Then & Now: Mars Travel Guide

Then & Now: Mars Travel Guide

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Space_TandN_Main_JJ09.jpg)

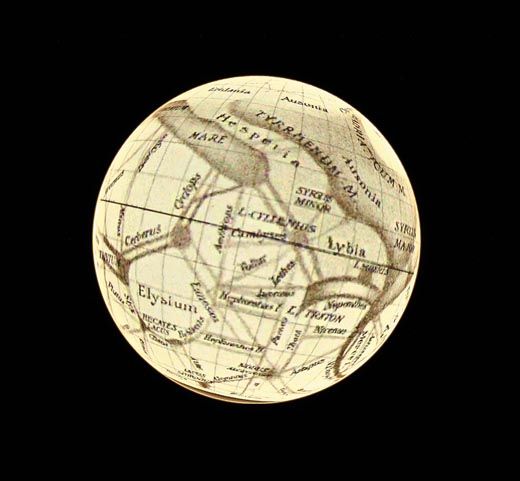

Peering through a telescope on the roof of Milan’s Brera palace in 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli sketched the first detailed map of Mars. He dutifully named its “seas” and “continents” but then insisted that what looked to him like lines on the surface must be artificial canali or “channels” (translated into English as “canals”). It was a mistake that astronomers would try for decades to validate in hopes of finding intelligent life on Mars.

It didn’t help that Schiaparelli was nearsighted and colorblind, or that he couldn’t make out much due to the limitations of his 8.6-inch-diameter telescope and the blurring effects of Mars’ wispy atmosphere (scientists now believe what he saw were probably dust streaks or sand dunes). All telescopes present an inverted image; Schiaparelli, following the conventions of his time, mapped the southern hemisphere where the northern is.

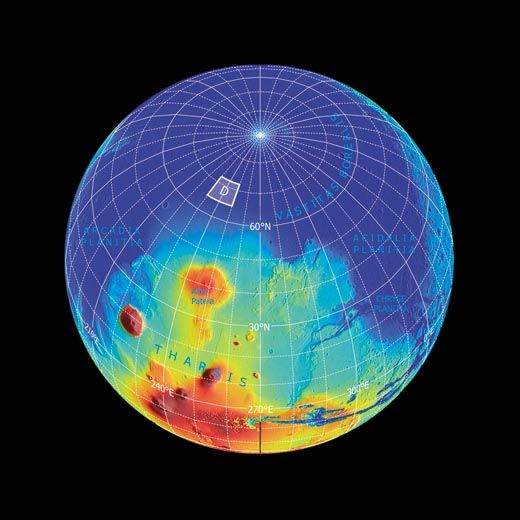

Astronomers today have the advantage of sophisticated spacecraft with near-perfect eyesight and instruments to map the planet in fine detail. Starting with Mariner 9 in 1971, a succession of orbiters, landers, and rovers have taken readings of Mars in a variety of ways and wavelengths. The planet has been mapped for elevation, daytime and nighttime temperatures, surface minerals and elements, magnetic fields, and gravity. Cameras from orbit have been able to discern features as small as seven inches (compared to 20 inches for the best commercial satellite images of Earth).

All the Mars images—along with historic maps—can be seen in a new mapping tool on Google (http://earth.google.com/mars). Released in mid-March, the tool allows users to “fly” over a 3D view of Mars, and explore its imagery and terrain. “All the data is public domain; we cooked it and stuck it in there,” says Noel Gorelick, a former Arizona State University Mars researcher who now runs the Google feature.

A history buff, Gorelick has mixed feelings about Schiaparelli’s map. “It got lots of people interested in Mars, which is a good thing, but he set Mars cartography back 50 years because people were trying to verify these canals. He drew them in a way that could only be interpreted as artificial.”

Scientists at NASA’s Ames Research Center and at ASU, which has built several Mars cameras, helped Gorelick compile images of the planet from past and present spacecraft, including Global Surveyor, Express, Observer, Odyssey, Pathfinder, Phoenix, Reconnaissance, and Viking.

“We’re almost done with the global map,” says ASU’s Phil Christensen, project manager for a thermal emissions camera aboard the Odyssey orbiter. “We’ve taken just about all the wavelengths and sensors and flown them to Mars.”

What’s left, he says, might be a mission with a synthetic radar imager to map the roughness of the terrain. Such a radar, which can penetrate a few feet beneath the surface, has been used on the space shuttle to map Earth’s terrain. Turning the tool on Mars would perhaps fill in the missing pieces of a puzzle Schiaparelli left the world more than a century ago.

Paul Hoversten is the executive editor of Air & Space.