Jill Tarter Believes

…we have company in the universe, and we should find it.

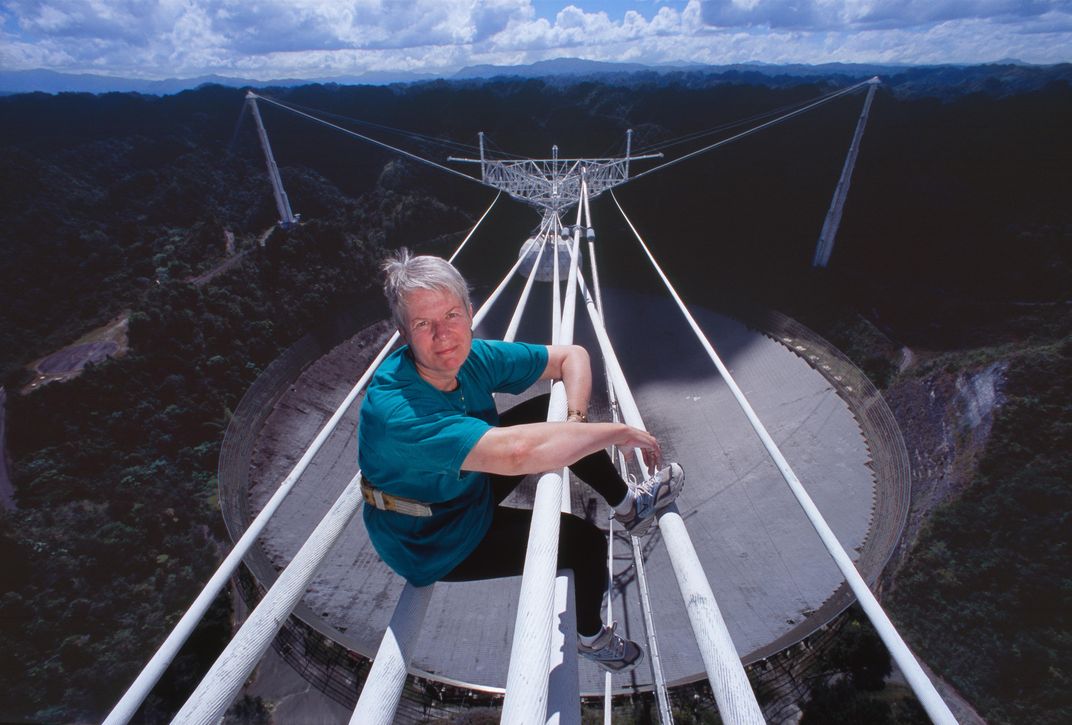

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/9c/3b9c7bd4-7710-48d3-ad18-917f3d8455f4/09b_aug2017_jillsantenna_live.jpg)

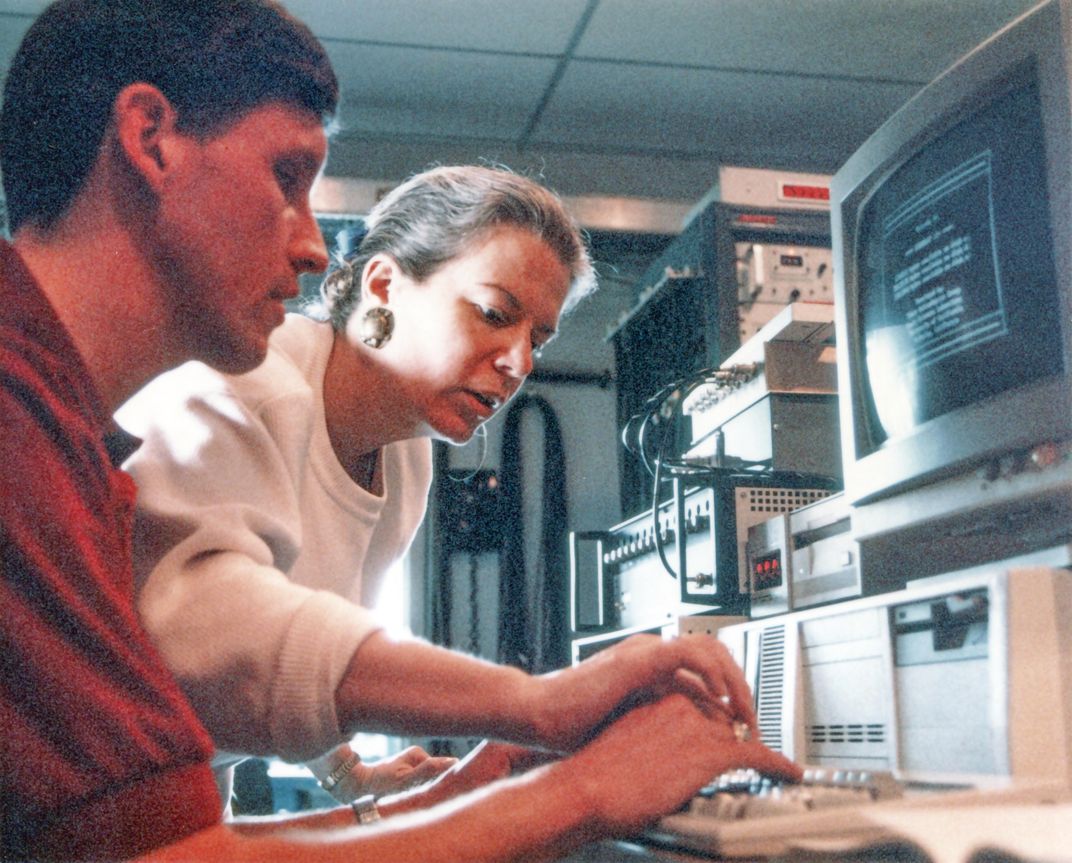

It is 1 a.m. on March 10, 2014, in Northern California, and Jill Tarter peers from the doorway of a dorm in the Hat Creek Radio Observatory residence hall. “It’s beautiful out there right now,” she says. She steps out and onto the cold-steeped cement. The mosquitoes that ordinarily plague the area around the observatory, home to the SETI Institute’s Allen Telescope Array, have all gone to bed. Tarter looks up.

Above hangs a clear, dark sky. “I can’t even find the North Star,” says Tarter. “I’m going to go get my glasses.” She has hardly reemerged with her spectacles when she rushes back inside for her iPhone. “I think that’s Mars,” she says, pointing at a bright reddish dot. After her celestial chart app boots up, she points the screen toward the sky, scanning across a quadrant. Maybe that space is home to planets, which maybe are home to biology.

This scene is almost too easy a mirroring of Tarter’s childhood memories. Looking up from the deserted beaches of southern Florida, she was certain that an alien child was looking at our sun. She has this thought over and over. It is the kind of Groundhog Day observation that keeps her motivated to continue the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, despite the vastness of the universe, the brevity of human life spans, and governmental desire to spend money on missiles instead of science.

A thousand yards away, the Allen Telescope Array—Tarter’s dream observatory, or at least a version of it, made for and dedicated to SETI—scans the sky in search of intelligent life long after she has returned to sleep (see “Can We Hear Them Now?,” June/July 2007). The idea for the array came from a series of workshops held from 1998 to 2000. These posh gatherings, collectively called SETI 2020, plotted the route of SETI research for the next 20 years. While scientists, with their university salaries, don’t expect cushy conferences, Tarter and her SETI colleagues didn’t want those usual invitees: They wanted Silicon Valley technologists. And Silicon Valley technologists, with their dreamy entrepreneurial visions, require minibars and rooms of their own, with views.

At the last conference, the attendees’ main conclusion was “SETI needs its own telescope,” closely followed by “And perhaps we should figure out how to build it.” Though piggybacking had worked well in SETI’s early decades, to gather and handle the stream of data they expected, searchers would need their own setup and computers hundreds of times faster than those that presently existed. The tech moguls, used to thinking about the big thing after the next big thing, suggested the SETI scientists “make a bet on technology,” specifically on a concept called Moore’s Law. This law, which is just an observation of what happens in the real world, states that computers double in power every two years. The computing power doesn’t exist today, but it will be there tomorrow, when you need it. And it will be cheap(ish). It was a Silicon Valley idea, new to the scientists, and it felt radical back then, when everyone still had dial-up AOL and videos didn’t go viral because they took too long to load.

With the future’s unimaginably shiny computers in mind, Tarter and her colleagues made a plan for their SETI-specific observatory: a bunch of small antennas—350 of them—that worked together. If you point multiple antennas at the same thing at the same time, you can merge their views to make a single superior image, as sharp as if it came from a single telescope 3,000 feet wide. The team estimated the observatory’s cost at $25 million. The SETI Institute just needed to find the money and a place to plop the antennas. Long-established collaborations with the University of California at Berkeley made the location easy: Berkeley’s Hat Creek facility. The institute would largely build it, Berkeley would largely operate it, and the two would split the observation time 50/50.

Luckily, Tarter knew someone who had $25 million to spare and a soft spot for SETI. Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft, had donated to a SETI project called Phoenix in the 1990s. She asked him if he would again like to support and save SETI. While the team awaited Allen’s response, they began building a prototype array: a collection of practice antennas on which they could test each new part before transplanting it into the real-world antennas. The prototype lived in a horse paddock outside an empty barn in Lafayette, California, with the control center in the former tack room.

The night before the prototype’s dedication ceremony, Tarter stayed up late, working and refreshing her email. She hoped Allen would respond with a yes, so they could announce his endorsement at the ceremony. But the inbox disappointed, and she eventually headed to bed. Not wanting to wake her husband, she attempted to take off her pantyhose in the dark. But instead of being stealthy, she tumbled over and shattered her elbow. With 13 pieces of titanium and straps embedded in her arm, the newly bionic woman sat through the dedication. “I kept wanting a more heroic story to tell,” she says, and sighs. “Pantyhose.”

A few months later, Allen’s email came: a yes. But the yes was conditional. If the SETI Institute and Berkeley made a list of milestones—proving step by step that they could develop this telescope and its new technology without screwing up—he would support them, in installments. “ ‘We can do that, fine,’ ” Tarter says now, imitating herself back then. “We didn’t know what we were talking about.”

**********

The first search for extraterrestrial intelligence was made in 1960, in Green Bank, West Virginia, when Tarter was still in high school. Astronomer Frank Drake, a young researcher with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, had a bold plan and approval from the Green Bank Observatory’s director. Drake had calculated that the facility’s 85-foot radio telescope could detect extraterrestrial radio broadcasts as weak as the ones humans then transmitted. No one had ever sought out extraterrestrials before, and it was possible they were abundant and talkative, just waiting for us to tune in.

Drake selected two nearby sun-like stars, pointed the telescope at them, and scanned through frequencies much like you do when searching for a radio station. He sat alone in the buzzing control room beneath the telescope dish. As the night sky spun on and he looked up at those two stars, Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani, he wondered whether someone—maybe with two legs and a radar transmitter, or four legs and a broadcaster he couldn’t yet dream of—was looking out from his or her own planet at a tiny dot in the sky: our sun. Over the course of four months, Drake sat in that control room for 115 hours, listening and hoping for signs of that someone. He heard nothing.

Five hundred miles away, a girl named Jill Cornell scrawled diligently away at her homework. Cornell, who later became Jill Tarter, first considered the possibility of alien life while on a family vacation to visit her aunt and uncle on Florida’s Manasota Key. Her father took her for a seaside walk to teach her the constellations. He pointed up at each set of stars, explaining how they seemed to connect into a coherent picture. But they were actually light-years apart, he told her. Standing on the deserted beach, toes knocking against seashells like those she collected and categorized during the day, she considered the idea that those stars might be someone else’s suns. It made sense to her. And on some planet circling one of those stars, some other creature was probably walking along some other coast. That creature could peer up at its sky and see our sun, which would be a part of constellations unrecognizable to us.

While Tarter was becoming an engineer, then a mother, and then an astronomer, SETI was gaining momentum. The modern SETI movement began with Frank Drake’s Green Bank experiment coinciding with the publication of a journal article by astronomers Philip Morrison and Giuseppe Cocconi. Morrison had just finished work on the Manhattan Project when he took a professorship at Cornell University. One spring day in 1959, Cocconi came to his office and struck up a conversation about gamma-rays and how the universe makes them.

“We realized we knew how to make them too,” in particle accelerators, Morrison said in a 1990 interview for the book SETI Pioneers. But gamma-rays require a lot of energy to create. After eliminating other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum for various reasons—no one knew how to create ultraviolet radiation; dust particles in space scatter and absorb visible light—Morrison and Cocconi decided that radio waves represented the most likely form of interstellar communication. In fact, hydrogen atoms—which make up 74 percent of the universe—emit radio waves that are precisely 21 centimeters long. Cocconi and Morrison thought any astronomically competent society would have discovered hydrogen’s radio waves. And any halfway intelligent species would have built instruments specifically to detect those waves.

The two scientists wrote their ideas in a two-page paper titled “Searching for Interstellar Communications,” which appeared in the September 19, 1959 issue of Nature. “The reader may seek to consign these speculations wholly to the domain of science fiction,” they wrote. “We submit, rather, that the forgoing line of argument demonstrates that the presence of interstellar signals is entirely consistent with all we now know, and that if signals are present the means of detecting them is now at hand.”

And then came this famous line, still a SETI rallying cry: “The probability of success is difficult to estimate, but if we never search, the chance of success is zero.”

When Drake performed his first search for intelligent life, a businessman named Barney Oliver was so intrigued by the idea that he jumped on an airplane to visit Green Bank. Oliver, who led research and development at Hewlett-Packard, soon became a SETI advocate, speaking publicly whenever he got the chance. NASA decided to put his voice to use: The agency asked him to chair a committee commissioned to think about “what would be required in hardware, manpower, time, and funding to mount a realistic effort, using present (or near-term future) state-of-the-art techniques, aimed at detecting the existence of extraterrestrial (extrasolar system) intelligent life.” The committee met over the course of 10 weeks, piecing together the specifics of a SETI scientist’s dream telescope.

The document to emerge from the committee, called the Cyclops Report, presents a 250-page elaboration on its own introductory statement: “We now have the technological capability of mounting a search for extraterrestrial intelligent life.” It describes potential signs of such civilizations and a potential detection system—called the Cyclops, specced down to the capacitors—that could pick up a message. The scientists suggested the Cyclops, a telescope composed of many smaller antennas that would together have an area of 100 square kilometers (39 square miles), be built in a modular fashion. They could erect a few antennas and see whether any extraterrestrial broadcasts came through. If not, they would build more antennas, making the telescope bigger and more sensitive to fainter broadcasts. If they still found nothing, they would expand the array even more. But when Congress saw the total price tag (six to 10 billion dollars), they put their hands on their pocketbooks and ran away. Although NASA intended the Cyclops Report to make SETI seem doable, the team accomplished the opposite.

Nevertheless, they had produced a thorough and (strange as it sounds) compelling document that remains relevant 44 years later. Some call the report SETI’s bible.

One day a colleague walked up to Tarter’s desk and plopped down the Cyclops Report. “Read it,” he said.

She didn’t stop for two days. When she finally looked up, red-eyed, she was like a person entering a dream world. She could find the answer to the question that had lived in the back of her mind since childhood, as scientifically as she could probe the plasma interiors of stars.

Are we alone?

“This is the first time in history when we don’t just have to believe or not believe,” she thought. “Instead of just asking the priests and philosophers, we can try to find an answer. This is an old and important question, and I have the opportunity to change how we try to answer it.”

Like any conversion experience, this one made the world make sense. “I just knew I’d found the right place,” she says. “There was a feeling of connectedness. I was doing something that could impact people’s lives profoundly in a short period of time.”

Tarter still gives the Cyclops report to graduate students to teach them how to sift radio signals from outer space static. She’s like a zealous convert, passing along the scripture that first inspired her.

**********

The Cyclops report led Tarter to SETI, when it was still an informal group of astronomers, before she wrote the institute’s founding charter in 1984. The ideas in Cyclops were solidified 30 years later during the SETI 2020 conference, taking form as the Allen Telescope Array—not without difficulty. Fundraising stalled, leading Berkeley to back out of the arrangement in 2012. Even Tarter has exited, in her own way, retiring as SETI’s director later that year so that her salary could be used to allow the SETI team members to keep their jobs. She hasn’t really left, though, and continues to proselytize and raise money for SETI’s work from an endowed position at the institution named for Barney Oliver.

On the morning after stargazing outside her dorm room in March 2014, Tarter emerges at 7:30 a.m. and drives the quarter-mile to the array’s main control building, winding along a one-and-a-half-lane road that doesn’t afford a view until you’re right in front of the telescopes. Although the site once housed a dozen staff, whose dogs kept the place lively, the observatory now has no permanent astronomers. In the lobby hangs a sign showing the array of antennas: “30 down, 320 to go.” Over the “30,” someone has stuck a Post-it note that says “42.” The array, in 2017, still has only those 42 dishes, which are sprinkled across Hat Creek Valley as if an angry giant turned a box of them upside down.

“Do you think it would change people’s day-to-day lives if we found a message from extraterrestrials tomorrow?” Tarter asks. “I wonder.”

If humans do ever find out we’re not alone, we will all be tipping our hats to Tarter, for keeping the search alive, for keeping that unanswered question lodged in our brains.

This story is adapted from Making Contact: Jill Tarter and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence by Sarah Scoles, published July 4, 2017 by Pegasus Books.