Circling the Moon

In a new autobiography, an Apollo 15 pilot tells what it was like to fly solo.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/WordenatNASM.jpg)

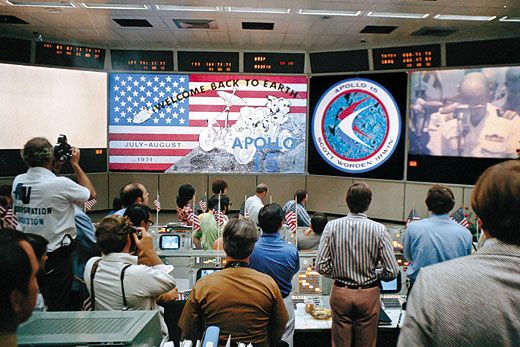

The fourth mission to land men on the moon, Apollo 15 was also the first of Apollo’s extended science missions. After a smooth journey, which began on July 26, 1971, commander Dave Scott and lunar module pilot Jim Irwin stayed on the moon for 66 hours, longer than the two previous lunar landings combined. While Scott and Irwin explored the terrain with Apollo’s first lunar rover, command module pilot Al Worden, orbiting alone in the spacecraft Endeavour, photographed the moon and operated scientific instruments studying its surface. NASA’s then-administrator James Fletcher compared Apollo 15’s scientific return with discoveries Charles Darwin made on his five-year around-the-world voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, but the mission was marred by its crew’s bad judgment: The three men had flown postal covers to the moon, signed them, and sold them to a German stamp dealer. After the business arrangement was discovered, NASA management, embarrassed by the scrutiny the agency was receiving, did not fly the men in space again. In his new book, Falling to Earth: An Apollo 15 Astronaut’s Journey to the Moon, Al Worden recalls the pain of the scandal and recounts the unprecedented adventure of his mission. In this excerpt, Worden writes about his rendezvous with Scott and Irwin after three days of orbital solitude and describes making the first extravehicular activity—EVA—beyond Earth orbit.

—The editors

On my last morning alone around the moon, I woke to a breezy blast of mariachi trumpets. With the serene lunar surface gliding by below me, Herb Alpert’s “Tijuana Taxi” was about the strangest music mission control could pipe up over the radio. But still, it got me awake.

On the lunar surface, Dave and Jim suited up for their final moonwalk before they began preparations to lift off and rejoin me. We all had a busy day ahead. Ed Mitchell, the lunar module expert, was back as CapCom for this critical time. He read up a blizzard of numbers to me, telling me where and when I would need to rendezvous with my moving target.

Later in the day, mission control gave Dave clearance to lift off from the moon. On Hadley plain, Falcon’s engine lit, hurling the spacecraft upward. It quickly pitched over, and zipped along the rille on the curving path needed to reach me.

As Dave and Jim rose in the Falcon, I turned on the cassette player. We were an all-Air Force crew, so I figured it would be fun to play the U.S. Air Force anthem to mission control to provide a stirring background. Bad move. My radio signal was heard not only on Earth: For some reason, mission control also patched it through to the Falcon. Dave and Jim, intently focused on their checklists, now had distracting music in their ears. The ground didn’t tell me; perhaps they didn’t realize what they had done themselves until later.

Had something gone wrong with Falcon at that moment, the music could have been a dangerous diversion. Fortunately, everything went according to plan, and Dave and Jim zipped into an orbit below and behind me. I’d trained extensively to catch them if Falcon lurched into some other, wilder orbit. But I never needed to. I soon had a good radar lock on them. Guided by Ed Mitchell back on Earth, Dave and I flew our spacecraft ever closer, mirroring each other’s moves. “You got your lights on, Jim?” I radioed, watching for Falcon’s flashing tracking light.

I looked through the sextant and the telescope to try to find them, but sunlight in the scopes made it hard to see anything. Finally, in the corner of my eye, I spotted a flash of light in the telescope. I manually drove the instruments over to that point, and there it was: a very bright light. “I’ve got your lights now, Dave,” I told them.

As Falcon steadily rose to meet me, Dave and Jim gave Endeavour an extensive look-over, while I photographed them in turn. Falcon had left its descent stage on the surface of the moon and was now much smaller than when I had last seen it. Falcon was so light, a pulse of its thrusters rattled the lunar module around. So it was easier for me to dock using Endeavour. I slowly slid toward them, so gently that we barely touched. Then, with a touch of my thrusters, I pushed forward into a hard dock.

The rendezvous and docking had been fast—and perfect. “Good show, Endeavour,” Dave radioed to me. “Welcome home,” I replied. That might seem like an odd choice of words—after all, we were still a quarter of a million miles from Earth. But Endeavour had become my home, and Dave and Jim were returning from a great adventure.

I’d kept our home clean and tidy for them. But now, as I opened the hatches between the spacecraft, I saw two grimy faces. Their spacesuits were dirty, and I could smell the moondust. It was a new, peculiar odor—dry and gunpowdery. I kept the hatch closed as much as possible while we began to transfer equipment, hoping the floating dust would not spread. I was mostly successful, but the creep of dust was unavoidable. Dave and Jim floated long sample tubes of lunar dirt and boxes of moonrocks through the hatch, which I stowed inside Endeavour under the couches.

While busily running scientific experiments, I also stored Falcon’s flight plans and checklists, food, film magazines full of priceless photos, and—less priceless to me—Dave and Jim’s used urine and fecal bags. Of all the things to return from the lunar surface, did we really need their crap?

Finally, Dave and Jim floated into Endeavour. I was elated to see them. But Dave didn’t look happy. In fact, while Jim looked away sheepishly, Dave began to loudly berate me about the distracting tune piped into the Falcon during liftoff. Didn’t I know I had jeopardized the whole mission, he thundered, by playing that darn music?

This wasn’t the reunion I had expected. I could only apologize and explain that I had only radioed it to Houston, with no clue they would patch it back to the Falcon. My explanation seemed to satisfy Dave for the moment. I guess he eventually forgave me, because months later at an awards ceremony with the Air Force Association, Dave bragged about playing the tune.

There wasn’t time for me or Dave to dwell on the argument. We had too much to do. Behind in the timeline, we hustled to close the hatches. On the first attempt, the spacecraft hatch did not seal correctly, possibly due to some lunar dust. After more time-consuming checks, we finally seemed to have the problem solved, and Dave and Jim could remove their helmets and gloves. They had started their day with a demanding moonwalk, and they hadn’t eaten for eight hours. They were ready to stop for a while and grab some food.

Then it was finally time to undock from Falcon. “It’s away clean, Houston,” I reported as the lunar module separated with a bang. The separation had taken longer than planned, so instead of our scheduled rest break, we jumped back into our chores.

Jim and Dave would have worked until they dropped, they were so dedicated to the mission. “We’re still trying to get cleaned up in here and get suits put away and all that sort of stuff,” I told the ground. “It’s awfully cramped quarters, and there’s an awful lot of stuff to move around.” The spacecraft seemed very different now that three of us were crammed in again. “I kind of liked it here by myself,” I added wistfully.

By the time we finished everything on the checklist, we were exhausted. We slept deeply for nine hours. The next morning, we all felt much better. With the three of us scrambling to accomplish tasks, my day seemed much more complicated. I was happy to have Dave and Jim back alive, but I began to miss working alone, when we didn’t all have overlapping tasks.

I had enjoyed my time in orbit. There was so much to see that I never grew bored. The sunlit part of the moon shifted as the days went by, so there were always new places to view. I could have happily spent a few more days there—the same feeling I get at the end of a great vacation. But it was time to go home.

Two days after Dave and Jim had rejoined me in Endeavour, I fired the main engine to propel us away from the moon. I could feel the steady acceleration as it burned for over two minutes. I warily watched the gauges that told me our engine was burning smoothly, speeding us on the curved pathway out of lunar orbit.

I settled in for our three-day coast back to Earth. Mission control signed off, reminding us that “our ever-watchful eye will be on you while you sleep.”

When I woke the next morning, I had to carry out some critical navigation. We had one shot to get back home, and I wanted to be on course from the beginning. While Houston kept an eye on us to make sure we didn’t stray out of a general path of certainty, I hoped to prove it was possible to navigate to and from the moon without their help. I was aiming for a narrow sliver of horizon on a planet tens of thousands of miles away, and there was no margin for error. This far from Earth, the tiniest changes in direction could result in huge errors once we had traveled the remaining distance in our voyage.

I used my sextant and measured the angle between Earth’s horizon and my preselected stars. However, I also had to choose the right place on the horizon. Our planet is about 8,000 miles across, and the horizon is only 50 miles deep. That sounds tiny, and it looked tiny from so far away, but 50 miles was too deep for what I needed to do. I needed more accuracy.

In my training, I had calibrated my eye for a specific part of the atmosphere. Between Earth’s surface and the blackness of space, the atmosphere looked like narrow bands of colors, mostly subtly different reds, magentas, and blues. On Earth I had experimented in simulations to identify a thin color line I could find consistently. I looked for a particular light blue within the atmosphere, and this reduced the 50-mile depth to a much smaller path as we left the moon. It worked even better than it had in the simulators: We stayed firmly on track.

We were still much closer to the moon than to Earth, but because our planet is so much larger, its gravity pulled on us more. We were now truly falling to Earth. It meant nothing to us in the spacecraft—there was no physical sensation of our incredible speed as we shot through the black void.

It was time for the three of us to float back into our spacesuits and help each other zip up before I went out for my EVA to retrieve film from cameras in the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay. “You have a go for depress,” mission control told us. We slowly began to let the oxygen out of the cabin through a special valve in the hatch. Everything in the airless spacecraft looked the same, but I knew now that if I took off my helmet, I would die.

“We’re getting ready to open the hatch,” Dave reported. “Okay. Unlatch.”

“The hatch is open,” I announced. I poked my head outside and carefully mounted a 16-mm movie camera on the hatch to film my spacewalk. Then, grabbing the nearest handrail, I soundlessly floated outside.

I paused a moment and waited for Jim to poke his head and shoulders out of the hatchway behind me. He would stay there to keep an eye on me while I made my way down the side of the spacecraft. Other than our service module glinting in the sunlight, it looked really black out there. I looked down the length of the SIM bay. “You ready, Jim?” I asked. “I’ll work my way down.”

After 11 days in space, I was accustomed to weightlessness. With one hand on a handrail, I could turn my body with my wrist. The SIM bay was slightly to the left of the hatch, so I first needed to swing across the face of Endeavour. I let my legs float up, swung around, and worked my way down the side of the spacecraft, hand over hand, never using my feet.

I floated over the mapping camera, then rotated myself on the handrail, placing my feet in special restraints. I hadn’t really had a sense of where I was until this moment. Standing upright on the side of the spacecraft, attached only by my feet and the umbilical that loosely snaked back to the spacecraft hatch, I had a fleeting sense of being deep under the ocean, in the dark, next to an enormous white whale. The sun was at a low angle behind me, so every bump on the outside of the service module cast a deep shadow. I didn’t dare look toward the sun, knowing it would be blindingly bright. In the other direction, and all around me, there was—nothing. It’s a sensation impossible to experience unless you float tens of thousands of miles from the nearest planet. This wasn’t deep dark water, or night sky, or any other wide open space that I could comprehend. The blackness defied understanding, because it stretched away from me for billions of miles.

But there wasn’t time to ponder it too much. I had work to do. I pulled the cover off the panoramic camera, released the film cassette, and tethered myself to it. Jim waited for me at the hatch. “Would you like to get hold of it?” I asked with a laugh as I passed him the film. Jim tethered it inside and released the tether attaching me to it. While Dave stowed the panoramic camera film deeper in the cabin, I floated back down the side of the spacecraft. “Beautiful job, Al baby!” Karl Henize radioed from Earth. “Remember, there is no hurry up there at all.”

“Roger, Karl,” I replied as I grabbed the handrail again. “I’m enjoying it!”

I floated back down the SIM bay, much faster this time. It was time to remove the mapping camera film cassette and bring that back inside. This time the cover didn’t cooperate, and I had to twist and pull hard three or four times before it came away. I pulled the mapping camera film out and floated it back over to Jim, who grabbed the film and unhooked the tether attaching it to me. As we did this, I saw one of the most amazing sights of my life. Jim was perfectly framed by the enormous moon right behind him. It looked as big as the spacecraft, and was dramatically lit by the sun. It could have been the most famous photo in the space program, if I’d been allowed to take a camera out of the spacecraft.

I’d argued for carrying one on my EVA, but the mission planners had worried I’d be busy enough. Now I really wished I’d had one. Well, if I didn’t have a camera, I could at least take a look at where I was. After all, 12 people would walk on the moon during Apollo, but only three would make a deep-space EVA. I would forever be the first, and to this day I hold the record for floating in space farther away from Earth than any other human.

I realized I had a unique viewpoint: I could see the entire moon if I looked in one direction. Turning my head, I could see the entire Earth. The perspective is impossible to have on Earth or on the moon. I had to be far enough away from both.

It was time to float back inside.

Right away, I wished I had spent more time out there just looking around. We had plenty of time. Those film canisters with their priceless images were now safely inside the spacecraft. But I could have soaked in the scene a little more, just for myself.

If I couldn’t take photos outside myself—and Jim had not taken any stills of me either—I knew that at least the 16-mm movie camera should have picked up some spectacular images. But I was wrong. That camera, we learned later, had jammed. It had captured only one frame, showing me floating away.

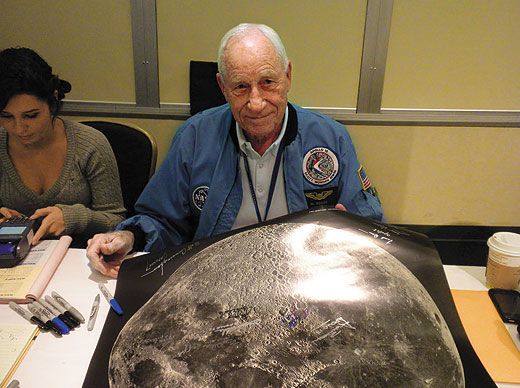

After retiring from NASA, Al Worden worked in private industry before becoming chair of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Francis French is director of education at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.