The Shuttle Mission No One Wants

If STS-400 launches, be prepared for one of the most dramatic spaceflights ever.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/two-shuttles-on-pad.jpg)

In a move that seems straight out of Hollywood, NASA has readied two space shuttles at the same time so that one can serve as the other’s lifeboat should trouble develop during this week's service call to the Hubble Space Telescope.

Not since July 2001, when NASA was launching missions at a quicker pace, have shuttles occupied both launch pads at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center simultaneously. While Atlantis, whose seven astronauts will service Hubble for the fourth and final time, is scheduled to launch from pad 39A today [Update: Launch is set for 2:01 p.m. Eastern time on May 11, 2009), an empty Endeavour waits on 39B for the call NASA hopes never comes. In the unlikely event that Atlantis is too damaged to return home safely—Columbia and its crew were lost during entry in 2003 due to a hole in the orbiter’s wing—Endeavour’s four astronauts would rendezvous with the crippled vehicle in orbit and rescue its crew of seven.

“This is not a flight that we think will ever fly, but the program requires that we have a capability to rescue that crew,” says Kyle Herring, a spokesman at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. If Endeavour is not needed for the rescue, it will be moved to pad 39A for its scheduled November 7 launch to resupply the International Space Station.

The rescue mission—officially designated STS-400—would happen only if in-orbit inspection of Atlantis shows that the vehicle can’t make it home safely. Even then, the rescue attempt would come only after the Atlantis crew finishes its work at Hubble, which involves five spacewalks to replace and upgrade hardware. On that STS-125 crew are commander Scott Altman, pilot Gregory Johnson, and mission specialists Andrew Feustel, Michael Good, John Grunsfeld, Mike Massimino, and Megan McArthur. Three of the astronauts—Altman, Johnson, and McArthur, the robot arm operator—have never done a spacewalk. But the entire crew has trained for the emergency rescue, which would require them to put on a spacesuit, go outside, and move to the other vehicle.

NASA has had a “launch on need” rescue capability for shuttle missions since the Columbia disaster, and the agency will continue the policy of having this arrangement as long as the shuttles keep flying. But until now, all post-Columbia missions have been to the space station, where a stranded crew could stay for up to three months—plenty of time for NASA to send another shuttle to dock with the station and bring them home. Atlantis, on the other hand, is going nowhere near the station. And without that safe haven, its crew would have power and oxygen for only about 25 days in orbit should something go wrong. Hence the need to have Endeavour primed and ready to launch.

If STS-400 were to happen, here’s how the shuttle-to-shuttle rendezvous and transfer of astronauts would go:

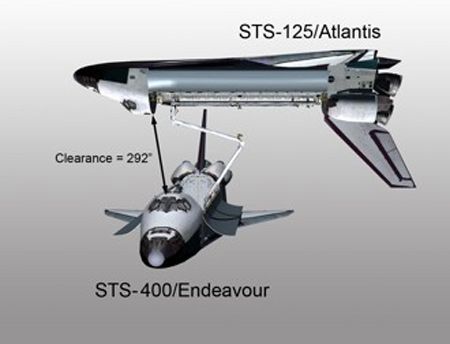

The rescue begins with the launch of Endeavour and four astronauts. About 23 hours into the flight, after rendezvousing with the stranded shuttle in orbit, Endeavour’s 50-foot-long robotic arm is used to grapple a fixture on the forward, right side of Atlantis’ cargo bay, near the airlock. At this point, the shuttles are perpendicular to each other, about 35 feet apart.

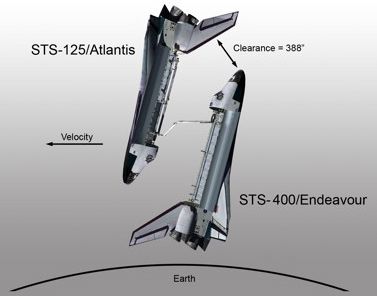

Endeavour’s arm then rotates 90 degrees, pulling the vehicles parallel in a nose-to-tail position, and about three feet closer together. From now on, Atlantis’ crew does most of the work. On the third day of the rescue mission, spacewalkers Grunsfeld and Feustel string a rope made of Kevlar along the length of the robot arm, then help McArthur follow the rope over to Endeavour, a process expected to last four hours, 50 minutes.

The next day, Grunsfeld heads back to Atlantis and helps Massimino and Johnson, the pilot, move over to Endeavour, a process that is planned to take just under two hours. Grunsfeld and Johnson stay on Endeavour, while Massimino heads back to Atlantis to retrieve Good and Altman, the commander, who by now has programmed the shuttle’s computer systems so that it can be commanded from the ground. The final spacewalk is expected to last about two and a half hours.

With all seven members of Atlantis’ crew safely on board, Endeavour’s pilot releases the grapple fixture. Ground controllers remotely close the payload bay doors on Atlantis and command its deorbit rockets to fire, sending the shuttle to a fiery re-entry over the Pacific.

The next day, flight day five, the Atlantis crew uses Endeavour’s robot arm to check the condition of the rescue vehicle’s thermal protection system to ensure a safe reentry. The shuttle comes home on the eighth day of the mission, with Atlantis’ crew seated in the (now crowded) middeck.

“The rescue is well planned, and it’s something that can be done,” says NASA spokesman James Hartsfield. “But we think the other safety precautions we have in place will preclude us from ever having to do it.”

Veteran spacewalker Greg Harbaugh, who served on a National Academy of Sciences panel that studied the risks and rewards of another Hubble servicing mission, also is confident the rescue could succeed. “I have absolute faith they can do this,” says Harbaugh, who left NASA in 2001 after 23 years and now heads the Sigma Chi Foundation in Evanston, Illinois. “I’d volunteer to fly that mission if they’d let me.”

Harbaugh says he was “an early and staunch advocate” of having astronauts work on Hubble one last time. Trying to do the job with robots, as former NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe proposed, “would be ludicrous,” Harbaugh says, and the National Academy of Sciences agreed. “I’m very grateful to see this [Hubble servicing] mission come off. It was very uncertain for a long period of time, and it took a lot of hard work and arm wrestling to pull it off.”

Of course, should STS-400 be called into action, the effect on NASA would be dramatic, he says. “Whether it’s the loss of both crews or the loss of one shuttle, that’s the end of the shuttle. That’s the last time the shuttle flies.”