Thuds, the Ridge, and 100 Missions North

How the Republic F-105 got good at a mission it was not designed to fly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jet-Thud-F105-Article9-FM09.jpg)

At the 1854 Battle of Balaclava during the Crimean War, British cavalry were ordered to attack withdrawing Czarist artillery brigades. By the time the order cascaded down the chain of command, however, it misdirected the British horsemen into a hail of fire from Russian guns. The debacle caused a furor in England, and inspired Alfred, Lord Tennyson, to pen “Charge of the Light Brigade,” with its mournful refrain: Into the valley of Death rode the six hundred.

Just over a century later, something like that infamous charge was performed in modern dress, this time with airplanes, and with the Russian weapons hidden in the forests of North Vietnam. And this time the action was not completed in a single day, but recurred, every morning and afternoon, weather and politics permitting, for more than three years. Charge of the Light Brigade, meet Groundhog Day.

The Republic F-105 Thunderchief, the main aircraft involved in the drama, had never been intended to play the role of a strategic bomber. Rather, it had been created to make a single, low-level nuclear strike—to use its potent stinger once, then die, like a bee.

In January 1952, the U.S. Air Force was seeking such an aircraft, one that could penetrate enemy territory and take out military bases with both conventional and atomic weapons. At Republic Aviation’s Farmingdale, Long Island plant, such an airplane was already taking form as Advanced Project 63 under legendary Russian émigré designer Alexander Kartveli. Republic Aviation was awarded the contract, and the YF-105A first flew on October 22, 1955.

The F-105 seems to have accreted around the single Mk-28 thermonuclear bomb it would carry in a fuselage bomb bay. About the size of a mansion-grade hot-water heater, the weapon could deliver anything from 10 kilotons to more than a megaton of explosive power. The Republic design team took the tubular fuselage of the company’s F-84, a fighter-bomber used extensively in the Korean War, and gave it an area-rule pinch at the waist to improve the transonic behavior of what would become a Mach 2-plus airplane. Wing-root inlets were swept forward to prevent engine stall, and a new Pratt & Whitney J-75 turbojet replaced the proposed J-71. In an era when guns were so 1950s, compared with missiles, someone added a 20-mm Gatling in the Thunderchief’s nose.

In 1957, a year before the F-105 entered service, the Air Force had Republic upgrade it with new navigation electronics and radar for all-weather operations, a fire-control system, and a more powerful version of the J-75 engine. The changes yielded the fully evolved, stiletto-shaped F-105D. The aircraft’s 45-degree swept wings measured, tip to tip, not quite 35 feet—about the same as a Piper J-3. But it was no trim little thing. The -105’s vertical stabilizer towered 19 feet above the ground, about the height of the vertical stab of a Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress, and its fuselage was only about 10 feet shorter than the Fort’s, making the F-105D the largest single-engine jet aircraft ever sent to war.

With some fanfare, the D model entered service in September 1960. Wrote a New York Times reporter: “The Air Force rates the Thunderchief as the most devastating system of destruction ever controlled by one man.” Accordingly, only high-time fighter pilots were sent to Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada to learn how to wield that power. “You had to have a thousand hours before they let you fly the thing,” recalls Michael Cooper, a Nellis grad. He’d won his wings in 1955, and had been flying North American F-100s. “We transitioned to the -105s in the summer of ’63. I went down to Mobile, Alabama, and picked up a brand-new airplane. Took it home.” Cooper still remembers the serial number, 62-4372. The aircraft flew until 1980, when it crashed during a NATO training exercise in Denmark.

“It was a great airplane,” says Cooper. “Not much of a fighter. But it was so much faster than everything else. The Navy F-4s, we’d fly right through their formations,” closing from behind.

According to Thunderchief pilot Michael Brazelton, the heavy fighter could make “860 knots on the deck, well above the speed of sound. Trouble with going so fast so low is that the canopy starts to melt. We had a double canopy, with coolant between the layers.”

Raw performance aside, the Thunderchief was “a pretty amazing airplane,” says Ed Rasimus, who went through a later class at Nellis. “We used to do a nuclear profile [training flight]. There was a radar mode you could fly at 500 feet. Gear and flaps up, you’d engage the autopilot, set up terrain avoidance, fly 400 miles, deliver a [mock] nuclear weapon on a target, and take the stick back at 200 feet on final.”

The Nellis grads were sent off to the frontlines separating East and West. Some went to bases at Bitburg and Spangdahlem, West Germany, others were assigned to Yokota Air Base in Japan. From the bases in Germany and at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa and Osan, South Korea, the pilots began standing alerts, nuclear weapons tucked into their airplanes’ bomb bays or hanging from wing pylons, waiting for the terrible moment to arrive.

The moment never came. Fate had something else in store for the Thunderchiefs and the men who flew them.

On the nights of August 2 and 4, 1964, two U.S. destroyers, Maddox and Turner Joy, reported an attack by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. Exactly what occurred has been debated for a generation, but, whether real or contrived, this became the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, and a call to war.

“We went down the next day or two,” says Cooper, whose F-105 squadron was based in Japan. The pilots flew into the Royal Thai Air Force Base at Korat, Thailand. “Wasn’t much there when we got there,” he says. “Camp Friendship was the U.S. Army’s. Thais had a little flying school on the other side of the field.” Cooper chuckles, remembering those early days. “We come in, a fighter squadron and all its munitions. C-130s coming in every 15 minutes dropping something out.”

Those were uncertain times. No one knew if U.S. involvement in Vietnam would trigger Chinese or Soviet intervention. “We were doing all sorts of lines [nuclear missions] on all sorts of maps for all sorts of targets,” says Cooper.

Korat soon became a comfortable little Air Force city. For a time, the -105s—the nukes in the bomb bays replaced with fuel tanks—provided muscle for the CIA’s campaign against Pathet Lao insurgents. Until 1966, the Thai and U.S. governments denied that the aircraft were operating out of Thailand, but it was an open secret. Thunderchiefs were hard to miss.

The aircraft acquired the usual derisive nicknames. Where Republic’s P-47 had been the Jug, the F-105 became the Thud. The origin is unclear. Some said “Thud” echoed the sound of an F-105 crashing in the jungle. Some attributed it to Chief Thunderthud on the “Howdy Doody Show.” As with many such sobriquets, Thud quickly became a term of endearment. The -105 might be a bear to maintain, but the pilots loved its power, speed, and resilience. Thuds came home with large bites taken out of them by missiles and flak. The pilots prided themselves on doing the work of a five-man bomber crew at or beyond the speed of sound, 100 feet above the jungle, flak and missiles and MiGs everywhere.

Cooper’s squadron was in Thailand about 30 days before rotating back to Japan, where the pilots resumed their nuclear watches. When they returned to Thailand in the spring of 1965, it was to a second field at Takhli.

“Takhli in October ’65 was not much more than when the Japanese left,” recalls Dick Guild (rhymes with “wild”). The base had been built by the Japanese during World War II. “When I first got there we had a mess hall, officers’ club where you could make sandwiches,” says Guild. “We slept in hootches, eight beds to a side. Common washroom, the sinks filled with crickets. No air conditioning. Mosquito netting. Movies in the mess hall.” He grins. “It reminded me of Terry and the Pirates.”

He prefers the rough Takhli to the comfortable, Americanized base it became, with swimming pools, a new officers’ club, and individual air-conditioned apartments for the pilots. “Living alone and flying combat is really a bad idea,” he says.

By February 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson had approved Operation Rolling Thunder, a bombing campaign by the Air Force and the U.S. Navy intended to crack the North Vietnamese spirit. Because the two services did not play well together, planners divided North Vietnam into six route packages, or PAKs, later splitting the sixth into VI-A and VI-B. PAKs I, V, and VI-A belonged to the Air Force, and II, III, IV, and VI-B were the Navy’s. Da Nang-based Marines would share PAK I with the Air Force.

All seven areas were bad, but VI-A was the worst. Bristling with anti-aircraft defenses, it contained the main rail and road routes to China, which intersected at Hanoi. Pilots called Hanoi “downtown,” where, as the 1964 Petula Clark hit put it, “everything’s waiting for you.”

Superposed upon the PAKs were complicated rules of engagement, which put such targets as power plants and airfields out of bounds. Nothing in a 30-mile circle around Hanoi or a 10-mile circle around Haiphong could be hit. The ships pouring supplies onto the Haiphong quays were also off limits. And heaven help the hapless jock who strayed into a 20- to 30-mile buffer zone along the Chinese border.

Pilots could defend themselves from attacking MiG fighters, but could not hit them on the ground. Surface-to-air-missile sites were fair game if they were active; while under construction, they were safe. Targets were selected in Washington, often over a White House lunch, when the president and secretary of defense, sometimes aided by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, mulled over the military’s proposed target list, picked some out, and had them relayed back down the line to Saigon and, eventually, to Korat and Takhli. Once something became a target, it remained one. If it wasn’t wrecked on the first raid, it would be attacked again and again until it was. Most Sundays the Thuds went downtown.

Rolling Thunder escalated so gradually that the North Vietnamese were able to harden their defenses and hide critical supplies. Their web of anti-aircraft guns and Soviet surface-to-air-missile sites was soon the most sophisticated air defense system in the world.

The word among Thud pilots was that by their 66th mission they would have been shot down twice and picked up once. Put another way, they had about a 60 percent chance of completing the 100 missions north they were required to fly. (Their frequent sorties into Laos didn’t count.) For pilots on permanent assignments, 100 flights took about six months to accrue. For those rotating in from Japan, the requirement could take a couple of years.

Whether on permanent or temporary duty, a Thud pilot knew that he was in a knife fight with his good hand tied behind him.

At first light, the morning forces at Takhli and Korat would begin assembling for breakfast, briefing, and a good deal of study, with each four-ship flight learning what fragment, or “frag,” of the total day’s work Saigon had given them. By mid-morning, the pilots were on their way to their aircraft, wearing about 80 pounds of G-suit, parachute, and survival gear. Once the fliers were strapped into their machines, they taxied to an ordnance pit, where ground crews removed the red-flagged pins from the bombs.

“On PAK VI, we’d have eight [750-pound bombs] on the wings,” says Guild, or combinations of 500-, 1,000-, 2,000-, and 3,000-pound bombs. “I liked the 3,000. They didn’t work for bridges, but for taking out flak pits….” He smiles, his hands describing a big blast wave propagating outward. “I dropped CBUs [cluster bombs]. You could see them down there, pop pop pop pop, but the guns just kept shooting.” He wasn’t fond of napalm. “God knows where it’s going to go.”

“The F-105 flew like a heavy T-38,” says Brazelton. “Even with bombs on it, I could do an aileron roll. My favorite [configuration] was a centerline tank and a 3,000-pounder under each wing. A lot sleeker.”

The classic PAK VI mission, says Rasimus, was “always a package, 30, 40, 50 airplanes,” including a Douglas EB-66 electronic countermeasures aircraft, F-4 Phantoms to fight off MiGs, and Wild Weasels, two-seat F-105F or -G models used to counterpunch anti-aircraft defenses.

Once airborne, the four-Thud formations headed for a herd of Boeing KC-135 tankers flying 30-mile-long racetrack orbits over Thailand. “Each [formation] had their own tanker,” says Rasimus. “They’d fill everybody up. Tanker would head north, take us up over Laos, about halfway to the target. We’d quickly cycle through again and drop off with full fuel. It took about half our gas to get up there,” says Brazelton. “But once refueled, we could fly a long way, a thousand miles.”

The F-105s would then head into North Vietnam, flying at 18,000 to 20,000 feet. Going into PAK VI, the pilots followed two main approaches. One took them out over the Gulf of Tonkin, where they then turned to the attack. The other took them along a mile-high branch of the Day Truong Son (Long Chain of Mountains). Paralleled on the south by the Red River, this narrow complex of karsts and dense-canopy forest points southeast toward Hanoi. Americans called it Thud Ridge, after the men who were lost there and the F-105 detritus littering its rough slopes.

“We flew down the center of Thud Ridge,” recalls Guild. “If we skimmed it to the south we would get hammered out of Phu Tho and Quan Tri. If we skimmed it to the north, we would get hammered from that valley. I think it was just too hard for them to put AAA guns or SAMs on Thud Ridge.” Later in the Rolling Thunder campaign, a heavy-lift Russian helicopter added weapons to the ridge.

“We’d go to a target line abreast,” says Cooper. “The Thud had a pretty good automatic nav system if you were bombing Vladivostok with nukes, but if you’re bombing bridges up in the mountains, you can’t even tell which valley or which slope.”

“In the cruise in, we’d be on altitude hold, autopilot,” says Rasimus. “Not a whole lot of threat. Once down, it was hand flying. You’d want to be jinking a little bit. In the target area at 540 to 600 knots: 4-G pull up, zoom climb, 4-G pull down on the [30- to 40-degree] dive angle, drop it at about 3,000 feet above ground, down to about 1,000 [feet above ground level], then 4 to 5 Gs recovering. After they left the target, it was everybody for himself.”

Enthusiasts then had a chance to go trolling for things to strafe with the Gatling gun. It took a while for everyone to see the folly of risking a multimillion-dollar airplane to whack a 10,000-ruble truck, or pitting the 20-mm Gatling against 57-mm artillery, or looking for dogfights. “A lot of people were lost who shouldn’t have been, screwing around with a MiG-17,” says Cooper. “We could depart from it faster than a missile could track, separating at the speed of light.”

That blazing speed made the Thud difficult to protect, says Brazelton. “One time they were thinking of sending F-4s on MiG escort. As we approached the target, we went a little faster, then a little faster. Pretty soon they couldn’t keep up with us. We were happier when the escorts stayed away. If there were any MiGs up there, there were plenty of -105 pilots eager to pull the trigger.”

Even with the disadvantages of the F-105’s weight and poor turning ability, when the smoke cleared, it was Thuds 27.5, MiGs 22, with 24.5 Thud victories credited to that fossil nose-mounted gun.

Going in or coming out, if someone got hit—and someone almost always did—the Thuds usually kept moving. “In 1966, when a guy got shot down, if he wasn’t picked up in the first 90 minutes, he wasn’t coming out,” says Rasimus.

“In PAK VI, if someone went down across the Red River, we’d continue on, but the wingman would stay with a crippled bird,” says Guild. “If someone went down on the way out, we would continue egress, try to get to him later. You don’t want to pinpoint the downed guy.”

Brazelton had almost finished his 100-mission tour when he got smoked. It was August 7, 1966, north of Hanoi. “I was dropping CBUs on a 120-mm anti-aircraft site,” he says. “A 57-mm must have hit me right in the belly. I rode it for a minute or so, told them I was ejecting. They couldn’t do anything, just too many guns. I didn’t ask them to.” (Brazelton spent the next six and a half years as a POW.)

Coming off the target, the F-105s stayed together and headed for the tankers. They took enough fuel to get back to base, where, some four hours after their takeoff, the afternoon shift was preparing the next charge against the Russian guns.

The 388th tactical Fighter Wing settled into Korat, the 355th into Takhli. As pilots and aircraft were lost at the rate of five or six a week, replacement air crews and aircraft flew in, the Yokota units to Takhli, Kadena units to Korat. Thud pilots from Europe also arrived.

There were rivalries. In his memoir, Thud Ridge, Colonel Jack Broughton, then vice wing commander at Takhli, refers to Korat as the “Avis wing.” Over at Korat, the word was that Takhli had some people interested in becoming heroes. Some accounts make both wings sound like Texas Aggies about to play the Longhorns. There are tales of the “pressure bar” at Takhli, where pilots recited stuffy Pentagon nonsense about their incompatibility with “normal management techniques,” yelled a few obscenities, sang some unprintable songs, and shattered their bottles on the floor.

The late Gene I. “G.I.” Basel, in his 1982 memoir, Pak Six, describes impromptu wakes at Takhli for lost comrades. Pilots from the day’s raid would run a gauntlet of hurled beer bottles, trying to reach the far wall, called Thud Ridge, unscathed.

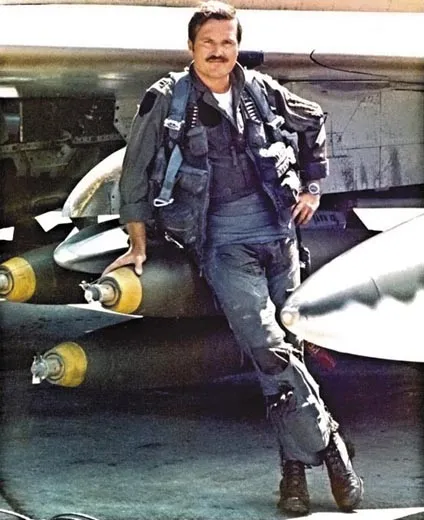

Both bases adopted Australian bush hats and kept their missions tallied on the rims. Pilots tend to be superstitious. That bush hat couldn’t be left on the bed or on the dresser. Crickets in the wash room were not to be smushed. At Korat, a mustache rendered the pilot bulletproof; shaving it off was tantamount to suicide.

“We drank more than we needed to, but I always tried to get six or eight hours sleep before a mission,” says Cooper. “A hundred missions in six months: That’s 16 or so sorties a month. Every 16 days you’d get four days off. I tried to make Bangkok the center of my universe.”

Guild’s main memory of Takhli is “being tired all the time.”

Behind the wild-bunch reputation, the Thud crews were a pretty serious lot. “I tried not to think big thoughts in those days,” says Cooper, “but I really wondered whether I’d see my kids again.” He also worried about the prisoners of war. “A bunch of good buds up in that hell. I thought about that a lot.” According to former POW Mike McGrath, now historian of a POW organization, of 207 fighters and fighter-bombers downed over North Vietnam, 99 were Thuds.

The Thud experience was not for everyone. “We had people, when it came to the point where they had to fly, they’d quit,” says Rasimus. “One kid got shot down on his first mission, got picked up, came in when he got back, and handed in his wings.”

There was good reason to fear the daily gallop into North Vietnam. “The losses were appalling,” wrote Rasimus in his 2003 memoir, When Thunder Rolled. “The class of nine that had been six weeks ahead of mine at Nellis lost four. The first short-course class of ‘universally assignable’ pilots lost 15 out of 16, all either killed or captured…. For every five pilots that started the tour, three would not complete it.”

Wrote Basel in his book: “I walk the streets and still grieve for them, and for those that did return, for all the others and for myself…. What was it all about? This magnificently orchestrated event that accomplished nothing. Casualties of this monstrous charade, we ask, For What?”

For others, the combat habit acquired in Thuds proved impossible to kick. No one was required to return to the unfriendly skies of Southeast Asia, but many did. Karl Richter flew his 100 missions out of Korat, then signed up for 100 more. Near the end of the second tour, he was killed on a run into PAK I. Several years after their first 100 missions, Rasimus, Cooper, and Guild also came back for another 100, this time in F-4 Phantoms.

Some returnees might have hoped to finish the thwarted work of Rolling Thunder. But most seem to have been drawn back to the metaphorical Balaclava by memories of the adrenaline rush, the camaraderie, the exhausting, exhilarating life spent on the edge, doing work only the brave can do.

At the same time, the Thud pilots understood that they risked everything to achieve results that were often questionable. It reminded Rasimus, who grew up in Chicago, of stealing hubcaps.

Long-time contributor Carl Posey writes from Alexandria, Virginia.