The New Afghanistan Air Force

How the U.S. military is training Afghans to fly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-New-Afghanistan-Air-Force-FLASH.jpg)

With vast distances and forbidding terrain, few paved roads that are too often laced with explosives, and a resurgent Taliban throwing up more roadblocks, Afghanistan is a place where traveling overland is excruciatingly slow and extremely dangerous. Flying is quicker and safer, and, when the destination is a far-flung military outpost or remote provincial capital, often the only way to go.

The Afghan air force was formed with assistance from the Soviet Union in 1921, reorganized by the Soviets in the 1950s, and fully revamped along Soviet lines in the 1980s. When the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan ended in 1989 and civil war broke out, this air force, which once owned 350 aircraft, splintered into groups attached to five warring factions. By the time the Taliban took power in Afghanistan in 1996, only two air groups were left. After the U.S. bombardment in 2001, there were none. What the Soviets built, the Afghans broke into pieces, and the Americans bombed to smithereens.

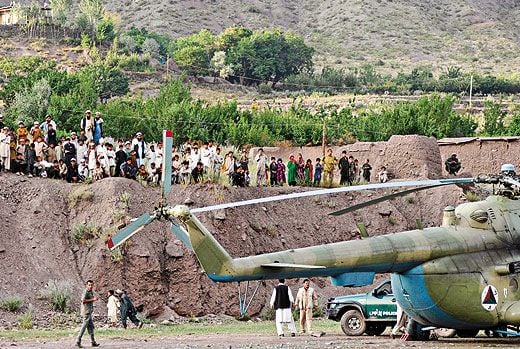

From what remained, the Afghan air force is rising again, this time on the wings of the U.S. Air Force. The more than 700 men and women of the 438th Air Expeditionary Wing, NATO Air Training Command–Afghanistan are training, equipping, and mentoring all levels of the fledgling Afghan service. At Kabul International Airport, there is now an impressive $183 million Afghan Air Force Headquarters and Air Wing, with dormitories, squadron buildings, a medical clinic, and a command center. On the flightlines at Kabul and Kandahar, you will find 40 helicopters—31 Mi-17s and nine Mi-35s—as well as 12 fixed-wing transports: five Antonov An-32s, one An-26, and six Alenia C-27s. By the end of 2010, four more Mi-17s and two more C-27s will join the fleet.

The U.S. mentors started arriving in 2007, and with their assistance, the Afghan air force has increased the number of missions it flies supporting the Afghan army. At first the increase came at a heavy cost: 17 Afghans dead in six helicopter crashes in 18 months. But things are improving. The 438th Air Expeditionary Wing statistics for Class A mishaps—those resulting in the loss of life or aircraft—show one in 2009 and as of October, none in 2010.

THE SOVIET-BUILT MI-17 helicopter is not a graceful-looking machine. In front it has two bulbous dust shields on the engine air intakes, and its fat body perches on two skinny poles connected to bald tire feet—well, at least these tires are bald. Overall, it resembles an overstuffed cartoon chicken with buggy eyes.

Where U.S. aircraft are light, nimble, and sleek, Afghanistan’s refurbished Soviet helicopters are heavy, strong, and ugly. But looks aren’t everything. The Air Force mentors refer to the Mi-17s as “rugged trucks,” and the Mi-35 gunships “rugged tanks.” They say both helicopters are very reliable and simple to maintain.

At Kandahar Air Field, two Mi-17s sit on the apron. Both are about to embark on a mission, and I’ve gotten permission to go along. I am directed to the lead aircraft. Scrambling up its turquoise-painted ladder, I squeeze into the innards, a tight fit since the helo is stuffed to the ceiling with 50 boxes of Remington sniper rifles we will be delivering. But the seats, painted a nauseous yellow, are easy to find. The intense colors, ornate metal handles and grooved panels, padded ceiling, and graceful curved doors give the Mi-17 the feel of a souped-up 1955 Chevy, which would have been a contemporary of this helicopter.

We lift off, hover a few seconds—a brisk wind snaps us to port—rise higher, vibrate lightly, and accelerate forward at a speed that does not overwhelm. With nose down, we skim about 25 feet above a brown desert that changes to burgundy sand dunes sprinkled with sharp green bushes.

Afghanistan has stupendous natural beauty: snow-capped peaks, barren deserts with camel caravans, emerald valleys with rolling hills and rock fences, and sparkling blue-green lakes. To the north snakes the muddy Helmand River with banks of green fields. Farther north is a wall of mountains with hacksaw ridgelines, over which our Mi-17 will soon be climbing. First, however, we must make it past Lashkar Gah.

If Kandahar province is the spiritual home of the Taliban, Helmand province is its fighting home. And Lashkar Gah, Helmand’s capital, is a bad hombre. The Taliban had recently gotten a heavy pounding in Lashkar Gah, so our preflight briefing ended on an uncomfortable question: Are the Taliban there badly wounded and lying low, or are they angry and itching for a rematch? We’ll know soon.

Our pilot, Ataullah (Afghans frequently go by a single name), is middle-aged, and was trained by the Soviets. Flying for 26 years, first for the Soviet-backed Afghan government and later for several factions during the civil war, he has had a lot of experience being shot at. The copilot is U.S. Air Force mentor Lieutenant Colonel Percy Dunagin, a veteran of special operations. Dunagin’s wry humor and sharp eye suggest he’s ready for anything. The pilot and copilot communicate through a translator, an Afghan with chubby cheeks who looks anything but battle-tested. In the back is another mentor, Marine Gunnery Sergeant Carl Cole, manning a Soviet PKM 7.62-mm machine gun in the heavy wind of the open doorway. An intense, no-nonsense soldier who believes being a Marine drill instructor is the perfect job, Cole is drooling-ready for a Taliban attack. On the other machine gun is a young, laid-back Afghan.

“Apache here in seven minutes,” Dunagin tells us over the radio.

The Apache, armed with an M230 30-mm cannon and up to 16 AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, is our aerial guard dog. The Afghan air force is a “beans and bullets” operation: mainly combat-support missions. Today’s flight, ferrying materiel and troops around the country, is typical. Last summer, the Afghans took a step forward, using Mi-35s to provide combat escort for their Mi-17 transports.

“Gunny, see the Apache yet?” Dunagin asks.

Leaning out the door and craning his head around and up, Cole replies, “At 11 o’clock sir!”

As we begin our descent, Cole’s eyes dart over the terrain, which shifts from desolate desert to isolated mud-walled houses. The Afghan gunner is up off the floor now, with both hands on his machine gun. Our helicopter swoops into a British forward operating base, touching down on tiny concrete slabs surrounded by high blast walls. As the Apache circles overhead, Cole jumps out and races to several British soldiers. He returns and shouts into the radio, “Sir, they’re not here. Maybe at the airport.”

We lift off and scoot over the small town to reach the airport. Cole races out and returns with six Afghan soldiers. Then we shoot up and barrel out of Lashkar Gah. A few minutes later, the Apache peels off.

Flying north, our two helicopters crawl over the hacksaw-ridge mountains. In a natural bowl below is a pristine lake with green water. Although poor at maneuverability, the Mi-17 excels at high altitudes, which is crucial here.

On the backside of the ridge, we slide down to a desert plain and land at Tarin Kowt. The six soldiers disembark, and several Afghan soldiers arrive to unload the boxes of rifles into a truck.

Rolling down the gravel runway with 15 combat troops and gear piled to nearly the roof, our helicopter lifts and climbs. In five minutes we’re sailing over a mountain range with sharp peaks. On the other side is a near-vertical drop to a wide plateau. We touch down just outside a small base, and with engines running and blades churning up a vicious sand storm, Cole sprints off with the 15 Afghan soldiers following and soon returns with a dozen carrying large green bags and long poles. Fifteen minutes later, we’ve reached the next base, but we’re forced to circle for 20 minutes until two other helicopters take off.

After we land outside still another small and remote windswept base, there is another exchange of gear and troops. But these Afghan soldiers look different. Their eyes are intense, their bodies stiff. “Commandos,” Cole says with a quick smile. And, with another change in our flight plan, he cracks: “Flying with the Afghans is like playing cards with my brother’s kids—they keep changing the rules during the game.”

We lift off and climb over the mountains, then follow a dry river bed that winds south to the Taliban stronghold of Sangin.

“Apache at 3 o’clock,” Cole tells Dunagin.

Ataullah whips the old Mi-17 into a swoop. Dunagin leans forward. The chubby translator’s face turns green. Cole’s trigger finger taps the side plate of his machine gun. The Afghan gunner’s eyes scan for danger below.

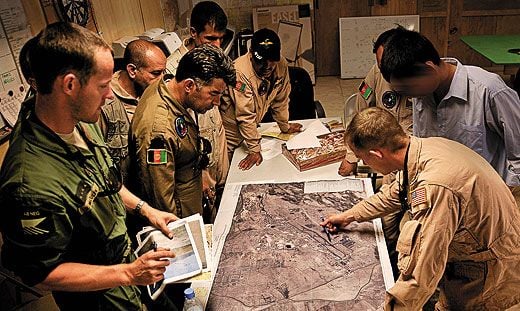

AN ONGOING DISAGREEMENT between the U.S. mentors and the Afghan pilots is that the Americans want more training for future development, while the Afghans want practically none; they want to maximize operational flying. The disagreement over training versus operations is part of a larger cultural difference, with the Afghans less concerned with planning than with actually using their resources. In a culture of scarcity, thinking about the future is a luxury. It’s natural that pilot training would take a back seat to flying. Colonel James Brandon, commander of the U.S. mentors in Kandahar (since redeployed), puts it this way: “The Afghan pilots’ attitude is ‘I’ve been flying Mi-17s for 25 years. The Americans come along with little experience and try to teach us.’ ”

“Building the air force is like building an airplane in flight,” says Brigadier General Walter Givhan, the 438th Air Expeditionary Wing commander. The U.S. mentors squeeze training in when and where they can, but they say it’s not nearly enough. “There should be 25 percent training, but we’re doing only one to two percent on helicopters,” Colonel Brad Grambo, commander of the 438th advisory group, told me. (Grambo has since been redeployed.)

This operational force could use the instruction. While flying from Kandahar to Lashkar Gah, Dunagin had to use his radio to explain to the crew members in the other Mi-17 how to re-program their radio. And immediately after landing at Tarin Kowt, map in hand, he pointed out to the Afghan pilots that they had just clipped the corner of the field’s gunnery range. Afghanistan President Hamid Karzai, who is flown in a formation of three Mi-17s, knows first-hand how badly further training is needed; after a particularly rough landing that almost killed him, he went back to flying on U.S. aircraft. After the presidential detail got the training they needed from the Americans, Karzai is now back with all-Afghan air crews.

The Air Force mentors say the Afghan pilots are excellent stick-and-rudder fliers. But because of their limited training, their skills are restricted to fair-weather and daytime flying—nothing out of the ordinary. But they have recently started training and operating at night, and in August a crew with night-vision goggles made the first night flight in a blacked-out Mi-17. This ability will enable the air force to fly the president in darkness, should it become necessary to hide him.

Today, Captain Robert Leese, chief of public affairs for the 438th Expeditionary Wing, says that the U.S. Air Force is providing the Afghans with more simulator time and training.

FOR ONE WEEK in the winter of 2008, a selection board composed of two U.S. colonels and one Afghan general met in the Kabul airport to review the applications of 128 Afghan candidates for pilot training in the United States. All applicants were military officers with at least a high school degree. Each was given 15 to 20 minutes to address the board.

“What we were looking for was a high level of motivation—and proof!” says mentor commander James Brandon, who was on the selection board. “We looked into their background, into their educational level. We looked for that stick-with-it in their lives that showed they had the tools to succeed.”

The board initially picked 28 candidates, and then 17 more. Through a separate process, the National Military Academy of Afghanistan contributed 20 additional students. The selected candidates came from diverse military backgrounds: administrative officers, logisticians, infantry officers, pharmacists. Some had attended Kabul’s Air University, which the Taliban later closed, forcing the students into hiding.

That first group of candidates was sent to Lackland Air Force Base in Texas for English instruction, and then to various other U.S. bases for training in either rotary or fixed-wing aircraft.

A year later, the training continues. I am at the shiny new terminal at Kabul International Airport, where a group of 10 Afghan men, ranging in age from early 20s to mid-30s, are about to fly to Dubai, then transfer to a flight to San Antonio, Texas. From there, they will be driven to Lackland for English language instruction. (Last year, the U.S. Air Force also set up Thunder Lab, an English immersion program for Afghan pilot trainees, at the air base in Kabul.)

The men, five dressed in subdued suits and the others in neat casual clothes, look ordinary, but they’re not. And for them, today will always remain extraordinary.

“At first today I was very excited,” says Abdullah, a stocky man with closely cropped hair. “Now I am very sad. I’m leaving my family for a long time.” Most of the students will be away from Afghanistan and their homes for nearly two years.

Ibrahim, dressed in a conservative dark suit, takes a different view. “This is very important for our country,” he says, “and very important for my family. We can’t fail.” One day the NATO forces will pull out. If the Afghan air force fails, the government it is fighting to defend could fail as well.

And the air force has a big problem: Its pilots are getting old. Ataullah, my Mi-17 pilot, is 48—and only three years older than the average Afghan air force pilot (by comparison, the average U.S. Air Force pilot is 33). The service desperately needs young pilots.

The men make their way across the glossy floor toward the departure lounge. As the line inches forward, their faces show their jumbled emotions—joy, distress, determination, gloom, excitement, trepidation. Kuldeep Kappor, an Afghan-American instructor at the Kabul Air Force Training School, offers quiet words of fatherly encouragement. U.S. Major Beth Kettle, the executive officer of the 438th (since redeployed), boisterously proclaims her faith in the men and thrusts her hand out for pumping handshakes. Handshakes? At the Air Force Training School several days earlier, I had asked a dozen students headed for pilot training: “What is your greatest fear when in the United States? Conquering the English language? Passing the rigors of pilot training? Missing your wives and families for two years?” These Muslim men said their greatest fear was shaking a woman’s hand.

Once at Lackland, the students will endure the rigors of intensive English language lessons for nearly a year. Then the rotary students will head to Fort Rucker, Alabama, for flight training by Army instructors, and the fixed-wing students will be instructed at Columbus Air Force Base, Mississippi.

LAST JUNE, the United States’ efforts to help build Afghanistan’s military got some bad publicity: FoxNews.com reported that a total of 46 Afghans who had come to the United States since 2002 for training in a variety of military skills had gone missing from Lackland over the years. David Smith, Lackland’s chief of public affairs operations, says that all Afghan students who had left the base without authorization had been reported to the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. According to the Toronto newspaper the National Post, 22 of the 46 were later found to be in Canada (some were found on Facebook). Others were found in the United States and either deported or given conditional U.S. residence status. An undetermined number have still not been found. Smith says that Lackland is still training Afghan military personnel. Since the AWOL alert was issued, he adds, “the Afghans have added a resident liaison officer to help students work though their issues.”

As of October 2010, a total of 109 Afghan students have come to the United States for English instruction and training in flying. Of them:

- 17 completed instrument flight school,

- 2 completed helicopter training,

- 1 completed fixed-wing training, and

- 3 have competed all of their U.S. training and are back in Afghanistan.

Stewart Nusbaumer has reported on more than a dozen wars over three decades and has spent nearly a year in Afghanistan covering the war as a freelance writer.