Lunar Landers That Never Were

The road to the moon was paved with good intentions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Langley-631-feb08.jpg)

So NASA has a new name for its future moon lander—Altair—and brand new artwork showing the spindly-legged craft that will one day carry four astronauts to the moon’s surface. What’s more, the agency says it plans to start building test hardware next year.

Great news. Just don’t count on it. With Altair’s landing still many years away (the target date is 2020), NASA and its industry contractors are almost sure to change their minds umpteen times before finalizing any designs for moon vehicles.

The history of the Apollo program is instructive. Before NASA and its industry contractors settled on a final design for the Grumman-built Lunar Module, they took many a wrong turn; the LM’s look kept changing even after Neil Armstrong’s giant leap for mankind in July 1969.

All the ingenious, would-be landers that never got off the drawing board, let alone the planet, are now fully documented in the pages of Robert Godwin, publisher of Apogee Books.

Godwin offers pictures and short histories for more than 80 lunar lander concepts of the 1950s and early 1960s, along with more than 80 lunar rovers and mobile labs and more than 50 lunar flying vehicles. When he couldn’t find contemporary artwork or photos, he rendered his own using modern computer graphics. The result is a comprehensive encyclopedia of all the moon missions that never flew. And aren’t we sorry they didn’t?

Below are a few of our favorites, with text excerpted from the book. Click on the thumbnail photos above to see full-size photos, numbered from left to right. And don’t laugh. Altair might end up in here some day.

All photos and the following text ©2007 by Robert Godwin, from The Lunar Exploration Scrapbook, Apogee Books, 2007.

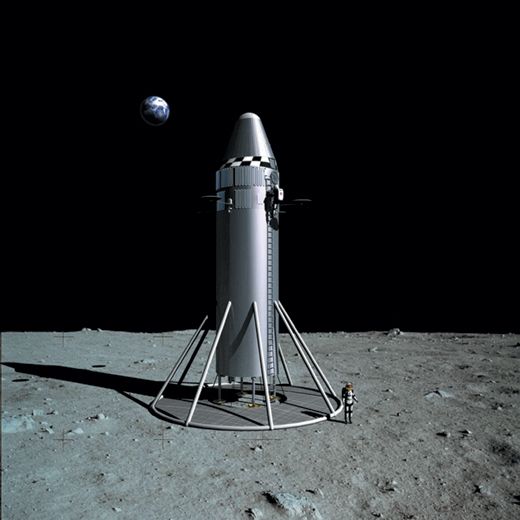

1. Large image: Langley Landers (1961)

In August of 1961, engineer John Houbolt gave one of many presentations to the Space Task Group [at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, where he worked]. In attendance was Jim Chamberlin, the brilliant designer of the Canadian Avro Arrow fighter. Chamberlin was heading up what would become Project Gemini, and he had already begun to think about using the new larger "Advanced Mercury," as Gemini was called at the time, to do more than just fly in low Earth orbit. Chamberlin wanted to use Gemini to go to the moon, and he would make that exact suggestion later that year. His team’s design for an accompanying lunar lander was similar to one proposed earlier in the year by the Langley staff. It was basically nothing more than a platform placed on top of a rocket engine, on which an intrepid astronaut would stand, surrounded by fuel tanks.

2. Martin Model 410 Lunar Direct (1961)

Within weeks of President John F. Kennedy’s May 15, 1961, announcement that the United States would land a man on the moon, the Martin company produced a staggering 9000-page study with their solutions to lunar flight. Martin produced at least three totally different designs for a lunar descent stage. Surely the most bizarre of these three designs involved a type of inflatable landing gear.

3. Lunar Gemini (1962)

All three of the proposed versions of Lunar Gemini [a plan to use NASA’s mid-60s Gemini spacecraft for the moon landings] had the fundamental drawback of not allowing the astronaut an unobstructed view of the lunar surface during descent. Creative solutions were required. Three different canopy configurations were proposed for landing, including an open hatch with a zippered canopy, a titanium reinforced bubble, or simply a rear-view mirror. The first of the three would allow for the least redesign work but would require the pilot to lean out of the hatch while flying down to the moon. In the rendering here you see the version that replaced the left hatch with a titanium and glass bubble that allowed the pilot to kneel and look down towards the moon while flying the vehicle.

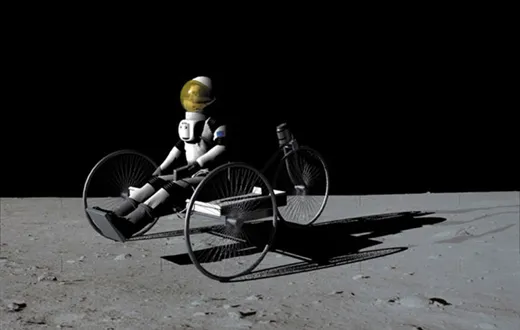

4. Chrysler MLAV (1963)

Undoubtedly one of the strangest vehicles to come out of the early Apollo studies was the Chrysler Corporation’s Manned Lunar Auxiliary Vehicle—a nuclear tricycle. The MLAV had a cargo tray 23 inches by 41 inches in size, and could be operated with a hand controller either by a riding astronaut or by remote control. A full size prototype was built and tested by Chrysler. The power source for this machine was to have been a SNAP 91 radioisotope thermoelectric generator, although it is not clear where this device would have been located. Other refinements would have included a television camera. The three wheels were tested with brushless DC motors which provided enough torque for its projected mission. Its primary use was as a "pack animal," but it could be used to carry one astronaut if required. The entire vehicle could be folded up flat.

5. U.S. Geological Survey LMs (1964-1967)

One of the interesting offshoots of the Apollo training program was the deployment of what must surely be the strangest pair of Lunar Modules ever built. One was commissioned specifically by NASA for the U.S. Geological Survey scientific team that trained the lunar astronauts, and built to scale by Grumman in the summer of 1964. It was made entirely of plywood and its main mode of propulsion was a flatbed truck. Another cloth-covered LM [shown here] was little more than a LM-shaped tent and was deployed at the top of a ladder. It was designed purely to give the astronauts [John Young (top) and Charles Duke are picured] a basic feel for working with a home base during field training.