Where the Sun Does Shine

Will space solar power ever be practical?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/solar-sats-631.jpg)

We want to believe. The latest report on a 40-year-old concept—satellites that could gather energy from the sun and supply it to the world as electricity—makes the technology seem reachable and even, eventually, affordable.

Here’s the plan: Construct in Earth orbit, where the sun never sets, gigantic collectors (a 1979 proposal envisioned arrays six miles by three miles) that would beam solar energy to similarly huge receivers on Earth, which would convert it to electricity. In other words, hook the sun up to the grid.

Here’s why it stalled the first time: According to a 1981 estimate by the National Research Council, it would have cost $3 trillion. Building and launching the enormous structures turned out to be so famously expensive that even today, advocates of space solar power struggle to overcome its reputation for outlandishness. Thirty years later, though, the idea is getting another look, for two reasons. Advances in almost all of the required technologies could dramatically reduce the size and cost of the system. And, maybe more importantly, circumstances on the planet—the cost of energy, the global impact of producing it, and worry about its supply—have grown even more critical than they were in 1979, when a newly created U.S. Department of Energy joined NASA to study the idea. This time, government interest goes beyond those two agencies—the most recent report on the feasibility of sunsats, completed last October, was requested by the Department of Defense, through a little-known group of policy advisors called the National Security Space Office.

Why them? For one thing, supplying electricity to forward bases in Iraq and Afghanistan is hugely expensive—more than a dollar a kilowatt-hour. (The average cost Stateside last year was under nine cents a kilowatt-hour.) If some organization could deliver between five and 50 megawatts for less than a dollar a kilowatt-hour, the National Security Space Office says, the Pentagon could be an anchor customer.

That’s just the kind of guaranteed business a space power system would need to become viable, according to experts involved in the study. At a press conference last October, the National Space Society, one of several space advocacy groups whose members contributed to the report, announced a new coalition to promote space solar power: the Space Solar Alliance for Future Energy. The organization hopes to convince policymakers that space power deserves government funding—at least to build a demonstrator—because of its potential to produce electricity cleanly, in vast amounts.

If the government could provide seed money, says John Mankins, “there are lots of companies around the world” that could manufacture the components of a system much smaller and smarter than the behemoth envisioned in the 1970s. Mankins, the president of the Space Power Association, is one of the world’s leading experts on the concept. Formerly a research-and-technology manager in NASA’s space exploration office, he ran several space solar power studies between 1995 and 2003 that took stock of current capabilities and calculated the investment required to get to a working system.

Five years later, advances in several technologies, starting with photovoltaics, have made him hopeful. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is now funding research with the goal of demonstrating a solar cell that can convert 50 percent of the sunlight striking it to electricity. Under the DARPA program, a consortium led by the DuPont corporation and the University of Delaware has achieved 42.8 percent efficiency by using a “rainbow” technique to separate sunlight into its constituent wavelengths and guide them to photovoltaic materials sensitive to those ranges of energies.

The sunsat studies of the 1970s assumed efficiency of nine or 10 percent, says Mankins. If that could be brought to 50 percent, the total area of the space-based solar collectors could be reduced by 80 percent while still producing the same amount of power. In addition, says Mankins, “all the power cabling, all the thermal management and attitude control, the gyros—all of the stuff that went with the 80 percent you just got rid of—it goes away.”

Wireless power transmission, the means by which the collected solar energy is delivered to the ground, has also progressed. Even 30 years ago, the basic technique was known to work. In fact, the distance record for microwave beaming was set in 1975 at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Goldstone facility near Barstow, California. Experimenters transmitted 34 kilowatts of power to a receiver almost a mile away, and more than 82 percent of it was converted to electricity. In 1993, researchers from Kobe University in Japan and Texas A&M University used a transmitter and receiver launched on a sounding rocket to demonstrate microwave transmission in space for the first time.

Techniques for building sunsats have not come as far. The 1979 study envisioned hundreds of astronaut spacewalkers toiling for decades. Robotic assembly would be more practical. But despite the sometimes photogenic robots creeping around NASA centers and university laboratories, the only construction project in space, the International Space Station, is still being assembled by astronauts.

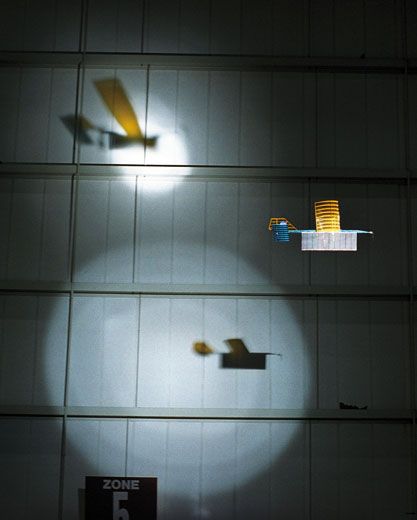

Not that the field of space robotics isn’t advancing. Robots that may someday build large structures in orbit might look like Roby Space Junior, a spiderbot created by an institute at the Vienna University of Technology (famous in Europe for creating a tiny robot soccer team). The four-inch-square Roby was designed to crawl on a vast web-like structure called a Furoshiki spacecraft, a lightweight mesh that could form the platform for large antennas, sails—or solar collectors. In 2006, the European and Japanese space agencies joined forces to launch a 65- by 130-foot Furoshiki web and three spiderbots on a sounding rocket that produced a few minutes of weightlessness. The net deployed, and the robots crawled on it for a few seconds.

The experiment seems typical of recent work on space solar power: ingenious, but a long way from tackling the huge challenges that space power systems face. The Japanese and European space agencies are funding research, but as of today, there is no credible project to build systems that will demonstrate all the necessary elements working together.

If he had the $850 million annual budget he once managed at NASA, Mankins would spend a big chunk of it to develop modular systems, a building-block approach to the assembly of large space structures. He likens it to lots of small, networked computers replacing a few big, powerful supercomputers. “If you think of trying to build a single mainframe with 1960s technology that had the processing capabilities of the Internet, it would be the size of Manhattan. But think of the Internet: You have these millions of individual computers working cooperatively over a network.”

The “modular” in modular systems represents tens of thousands of identical, mass-produced (and therefore cheap) parts. Each part, because of advances in solid-state electronics, could serve as both collector and transmitter. “Think of an Iridium satellite,” says Mankins. The Iridium network uses 66 satellites to provide wireless communication worldwide. “It has integrated into [a satellite] the size of a VW Bug power generation, intelligence, attitude control, and microwave phased arrays.” Now imagine that satellite flattened into a tiny hexagon, one of 10,000 collecting-transmitting hexagons on a single satellite.

That’s the kind of innovation Mankins wants to see funded. But to which federal agency should he apply? Neither NASA nor the Department of Energy has ever shown much interest in nurturing sunsat technology.

If the government put money into space solar power, would taxpayers get a return on their investment? Molly Macauley, an economist with Resources for the Future, a Washington, D.C. energy and environment think tank, has studied the ability of sunsats to compete with other renewable energy technologies. It’s a hard case to make, she says. “Advocates of space solar power fail to acknowledge that technological change and innovation are happening in other types of renewable energy—ground-based solar power, concentrated solar power, wind, geothermal energy. The ability to compete on a cents-per-kilowatt-hour basis is going to get more difficult, not less difficult.”

Perhaps the biggest hurdle facing space solar power is public concern about how low-level microwave beams will affect animals and humans. Never mind that the fear remains unfounded. Because of the widespread use of microwaves for communication, the Federal Communications Commission has established a safety standard for human exposure. In all proposed space power systems, the expected power density at the edges of the receiving antenna, where people are most likely to be affected, meets the standard. But explaining this to the public, which hears “microwave” and thinks “oven,” might require a large and costly education campaign. Another worry, that microwave beams could scramble a passing airliner’s avionics or harm passengers, could be addressed by restricting the airspace around the beams, just as the Federal Aviation Administration restricts the airspace over nuclear power plants. Space power advocates may find it instructive to study the political struggles of the nuclear power industry.

At the October press conference, speakers pointed out that the inevitable pursuit of higher standards of living will increase competition for energy, and that by mid-century, the global population will have increased from six to nine billion. It’s not much of a reach to apocalyptic visions of clashes over diminishing fuel.

Can the sunsat believers make the case that space solar power is one way to help meet the growing demand for clean, inexhaustible energy? And if so, will they find a branch of the government that can support and coordinate the necessary research? We want to believe.