosphorus ignited the Cobra’s hydraulic fluid. The flames covered my boots and lower legs. It was the same for Jim. I still have scars on my legs—it was terrifying. I tried to move the stuck controls and prayed for a place to set down.” It took all of Kane’s strength to pull out of a steep dive, and they crash-landed with a horrific thud. “Jim was unconscious when I helped pull him out of the burning aircraft.”

Kane’s commanding officer flew his command-and-control Huey to the ravine where Kane and Casher huddled. The Huey descended gingerly into a clearing smaller than its main rotor diameter, the aircraft’s rotor blades chopping tree limbs as it descended. Kane and Casher were pulled aboard and returned to Khe Sanh, but the Huey barely made it back; slicing trees had left its blades shredded, and the tail section had almost separated. It never flew again.

**********

The hunter-killer tactic worked well for a few years, but by the time the United States left Vietnam, it was obsolete, says Mills. In 1972, as U.S. troops slowly withdrew, the NVA began a major push that became known as the Easter Offensive. The campaign included the first major use in the war of Soviet-built, shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles. SA-7 Grail heat-seeking missiles could down a Loach before its crew even realized they were under fire. The Cobras high above had a few seconds of warning—they could spot the missile’s exhaust plume—but were all the more tempting because at their higher altitudes they were more easily seen than the smaller Loaches. The North Vietnamese deployed hundreds of the missiles, and from then on, both hunter and killer tried to stay well hidden.

By the end of the war, the Loach’s replacement was imminent. Despite a strong outcry from crews in Vietnam, the Bell OH-58A Kiowa, powered by the same Allison T-63 engine as the OH-6, was being distributed to Army units. Scout crews argued that the Kiowa was nowhere near as nimble as the Cayuse, but scouting flights were changing. The high-low hunter-killer combination gave way to uniform-altitude missions, with all helicopters flying nap of the earth. Kiowas, largely relegated to low-threat cargo and liaison missions in Vietnam, were after the war tasked to spot targets from afar and guide Cobras (and later, Boeing AH-64 Apaches) to good firing spots.

**********

A sobering statistic: Out of 1,419 Loaches built, 842 were destroyed in Vietnam, most shot down and many others succumbing to crashes resulting from low-level flying. In contrast, of the nearly 1,100 Cobras delivered to the Army, 300 were lost.

Both Loach and Cobra have been in production, on and off, in one form or another ever since.

The Loach-derived MD-500 and other civilian variants still roll off the assembly lines at MD Helicopters, Inc., while Boeing produces an upgraded variant, the AH-6 Little Bird, for military forces (including an autonomous drone version). The Little Bird’s weaponry is a far cry from the M60 machine gun carried aboard a Loach in Vietnam: AH-6s can carry miniguns, rocket pods, grenade launchers, Hellfire missiles, and air-to-air Stinger missiles. The AH-6 and its troop-carrying sibling, the MH-6, are still heavily used by U.S. special-operations forces, as everything from airborne sniper platforms to transports inserting small teams to expeditionary light attack helicopters.

The U.S. Marine Corps still flies AH-1 SuperCobras as its main attack helicopter, with the latest version—the AH-1Z Viper— so upgraded and modernized that a Vietnam-era pilot might be hard-pressed to recognize it. Its cockpit teems with electronics and sensors, and its stub wings are heavy with heat-seeking Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, laser-guided Hellfires, rockets (like those used in Vietnam), and even fuel-filled drop tanks. The guidance systems on newer attack helicopters—often working with or even controlling the cameras of reconnaissance drones—have relegated to history the hunter role in the hunter-killer missions. The killer role persists.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/75/4d750035-89e4-4d2f-9ca5-1eec55194aaf/07b_sep2017_loachhunterkillers_live.jpg)