Star City at 50

Change comes to the place where spaceflight was born.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/FM-2011-star-city-at-50-1-FLASH.jpg)

Deep in a birch forest 25 miles northeast of Moscow’s Red Square is a collection of apartment blocks and gray buildings, some rather oddly shaped, that gives the impression more of a campus than of a town. On many days the roar of jets from a nearby airfield shatters the silence, but otherwise the place is quiet, remote, apparently serene—a Russian gated community.

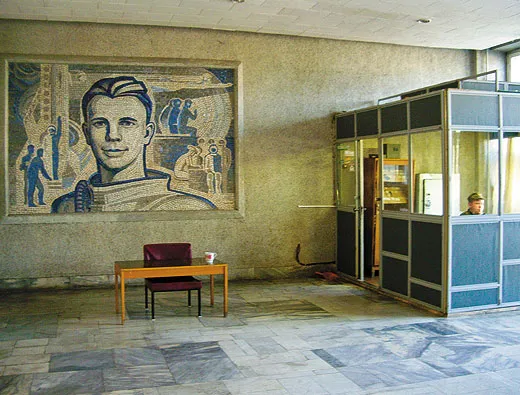

Known as the Federal Budget State Research Center and Cosmonaut Training Center, the complex bears the name of a national hero, Yuri Gagarin. NASA calls it the GCTC, short for Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. More popularly, and slightly inaccurately, it goes by the name of Star City (a better translation is “Starry Town”), and at the age of 50, it is the world’s oldest facility dedicated to the business of training humans to fly, work, and live in space.

Over its lifetime, the center has trained more than 120 crews for launches on Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz spacecraft, or for trips to Mir and the International Space Station on the U.S. space shuttle. Most of the trainees have been citizens of the Soviet Union and Russia, but graduates of the center include more than 140 Americans, Europeans and Japanese, half a dozen Chinese astronauts, and all the world’s space tourists, from U.S. millionaires Dennis Tito and two-time flier Charles Simonyi to Canada’s Guy Laliberté and Iranian-born Anousheh Ansari. Center officials estimate that 400-plus people have studied in its classrooms and trained in its simulators.

Today the center is facing challenges unlike any it has ever known. Its major buildings, constructed in the 1960s, are crumbling under the dual assaults of weather and age, and for the first time in its history, the facility is under new management. In July 2009, control passed from the Russian air force to Roskosmos, the country’s civilian space agency. The center’s director, veteran military cosmonaut Vasily Tsibliyev, was retired.

His replacement? Civilian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, at 52 a veteran of six spaceflights and two tours on the International Space Station, the first cosmonaut to fly on the shuttle, and holder of the world record for time spent in space (803 days). Krikalev is generally considered one of the most capable and popular space travelers in the world. (He even flew—and remains friends with—Charles Bolden, the current NASA administrator.) But will skills learned in space prepare him for the job of re-energizing Star City as it enters its second half-century?

THE SOVIET MINISTRY OF DEFENSE order creating a “Cosmonaut Training Center”—Military Unit 26266—came down on January 11, 1960. The center, officially created as part of the Soviet aerospace medical establishment, was first directed by flight surgeon Yevgeny Karpov. A site was chosen not far from the Chkalov Air Base, home of the USSR’s military flight test center, and within reach of both the Red Banner Air Force Academy in Monino and the Korolev Design Bureau in Kaliningrad, where the Vostok spacecraft that carried the first cosmonauts to orbit was built. When Karpov, his staff, and the original cosmonauts—a group that included Gagarin, Gherman Titov, and Alexei Leonov—moved to the location in 1960, they took up just one building.

Over the next decade, Star City grew in size and budget, expanding to a staff of 600, with more than 60 cosmonauts. The team worked on plans for lunar landing missions as well as manned military projects, and got its own aircraft support unit, the 70th Special Destination Wing, based at Chkalov. The center’s directors were air force generals, many of them former cosmonauts. With the abandonment of the lunar program and the scaling back of military efforts in the 1970s, the facility concentrated on training cosmonauts for long-duration space station missions on Salyut and, in the 1980s, Mir.

Star City first opened its doors—grudgingly—to Americans in 1973, when NASA astronauts began training for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. A special residence was built for the Americans on the grounds of the center (the building was later converted into the Profilactorium, a medical center for crews recuperating from long-duration missions. It now houses the NASA director of Russian operations and his team).

NASA has had a permanent presence at Star City since 1994, when astronauts Norm Thagard and Bonnie Dunbar began to train for the first shuttle-Mir mission. Integrating the civilian U.S. team into a closed Russian military center wasn’t easy. Driving onto the grounds for the first time one cold February day in 1994, astronaut Ken Cameron looked at the grim buildings, barbed-wire fences, and armed guards and told his small team, “Well, guys, there’s only a few of us cowboys, and a hell of a lot of Indians.”

Culture shock was a serious problem for the Americans. Recalls astronaut Mike Lopez-Alegria, NASA’s director of operations in Russia from 1996 to 1997: “You couldn’t find a restaurant. The telephone situation was bad. There were no gas stations. Gasoline was sold from trucks that were just pulled up along the road.”

Bert Vis, a Dutch space researcher, co-authored the only published history of the GCTC, Russia’s Cosmonauts: Inside the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center, which came out in 2005. Originally invited to Star City by a cosmonaut pen pal, Vis has made 17 visits, for a week or two each time, since 1991, when the Soviet Union disbanded. In the early days, Vis bunked in his host’s apartments, could not use a computer, and barely had access to a phone. Lately he has been able to book rooms at a hotel, though landline phones are still iffy.

The greatest change since the Soviet breakup has been the way Star City residents react to foreign visitors. At first “people would stare at me,” Vis says. “They were not used to seeing a foreigner there. When they heard me speak English, they would turn their heads and look at who that stranger was.

“There were older military officers who refused to meet with me, thinking that talking to a Westerner would harm their careers,” he adds. “Don’t forget that the old generation owed everything they had to Communism.”

Today, NASA astronauts live at Star City for months at a time, in Western-style cottages. And, Vis says, “The latest groups of cosmonauts are much more open to non-Russians, and don’t see the NASA guys and Europeans as spies who come to steal their technology.”

That may ease cooperation with Americans, but Krikalev also has to contend with other culture gaps and rivalries—among Russians. At the space station’s mission control center in Moscow, the staffers, including the all-powerful flight directors, are employees of the Energiya Corporation, which builds the spacecraft. But the capcoms (capsule communicators, or “glavnis” in Russian), who communicate with the cosmonauts in flight, come from Star City. GCTC doctors handle all the preflight medical care for cosmonauts, and work with them on a daily basis. But during missions, physicians from another organization, the Institute for Medical-Biological Problems, are in charge. According to John McBrine, a NASA veteran of four tours in Russia, “There’s no way the IMBP doctors have the same relationship to the crew the GCTC guys do.”

Another fundamental rift is between the two kinds of cosmonaut: the military pilots in Star City and the civilian engineers like Krikalev, who come from Energiya. The smaller Energiya team lives and works in Moscow, commuting to Star City only when assigned to a specific program. Beginning in 1966, Soviet law required each cosmonaut crew to have a commander from the GCTC, as well as a flight engineer from “the organization that built the vehicle,” meaning Energiya. It would be as if NASA had ordered every Gemini crew to include an engineer from McDonnell aircraft.

For years, both organizations fought for the right to command space missions. “GCTC rightly felt that every spacecraft commander should be one of their pilots,” says McBrine. In some cases, a veteran Energiya engineer had to work under a rookie GCTC commander—not the most harmonious of situations.

Today the training center is part of Roskosmos, which was created only in 1994 to serve as a Russian counterpart of NASA. Headed by Anatoly Perminov, the agency is trying to foster a thriving Russian space industry. It intends to end the country’s reliance on the Baikonur Cosmodrome, located in the independent nation of Kazakhstan. Roskosmos plans to transform a missile base at Svobodny, in the Russian far east, into the Vostochny (“Eastern”) Cosmodrome, and hopes to launch cosmonauts from there by 2018.

Though Roskosmos owns Star City, the agency doesn’t necessarily like the arrangement. According to former cosmonaut Yuri Baturin, “Roskosmos did not plan to absorb GCTC. But the Ministry of Defense specified reductions in armed forces, and simply included GCTC in that.” Apollo-Soyuz astronaut Tom Stafford put it more directly: “The Russian air force couldn’t afford to keep paying the bills. They don’t have an interest in manned spaceflight—they never really did.”

The shift from military to civilian ownership poses a staffing problem for Krikalev. The center was allowed to keep 210 military employees, and another 110 workers were allowed to leave military service and stay in their jobs. But that still leaves dozens of positions unfilled, and many military people stationed in Star City scrambling to find assignments elsewhere.

To hire replacements, Krikalev has to offer salaries competitive with those of private industry, placing extreme pressure on his budget, which needs to be doubled to “keep the center functioning properly.” He plans to recruit directly from Moscow’s best technical schools, Bauman Moscow State Technical University and Moscow Aviation Institute, but says, “I’m not giving up on graduates from military schools.” Also on his wish list are space and missile students from Mozhaisky Academy, in his hometown of Leningrad. He’d like the cosmonaut corps to be larger and more diverse, noting that only one of 34 Russian cosmonauts is a woman.

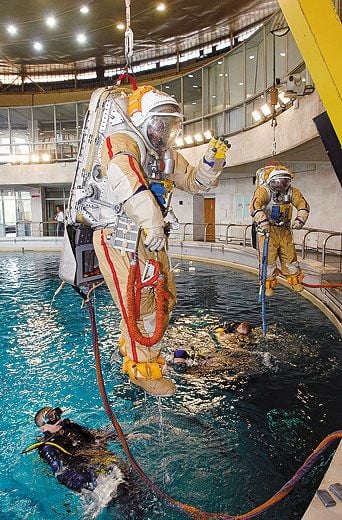

Then there is Star City’s aging infrastructure. Most of the center’s buildings were constructed during the glory days of the 1960s. Some “look like they’ve been shelled,” Krikalev complains. Richard Garriott, the video game entrepreneur who financed his own trip to the space station on the Soyuz flight TMA-13 in October 2008, says, “They have very limited money for exterior work, but always have money for the essentials: simulators, the centrifuge, the hydro-lab.”

Under military control, the training center’s flight support unit, the Seregin Wing, had 16 aircraft, from Aero L-39 training jets to Tupolev Tu-154 transports. These were used by the cosmonauts to maintain pilot proficiency, and for weightlessness training. But in late 2009, the Russian air force disbanded the wing and dispersed the airplanes. “Except for one,” Krikalev notes, “a Tu-154 with glass hatches in its fuselage,” which was formerly used by the Ministry of Defense in NATO’s “Open Skies” program.

Juggling these management problems while continuing to train space station crews has been difficult, says Baturin—“like rebuilding the conveyor belt while you still manufacture the item. Imagine what a car would look like under those circumstances.”

Star City’s main business, of course, is spaceflight training. And the methods developed there over 50 years are often quite different from NASA’s. The GCTC trainers emphasize theoretical classroom work, complete with regular graded exams, while NASA concentrates on practical skills, teaching astronauts to perform specific tasks like operating the station’s robot arm or conducting a spacewalk. “GCTC will test you on the nature of an electronic relay,” says Lopez-Alegria, “but knowing that doesn’t help me operationally. We don’t do systems, we do skill sets.”

In the old days, the GCTC published few manuals; cosmonauts took handwritten notes at lecture sessions. Staffers were reluctant to print and distribute written materials, because they saw the information as proprietary. (In early 2008, South Korean astronaut candidate Ko San was removed from a Soyuz crew assignment for taking workbooks out of Star City without permission. According to one former NASA astronaut, manuals are still officially restricted to the center.)

As a first-time flier, Garriott saw value in the Russian methods, including the emphasis on theory: “At first I wanted to rush through that phase. But eventually I became a big fan of the Russian top-down system.” For example, he says, “I started training, right from zero, with my crew and with the same small team of instructors. Over the weeks and months, these two or three instructors followed every step of my progress: what I got, what I didn’t get, how I responded to every situation. We passed our exams, then flew down to Baikonur, where we were in quarantine for two weeks. We suited up, got out to the pad, got into the Soyuz. And on the radio was one of my instructors! I hadn’t realized that would be the case. But it was so reassuring! I realized, That guy knows me. Back on the ground, after the flight, the crew starts its debrief—and the same instructor is there too.”

This emphasis on personal relationships is one of the reasons the glavnis in Russian mission control are from Star City, not Energiya. NASA has started to move toward a similar model: Many space station capcoms are now members of the training teams, not fellow astronauts. “Both sides have learned from each other,” says McBrine.

STAR CITY IS MORE THAN just a school for space travelers. It also is a company town with a population of 6,000, including retired cosmonauts, training specialists, engineers, and administrative staffers and their families, as well as businessmen, cooks, and schoolteachers. There are baptisms and weddings. Children of cosmonauts have married and raised families here, and a Russian Orthodox church was dedicated last winter—a first for Star City. There are, of late, many funerals.

For 49 years, the military director of the GCTC doubled as the “mayor” of this unique village. But the shift to civilian control brought an election in June 2009. The winner was Nikolai Rybkin, a 63-year-old retired air force colonel who was Star City’s State Security (KGB) representative from 1976 to 2001. Rybkin was a popular figure in Star City because he paid attention to things that mattered to its residents. “He was great about getting a gazebo built and returning the swans to the lake,” says one NASA official who asked to remain anonymous. “I just wish he’d also put more street lights along the roads.”

At the time of his election, Rybkin was in jail, charged with smuggling, and so was unable to take office. In late October 2009, Russian government officials appointed former cosmonaut Alexander Volkov, a Rybkin supporter, to take his place—which speaks to the insular nature of Star City. During the glory days of the 1960s, residents had special access to food and consumer goods, and lived in apartments that were double the standard Soviet size. The price for these privileges was submission to strict military and KGB control. Three cosmonauts from Gagarin’s group were expelled for “violation of training discipline” when one of them started a drunken argument with the local militia. Over the years, others were sent packing for marital discord, embarrassing personal connections (engineer Boris Belousov was discovered to have Ukrainian relatives who had fought on the side of the Germans during World War II), or failing to appreciate the Communist Party (Eduard Kugno openly criticized the organization as “a pack of lickspittles”).

In the old days, it was also risky to criticize Star City management. In 1967 engineer Gennady Kolesnikov, while a candidate for the cosmonaut corps, complained about training methods and was ordered to see the doctors. “I was checked for ailments, and they found 12!” he told Bert Vis. With this “medical disqualification,” he was transferred to a teaching job outside the center.

Star City’s managers often used the medical department as a disciplinary arm, a ruse that veteran cosmonauts knew well. Following his 1965 Voskhod 2 flight, Pavel Belyayev was so suspicious of the center’s doctors that he skipped medical exams for months. Tragically, he developed a bleeding ulcer that turned into peritonitis, which killed him.

Cosmonauts aren’t always exemplars of the healthy lifestyle. Garriott’s backup, Australian entrepreneur Nik Halik, recalls “working out in the gym with cosmonauts, then walking outside to see them puffing cigarettes and drinking vodka.” The darkest side of life at Star City has long been alcoholism. One unnamed veteran cosmonaut says that “90 percent” of the staff of one engineering department drank too heavily. The affliction is most common among the dozens of retired pilots and engineers who were selected for cosmonaut training in the 1960s, moved permanently to Star City, then never made it to the launch pad. But the problem isn’t limited to the unflowns. To this day, visitors can find famous names from Salyut and Mir crews stumbling drunk down icy sidewalks. Halik says he drank so much during his year-plus at Star City that now he “can’t stand the sight or even the thought of vodka.”

Maybe it’s because of the small-town insularity that the 1997 class of nine cosmonaut candidates included three second generation spacemen: Sergei Volkov (son of the new mayor), Roman Romanenko (son of three-time flier Yuri Romanenko), and Alexandr Skvortsov, whose father Alexandr was a cosmonaut candidate in the 1960s. This isn’t necessarily nepotism. Since the 1990s, young Russians have not seen becoming a cosmonaut as the plum opportunity it once was. Interest in the most recent Energiya recruitment in 2005 was so dismal that the company had to go looking for new hires among grad students at Bauman Moscow State Technical University and at Moscow Aviation Institute.

The problem may be a lack of exciting new missions. “Unflown cosmonauts concentrate on future work on [the space station],” Yuri Baturin says. “Those who have completed flights look into the future, and they are often disappointed by the absence of clear plans.” Leroy Chiao, a NASA astronaut who trained in Star City off and on for five years, remembers that cosmonauts and astronauts “didn’t talk about lunar flights, knowing that it was beyond the timeframe of our careers.”

The inbred nature of Star City’s society does have an upside. Richard Garriott—himself the son of an astronaut, Skylab and shuttle veteran Owen Garriott—says, “When I was growing up in the Johnson Space Center community, the astronauts were mostly test pilots—part of an old boy’s network. They played hard, and they played away from home. They rarely appeared at family gatherings, picnics, kids’ baseball games. They had hangouts no one knew about. Star City is completely the opposite.”

Garriott recalls a night in February 2008, shortly after arriving at Star City, when he and Halik entered the Soyuz Café, “a shiny jewel of new construction” that he describes as “half digital, half dacha.” They were immediately invited to a family gathering. “It was for the next ISS crew, and there were babies and grandparents in attendance, in addition to the adults. We sat down. The host welcomed everyone, and every five minutes or so he would ask somebody to stand up and introduce a guest and offer a toast—to the crew, to the future, and so on. I found similar scenes repeated there almost every night for the next year.

“Part of what I experienced was unique—possibly only to Star City. But the vibe you got was ‘Someone you know is in space.’ It’s part of everyday life. It’s continuous. It’s a very meaningful way to deal with this hazardous way of life.”

Rather than resenting the foreign spaceflight participants, says Garriott, the residents of Star City have welcomed them. Part of it is practical: “The Russians love the idea of foreigners buying seats on their vehicles. Not only does it offset the cost of flying, but it shows that people are willing to take a chance on their system.”

The openness to new ideas is typical of the cosmonauts now flying missions to the space station. “The earlier guys were a bit reserved or uncomfortable with us,” NASA’s Lopez-Alegria says. “We had been their cold war enemies.” Today’s cosmonauts are not only completely at home with international crewmates, they are also, thanks to Facebook and other social media, far more connected with the outside world. GCTC cosmonaut Max Suraev blogged his Expedition 21 stay on the station in 2009 and 2010, posing for pictures with a “ray gun” and joking about subjects from space food to his inability to choose clothing. In many of his posts, he was more candid than the typical NASA astronaut.

One of the middle-generation cosmonauts, Yuri Malenchenko, arrived in Star City in the late 1980s as a 26-year-old fighter pilot. He went on to serve a four-month tour on Mir in 1994, flew a short shuttle mission to the International Space Station in 2000, then participated in two long-duration missions in 2003 and 2007. Now 49 and training for a third ISS stay, he is philosophical about the ways the life of a Russian cosmonaut has changed over the course of his career: “Twenty-two years ago the country was different. Since then there have been many events that happened in politics and the economy. So now Star City is different, and we are different.”

Michael Cassutt is a novelist and television writer in Studio City, California.