Fields of Dreams

Will starry-eyed entrepreneurs transform today’s wide-open spaces into tomorrow’s spaceports?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/spaceport_388-may07.jpg)

An epidemic is creeping across the face of the Earth, one that has nothing to do with bird flu, West Nile, or any other microbe in the news, but rather with a disorder that appears to affect the judgment of those afflicted and magnify their ambitions. It’s a uniquely 21st century technological manifestation known as…The Spaceport. Infected with enthusiasm for the new businesses promising to launch masses of humanity into space—Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, for example, has signed up as many as 1,000 passengers for an up-and-back trip—people have suggested building spaceports in places like Upham, New Mexico; Burns Flat, Oklahoma; Van Horn, Texas; Sheboygan, Wisconsin; Columbus, Ohio; and in Singapore, Sweden, Nova Scotia, and Australia.

The forces behind spaceport fever include national, state, and local governments, crown princes, private investors, dot-com billionaires, regular billionaires, aerospace engineers, test pilots, former astronauts, rocket hobbyists, and space cadets of every stripe. All seem to believe that spaceports will be the hot new industry, the next biotech, a completely novel sector of commerce that will produce tall geysers of cold cash and bring jobs, rocket paparazzi, and throngs of deep-pocketed tourists, spectators, and assorted space-niks swarming into the spaceport’s neighborhood. In a scrubby patch of southern New Mexico, for example, a spaceport—Spaceport America—is poised to bring economic salvation to a state that ranks 39th in gross state product.

“Potentially it’s 6,000 jobs,” said New Mexico governor (and now presidential candidate) Bill Richardson last year. “The potential for tourism, for jobs, for new technologies moving into New Mexico is huge.”

It was Richardson himself who was responsible for bringing Virgin Galactic to the state as Spaceport America’s anchor tenant—a feat akin to getting Microsoft to move to Santa Fe, perhaps, except for the minor detail that Virgin Galactic had, at that point, no operational spacecraft in the stable and wouldn’t for some time.

Jerry Larson, president of UP (pronounced up!) Aerospace, another Spaceport America tenant, is also bullish on the spaceport’s future. “There’s this huge market waiting there,” Larson told the Rocky Mountain News last September. “It’s a multibillion-dollar industry waiting to be birthed.”

Admittedly, in the case of New Mexico’s spaceport, a few skeptics were lurking in the wings, people whose somewhat more jaundiced visions were not of spaceports but of space pork. In 2005, the New Mexico legislature appropriated $100 million of the estimated $225 million required for spaceport construction, but state senator John Grubesic wasn’t having any of it. “This is your classic Old West story of your snake-oil salesman who comes to the dying town promising to revitalize it,” he said in the San Francisco Chronicle. “Unfortunately, people have bought it, hook, line, and sinker.”

(The “dying town” in this case could well be Truth or Consequences [née Hot Springs], about 30 miles west of the spaceport, population 7,289. That this gritty little village, composed mainly of gas stations, Mexican restaurants, saloons, Mexican restaurants, laundromats, and Mexican restaurants, could use some major revitalization was beyond doubt.)

But for all the P.T. Barnum hucksterism around it, it’s not as if the spaceport-to-riches scenario were built on nothing but dreams. On October 4, 2004, Burt Rutan’s SpaceShipOne won the $10 million Ansari X Prize, thereby demonstrating that private companies could launch humans into space. The week before the winning flight, Rutan and Richard Branson announced a deal whereby Rutan would license the SpaceShipOne technology to Branson for a new company, Virgin Galactic, that would take paying passengers on flights into space—to an altitude of 60 miles. A spate of other companies immediately announced similar plans but without proven technology to back them up (see “Go Ballistic!” Feb./Mar. 2006).

What did back them up was a market study, issued in October 2002 by the Futron Corporation, a consulting firm located in Bethesda, Maryland. In a 50-page report entitled “Space Tourism Market Study: Suborbital Space Travel,” the company claimed to be providing an objective assessment of an unknown and unproven market. Futron had commissioned Zogby International, a polling firm, to survey 450 well-off individuals in an effort to gauge their willingness to pay handsome fees for a space experience. The survey considered factors such as income levels, vacation and leisure spending, physical fitness, perception of the riskiness of traveling into space, willingness to undergo a week of training and to experience zero-G flight, and so on. Zogby asked whether the chief appeal of a spaceflight was the view of Earth from space, the acceleration of a rocket launch, or something else. The company even fine-tuned the results by adjusting for those whose desire to fly into space was tied up with being a pioneer, one of the first to go.

The Futron study’s conclusion was that by 2021, some 15,700 passengers would be flying into suborbital space per year, generating total annual revenues of $786 million. A separate study of orbital flight demand concluded that in the same time period, up to 60 passengers would be spending $300 million per year, for total revenues of almost $1.1 billion annually. That was not quite the “multibillion-dollar industry” spaceport boosters had forecast, but still, it was big money.

But then last August 2006, Futron issued another report: “Suborbital Space Tourism Demand Revisited.” The new study’s conclusion was slightly sobering: Despite the fact that SpaceShipOne had won the X Prize in the interim, the projected demand for such flights had actually declined. The annual passenger load predicted by 2021 had fallen from the original estimate of 15,700 to 13,000, while anticipated revenues fell from $786 million to $676 million. The price of a suborbital spaceflight, by contrast, had risen from the original figure of $100,000 to $200,000, which happened to be exactly the sum that Virgin Galactic was then quoting for a flight aboard SpaceShipTwo.

Futron theorized that the weakening of projected demand was due to two main factors. One was the doubling of ticket prices; the other was something that had plagued space ventures from the very beginning: delays. The original 2002 study had assumed that commercial suborbital flight would begin in 2006. But 2006 had come and had almost gone, and not a single manned commercial flight had been made, nor had any of the required space vehicles rolled out of the factory.

In the end, there was no getting around the fact that even though they were based on polls and were the product of intelligent analysis, all of these prophecies fell into the realm of sheer theory. What an interviewee will say in a telephone call and what the same person would actually do when faced with the real thing are two entirely separate matters. The people involved were not spending any folding money or putting their lives on the line; they were merely taking part in a survey.

The glib auguries of a “multibillon-dollar industry,” therefore, were pretty much wishful thinking based on guesswork, a phenomenon otherwise known as hype. Sooner or later the reality of the situation will have to be faced.

If we define a spaceport as a site dedicated to launching rockets that can carry tourists into space for private profit, the blunt fact is: There are no spaceports. There are military and federal rocket-launch complexes that have been converted or expanded for commercial uses (see “Payloads Other Than People,” p. 67). There is the Kodiak Launch Complex in Alaska, which has the dual distinction of being the first licensed launch site not co-located with a federal facility and the first U.S. launch site built since the 1960s. But as for spaceports—as defined, there are no such animals in the jungle.

The Oklahoma Spaceport, for example, is a former U.S. Air Force facility (the Clinton-Sherman Air Force Base) that during the 1950s was home to Strategic Air Command B-52s. Today the field consists of a 13,500-foot runway, a couple of abandoned-looking buildings, a control tower, and the most crucial item of all, an on-site golf course. (Didn’t Al Shepard hit a golf ball on the moon?) Rocketplane, the Oklahoma City commercial spaceflight firm, was to be the anchor tenant. But last June, when the Oklahoma Space Industry Development Authority requested a $2 million appropriation for infrastructure upgrades, the state legislature refused. (“We’re considering what to do about that,” said a Rocketplane spokesperson last October.)

Spaceport Washington is an ember from the previous wildfire of space optimism, ignited in 1996 by VentureStar, a proposed Lockheed Martin launch vehicle that was to dramatically lower the cost of getting stuff into orbit. The wedge-shaped, single-stage VentureStar was to launch vertically from Edwards Air Force Base in California and land horizontally, space shuttle-like, on a very long runway. Washington’s Grant County International Airport with its 13,452-foot runway was one of several western sites that fit the bill.

The cancellation of the VentureStar program in 2001 did not dampen the state’s zeal nor that of Aero-Space Port International, a real estate development group, for opening a spaceport in Washington. ASPI corporate counsel Kim Foster says, “Because of our legacy with the Boeing company, Washington state is proactive when it comes to space.” Despite the airport’s wide-open spaces (a feature it shares with many proposed spaceports), no company has indicated enough interest to get the state to apply for a Federal Aviation Administration license to operate a launch site.

One potential spaceport operator who has applied to the FAA is Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos. His company Blue Origin launched a rocket (which reached a height of 255 feet) from a site in west Texas last November, but there’s no spaceport there yet.

Even the Mojave Spaceport (a.k.a. the Mojave Airport and Civilian Aerospace Test Center), notwithstanding its having been the site of the only successful manned private spaceflights in history, and having been licensed in 2004 by the FAA as a spaceport, always had been, and thereafter continued to function as, an airport, identified as MHV in official FAA publications, Notices to Airmen, airport directories, instrument approach and departure plates, navigational charts, and so on.

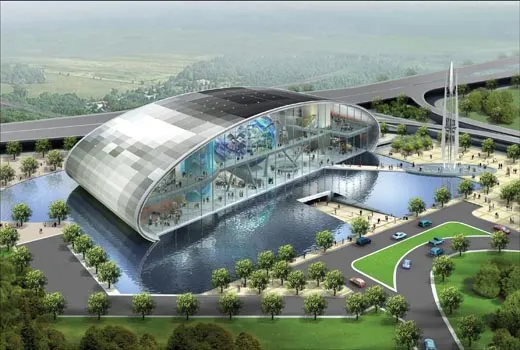

The fabled spaceports of Dubai, Singapore, and elsewhere exist primarily in the form of Web sites and/or misty artist’s conceptions.

Against all this, the only launch site that has remotely approximated the concept of an operational spaceport for private, as opposed to government, launch vehicles and payloads was a tiny patch of concrete in the New Mexico desert across the San Andres Mountains from the White Sands Missile Range command center. Here, at Spaceport America, on September 25, 2006, UP Aerospace (UPA), a private rocket company based in Connecticut, attempted its first commercial launch. Because Spaceport America does not yet have its spaceport license, UP Aerospace obtained FAA approval to launch from temporary facilities.

The story began the night before, at the “Mission Safety Briefing” held at the Hilton Las Cruces, which, even though it was some 100 miles from the launch site, was serving as UPA mission headquarters. The mood was giddy. Not once at the safety briefing was the word “safety” mentioned. Mostly, the event gave UPA the opportunity to introduce its launch crew and allowed the company’s college, high school, and elementary school clients to describe their science payloads. Colleges in New Mexico, Connecticut, and Colorado were flying experiment packages, such as a three-axis accelerometer, a magnetometer, and a Geiger counter, among other things. Two fifth-grade students, Alison and Lydia from Farnsworth Aerospace Elementary School in St. Paul, Minnesota, had placed three wristwatches—two analog and one digital—aboard to find out which type would better survive microgravity, reentry, landing, and the 13 Gs of liftoff. In all, there were about 40 payloads inside the SpaceLoft XL-1 rocket, a 20-foot-long, 10-inch-wide craft that would be shot into the blue the following day.

Next morning, members of the media, UPA clients, and guests left the hotel at about 3:30 a.m. for the 100-mile drive to the VIP viewing area, which was about three miles from the launch site. The site itself consisted of little more than a concrete launch pad, the launcher rail (called “T Rex”), and a couple of modular structures functioning as the vehicle’s final assembly building and the launch control center.

Arriving at the viewing area in temperatures just above freezing, launch-goers could see faint traces of dawn behind the San Andres range to the east. Launch time was set for 7:30 a.m. Well before then, Rick Homans, New Mexico’s state secretary for economic development who was acting as master of ceremonies, announced over the PA system that the rocket’s transponder wasn’t working. The transponder was essential for recovering the payload: The vehicle had no guidance system; the rocket, aimed a few degrees from vertical, would be launched ballistically, like a cannonball. The plan was for the rocket to reach Mach 5 in 13 seconds, then coast to its target altitude of 70 miles. At that point, the nosecone would separate from the body of the rocket, parachutes would deploy, and both sections would come down gently within a 20-mile-wide area somewhere in the White Sands Missile Range, which would track the thing by radar. The entire flight was to take approximately 13 minutes. However, fixing the transponder required the removal and replacement of 72 bolts.

Hours later the transponder is working. During the delay, UPA’s commercial clients take the chance to describe their payloads. A Las Cruces company, Heavenly Journeys, is flying the ashes of a veterinarian whose widow is attending the launch. Another firm is flying ingredients for an energy drink. There are other oddments—a plastic bag of 12 Cheerios, for one—all tucked away inside pizza-shaped payload containers.

As the final countdown nears, launch time shifts back and forth from 2:05 to 2:15 with no explanation. Reuters is here, ABC, Fox News, National Public Radio, Associated Press, a French film crew, local reporters—there’s probably more media here than customers—millions of cameras on tripods to record the flight that is to inaugurate the revolutionary, paradigm-shifting, historic era of public access to space.

At last the rocket gets away. Watching it is a thrilling experience: a point of dazzling white light followed by a contrail straight as a knife edge and as bright as if it were illuminated from the inside. Then, suddenly, the contrail becomes a corkscrew, and I’m immediately reminded of the Challenger disaster. In a few more seconds, although everybody is still looking skyward at the twisting track of rocket exhaust, it’s announced over the PA system that, barely three minutes into the flight, the rocket is back on the ground.

Back on the ground?

An Associated Press story filed five days later described the SpaceLoft XL rocket as “the first launched from a commercial spaceport in New Mexico—and the first to crash.” That was not in the least surprising. At the post-flight briefing, held the same night back at the Hilton, Lonnie Sumpter, executive director of the New Mexico Spaceport Authority, who had also acted as the flight’s launch director, said: “Forty-six percent of first launches suffer a failure.”

Sumpter, who died in February after a brief illness, was a commanding presence. A mechanical engineer who had spent 16 years at White Sands flight testing missile systems, he knew whereof he spoke. Still, a 46 percent failure rate was scarcely a comforting thought in view of the question on some people’s minds, namely: What if this had been a manned flight?

The crash of the UPA rocket was a cautionary tale. It is wrong to think that rocket flight is like aircraft flight, only a little higher and a little faster. Unlike atmospheric aircraft, a spacefaring rocket undergoes extremes of acceleration and deceleration, plus vibration and buffeting, reentry heat, and other space-specific influences. All these factors combine to make spaceflight a classic case of “sensitive dependence upon initial conditions,” meaning that the smallest mechanical, software, or other imperfection—such as the brittle O-ring that doomed Challenger —can have momentous outcomes.

Such a defect was catastrophic to UPA’s SpaceLoft XL-1 and to most of its scientific payloads. The University of Colorado’s electronics package had been reduced to a charred, deformed, and melted husk. Central Connecticut State University’s package, broken into pieces, had returned no data. Alison and Lydia’s analog watches, despite having been carefully encased in bubble wrap, had stopped at 2:17. The digital watch was defunct, its face blank.

In January 2007, the company announced that the crash had been caused by a defective tailfin assembly, which engineers have since redesigned. And there was a silver lining: Worldwide coverage of the first launch had produced so much publicity that UPA’s next two flights were fully booked.

UP Aerospace will not make or break the New Mexico spaceport; Virgin Galactic will do that. But in the aftermath of the UPA crash, some of the major players in space tourism were taking a second look at how the crash (or a series of crashes) of a manned private rocket, plus a raft of huge liability claims, would affect the industry. Last October, some of the high priests of space tourism met in Las Cruces for the International Symposium for Personal Spaceflight. NewScientist.com, which covered the meeting, reported a few of their comments:

“Space is risky, and safety will be one of the defining factors in the development of space tourism for the first few years,” said Eric Anderson, president and CEO of Space Adventures, the Arlington, Virginia firm that has arranged five visits to the International Space Station for wealthy clients, including the latest, Charles Simonyi, the creator of Microsoft Word.

“No matter how much energy we put into safety, there is a chance of an accident,” said Alex Tai, chief operating officer of Virgin Galactic.

“What happens if someone in the industry crashes and burns? It could affect everyone,” said Kirby Ikin, of Asia Pacific Aerospace Consultants.

Even Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin, the second man on the moon, said that he would decline the offer of a private rocket flight. “I don’t need that publicity anymore and I don’t need that risk.”

And who could blame him? Accidents have eliminated not only individual aircraft types—such as the de Havilland Comet, three of which broke up in the air between May 1953 and April 1954—but entire modes of transportation. The Hindenberg disaster of 1937 ended travel by Zeppelin, and the crash of the Concorde in 2000 effectively terminated journeys by supersonic transport. The up-and-down flight planned by Virgin Galactic—a voyage from nowhere to nowhere and back again—does not even have the advantage of being a mode of transportation: It is, merely, entertainment. That may be the saving grace.

In the end, whether spaceports will be a bubble or a business will be determined by the reliability of the spacecraft involved and by the space tourists’ ability to tolerate risk. Plenty of people engage in dangerous sports such as mountain climbing, untethered rock climbing, and BASE jumping, an extreme hobby in which a person jumps from a Building, Antenna, Span (such as a bridge), or point of Earth (such as a cliff), and opens a parachute on the way down. BASE jumping has had its share of fatalities (the latest occurred last October, when an experienced BASE jumper died moments after leaping from New River Gorge Bridge in West Virginia), but the sport, and the deaths, continue. Maybe the same will hold true of private manned rocket flights.

So are spaceports the wave of the future, the next big growth industry? The only safe, sane, and sensible answer is: Nobody knows. As physicist Niels Bohr used to say: “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.”