A New Gallery Celebrates the Pioneers of Flight

In flight’s first decade, the challenges—and the possibilities—were endless.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/c5/06c5166e-b2ca-4bba-99e0-eb381a1a9d5c/15a_dj2022_gallerypreview-renderingearlyflighta59_live.jpg)

In the spring of 1909, vintners and city officials in the city of Reims in the Champagne region of France began planning an event for August of that year that would be called Le Grande Semaine D’Aviation de la Champagne (The Champagne Region’s Great Aviation Week). Just the year before, Wilbur Wright had dazzled the French aeronautical community and fueled a growing enthusiasm for the airplane. At Reims, 400,000 people gathered, and the event electrified its audience. Reims marked the introduction of the airplane to the world. It was the first time many people, especially those in government and the military, would see more than one airplane in the air at a time.

A new gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum will invite visitors to imagine that era when airplanes first took to the sky and to learn about all the exciting work that followed. The Early Flight gallery will explore how the idea of flight progressed from an ancient dream to reality and how, in just over a decade, the airplane developed into a technology that would shape the future.

Although the aerial age began with the Wright brothers, humans dreamed for millennia of flying like the birds. This dream is the starting point for the new gallery. In religion, mythology, and literature, flight appears as an almost universal symbol of the human desire to rise above the ordinary. Kites invented in China were the earliest man-made flying machines—and among the oldest artifacts in the Museum’s collection. In the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci became the first to seriously study flying machines, and a model of one of his designs will hang in the entrance to the new gallery. But not until the 19th-century revolution in science and technology did the problem of flight seem solvable. Sir George Cayley (1773–1857), considered the first aeronautical engineer, was the first to imagine a flying machine as a fixed-wing craft with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control.

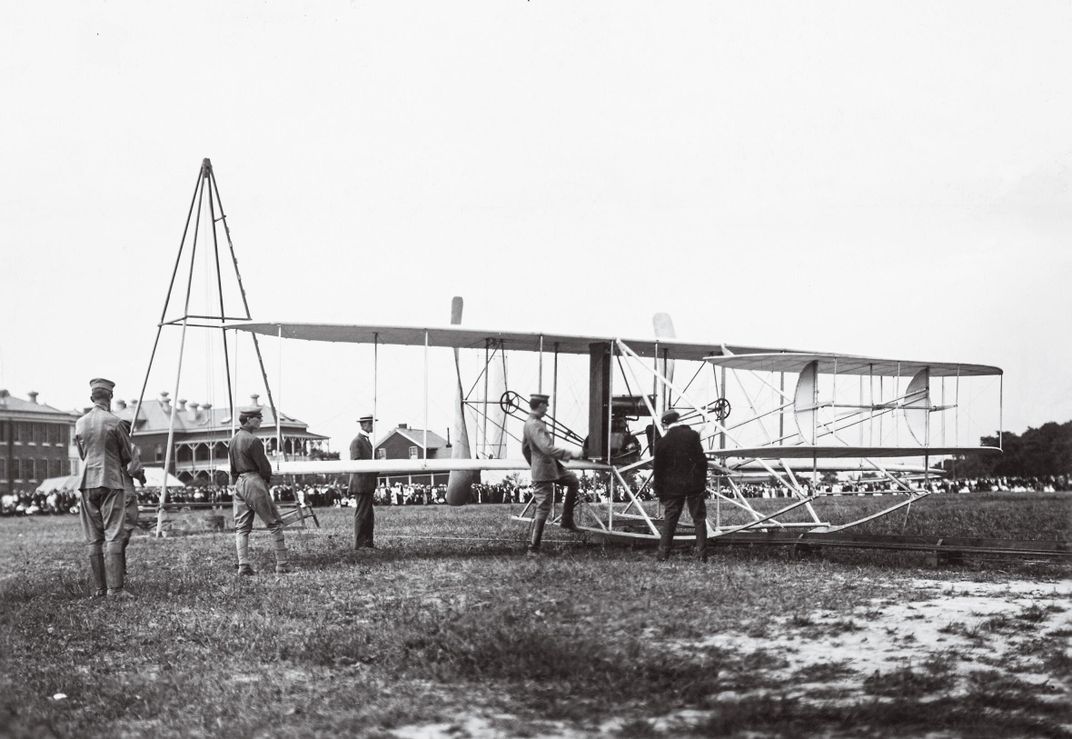

Another gallery in the Museum—The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Aerial Age—celebrates the first airplane that flew on December 17, 1903, but the Wrights’ other designs are a major focus of the Early Flight gallery. Models of Wright aircraft from their gliders and the first practical airplane they flew in 1905 to aircraft produced just before the outbreak of World War I show the progression of their work. The centerpiece of the Early Flight gallery is the 1909 Wright Military Flyer. It was donated shortly after its use by the Army and is the most original of the three Wright aircraft in the national collection. When Early Flight opens in 2022, for the first time, the Military Flyer will be displayed on the floor where visitors can get a really good look at the world’s first military aircraft.

At the historic 1909 Reims event, the money was on Louis Blériot to win the Gordon Bennett cup for the fastest time over the course. After all, the month before, he had become the first pilot to cross the English Channel. But Glenn Curtiss, the sole American competitor, staged an upset. In Early Flight, his Curtiss D-III aircraft—a later design favored by many early aviators—will highlight his successful aviation career. The type that Blériot flew across the Channel and again at Reims is also on display. Built in 1914, this particular Blériot XI was flown by John “upside down” Domenjoz, his nickname the result of his showmanship: He was famous for flying loops. Appropriately, the aircraft will be suspended upside down in the new gallery, allowing visitors to examine a reproduction of the special leather safety harness he used to hold himself in. (The original is in the collection but is too fragile to hang in the aircraft.)

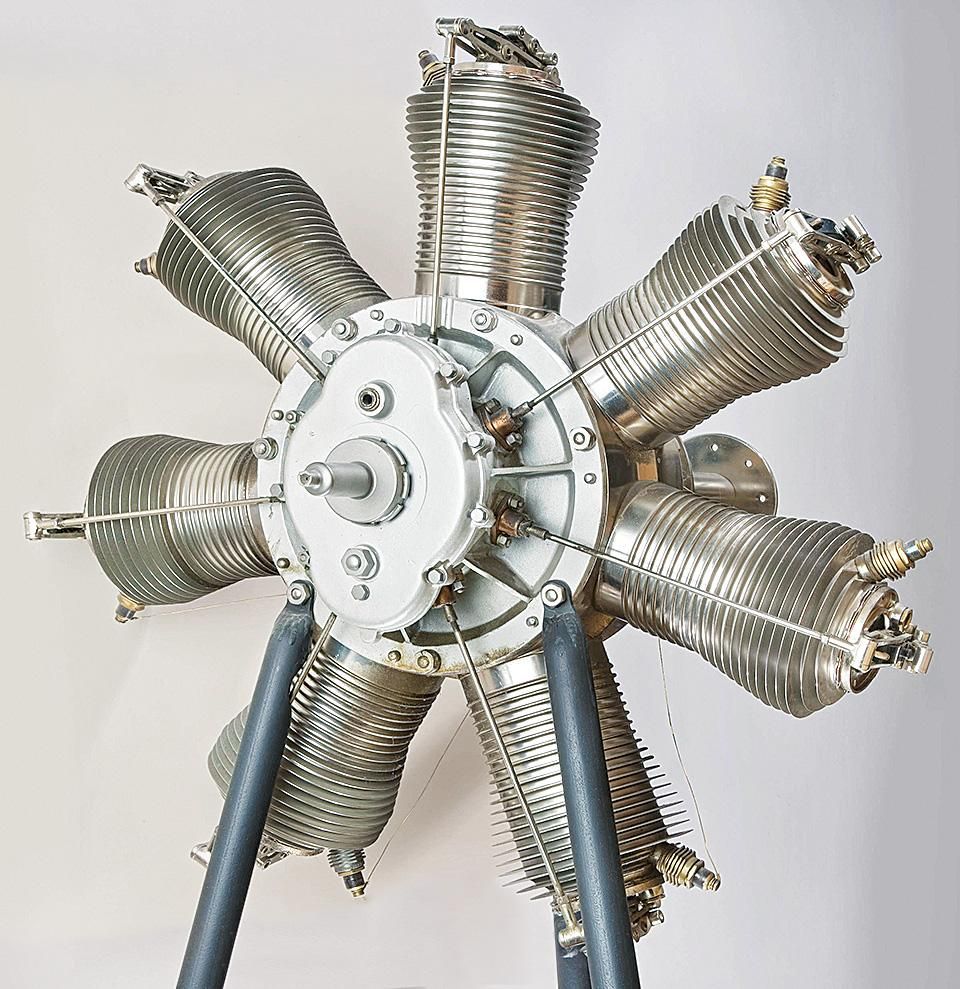

To help visitors understand the technical problems faced by early inventors and the creative solutions they found, the Museum is installing several interactive displays. One will show the inner workings of a rotary engine and compare it to the more familiar radial engine, which it outwardly resembles. Among the more challenging problems in early flight was finding a suitable engine to power an aircraft. Early types were limited in the amount of weight they could lift into the air, so a light, powerful motor was a necessity. Many early experimenters designed and built the engine themselves, but soon manufacturers took note of the demand and an infant aero engine industry began to emerge.

The new gallery has an impressive selection of extremely rare aero engines. Starting with the diminutive Stringfellow steam engine—considered the oldest aero engine in existence—the gallery includes a Clement V-2 from Alberto Santos-Dumont’s No. 9 airship. It is the smallest motor ever used to power a dirigible. Santos-Dumont, a wealthy Brazilian based in Paris, is one of aviation’s earliest celebrities. He first became famous by flying an earlier dirigible—No. 6—around the Eiffel Tower in 1901. Dumont is also credited with the first airplane flight in Europe, made in 1906.

Another educational interactive is a flight simulator that offers visitors the chance to experience the types of flight controls that early aviators experimented with. There was no one obvious arrangement of controls, and there were nearly as many ways for the pilot to control these flight surfaces as there were designers. This interactive simulates each of the three major types of control systems, illustrating both the cockpit controls and the control surfaces on the aircraft.

The first generation of aviators was made up of a surprising variety of people of different ages, origins, races, and genders. An interactive database of pilots from around the world shows just how varied the early aviators were. Digital scrapbooks aimed at younger visitors will give insight into the backgrounds and achievements of Harriet Quimby, Katherine Wright, and Alberto Santos-Dumont and their influence on early aviation.

From the invention of the airplane in 1903 to the beginning of World War I, men and women in America and around the world were pushing the boundaries of this new phenomenon, setting records, and participating in airshows. This first period of the aerial age lasted only slightly longer than 10 years, but almost all that followed in aviation has been based on the inventions of that first magical decade.

Christopher Moore is a museum specialist at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum aeronautics department and lead curator for the Early Flight gallery.

EARLY FLIGHT IS MADE POSSIBLE THROUGH THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF GLENN AND DONNA BOUTILIER AND RICHARD W. MCKINNEY.