“We’ve Been Hit”

F/A-18 vs. surface-to-air missile: Guess who won.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Above-and-beyond-9-1-2012-1_FLASH.jpg)

Saddam Hussein’s invasion of neighboring Kuwait in August 1990 caught the world by surprise. His aggression triggered Operation Desert Shield, which kept his army from advancing farther. When it became clear that Saddam was not going to back down, Desert Shield got cranked up a few notches.

In January 1991, Marine Corps squadron VMFA(AW)-121, the Green Knights, stationed at El Toro, California, was ordered to Shaikh Isa Air Base on the island of Bahrain for the battle over Kuwait. The squadron had formerly flown Grumman A-6 Intruders and was now flying brand-new two-seat F/A-18D Hornets, which they had received only six months earlier. The upgrade from single-seat Hornets to two-seat night-attack versions, which in the Marine Corps enabled an extra pair of hands and eyes in the form of a weapons and sensors operator (WSO) in the back seat to take over tasks and help the pilot look for the enemy, was like moving up from Curtiss Jennies to Jedi Starfighters. By the end of January, we had on base a dozen aircraft and 200 Marines, including 12 pilots and 12 back-seaters.

Once settled in at Shaikh Isa, the Marine Corps resurrected the Fast FAC (forward air controller) concept from the Vietnam War. Just like the F-4 Phantom IIs did, the two-seat F/A-18D would locate enemy targets, mark their locations with white phosphorus rockets, then direct other aircraft to bomb them. The Hornets were armed with phosphorus rockets from wing to wing, but carried only the bare minimum of air-to-ground ordnance: a 20-mm, six-barrel gun in the nose and one 250-pound bomb on the centerline.

Upon 121’s arrival at Shaikh Isa, the pilots and WSOs were paired up. I would crew for Major Ken “Cheyenne” Bode, a salty, single-seat F/A-18A pilot on the group headquarters staff. Cheyenne, who was assigned to fly with the Green Knights, was a great guy with a wealth of experience.

A bonehead captain and former F-4S radar intercept officer, I had been chosen for the very first class of students in the new F/A-18D, which meant I had a whopping five months of experience in the Marine Corps’ latest whiz-bang airplane.

My first flight with Cheyenne established a pattern. After takeoff, no sooner was the landing gear up and I was contacting Departure Control when Cheyenne came up on the inter-cockpit communication system. “Hey Bubba.”

My call sign was Ping, but for some reason, to Cheyenne I was always Bubba. “Don’t pull the handle, because in a few seconds there’s going to be smoke in the cockpit.” I didn’t say anything, but I was thinking What the…?

Seconds later I removed my oxygen mask and—sniff—there was smoke in the cockpit. Cheyenne was having a cigarette. He smoked all the way to our KC-130 aerial refueler. Then, after the mission, he smoked all the way back to Shaikh Isa.

And so it went, day after day after day.

“Departure control, Combat two-one is airborne, climbing to one-zero thousand.”

“Combat two-one, departure control, radar contact.”

“Hey Bubba.”

“Yeah?”

“Don’t pull the handle. There’s going to be smoke in the cockpit.”

“Roger that.”

On Thursday, February 21, 1991, my takeoff with Cheyenne was the usual.

“Departure control, combat four-one is airborne, climbing to one-zero thousand.”

“Combat four-one, departure control, radar contact.”

“Hey Bubba. Don’t pull the handle….” and “Roger that.”

However, on that particular afternoon, our section stumbled upon the mother lode of Iraqi targets: four tanks and eight artillery pieces 45 miles northwest of Kuwait City, heading south. At the time we found them, there were no aircraft on station for us to control. Worse, the next section of potential bombers wasn’t supposed to check in for another 30 minutes.

What were two Fast FACs to do?

Cheyenne came up on the com system and asked me if I would be uncomfortable leaving our altitude sanctuary of 10,000 feet and descending to strafe the targets.

“I’m four feet behind ya, Cheyenne.”

Cheyenne quickly briefed our wingman on the strafing game plan over the radio, then rolled inverted and dove for the ground.

What followed was an unnerving ballet of two F/A-18Ds strafing Iraqi tanks and artillery from barely 1,500 feet above the ground as tracers whizzed by our canopies.

We were pulling off a strafing run, and I was contorted to the left in the back seat, checking our seven o’clock position, when Cheyenne happened to glance back at our five o’clock and saw the tell-tale white corkscrew of smoke from a heat-seeking surface-to-air missile. He broke to the right, simultaneously ejecting flares. But it was too late. The missile flew directly up our right exhaust pipe and exploded. The jet actually shook.

Cheyenne—a man of few words—said, “Bubba. We’ve been hit.”

“Yep” (I was not much of a talker either, at least at the moment).

Instantly, Cheyenne pointed the nose toward the ocean. We began climbing back to 10,000 feet. After our wingman visually inspected our jet, he reported that our right “turkey feathers”—the drag-reducing, interlocking metal panels that surrounded the exhaust—were mangled. Other than that, he could see no external damage. We began numerous inter-cockpit checks and agreed to shut down the right engine for the return flight to Shaikh Isa.

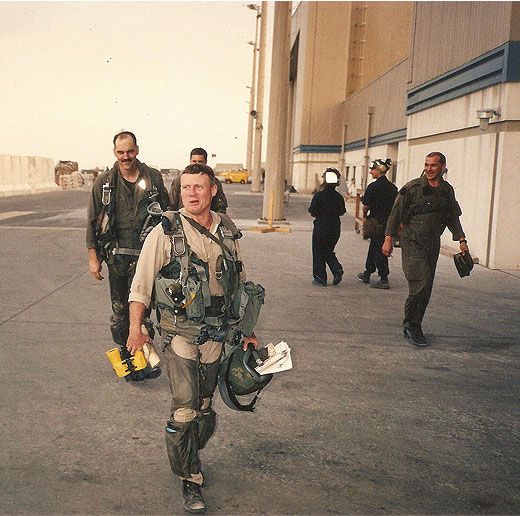

We made an uneventful landing and rollout. As we taxied back into our line, there must have been a hundred enlisted Marines running out to our Hornet. They had heard that a wounded jet was returning. It brought tears to my eyes.

I tried to imagine that Iraqi gunner back on the ground. I pictured him watching his missile go right up our exhaust pipe and explode—then seeing our jet simply fly away. In my mind, he would look at the missile launcher in his hands, throw it down, and jump on it, screaming, “You Russian piece of sh*t!”

Whenever the naval aviation community heard of a cruel injustice, the older, more experienced guys would shrug their shoulders and say, “That’s the breaks of Naval Air.” In September 1993, Cheyenne Bode died of leukemia. For me, it was hard to reconcile Cheyenne’s surviving a surface-to-air missile and then dying from cancer as just a bad break.